Wednesday, September 5th, 2012

Titian’s “Monkey Laocoön”

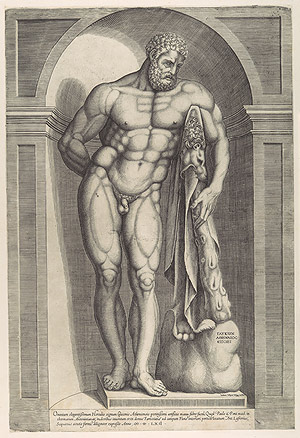

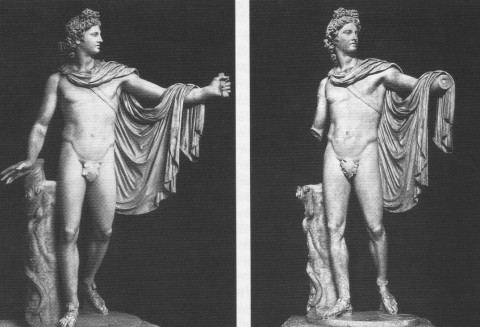

I am endlessly intrigued by how Renaissance and Baroque artists were influenced by the Laocoön (1st century BC), a Hellenistic sculpture which was excavated in January 1506. In fact, I think that Renaissance and Baroque art would be quite different if this sculpture was never unearthed. Scholarship on Baroque art (and the acceptance of Baroque art as a subject of study) would be different, too.

But perhaps not all Renaissance and Baroque artists were infatuated with the Laocoön, as might be suggested in Titian’s satire of the statue, Monkey Laocoön (c. 1545). Thanks to Niccolo Boldrini, who did an engraving based off of Titian’s pen drawing, one can perhaps deduce Titian’s sentiment. As early as the 17th century, scholars proposed think that Titian created this drawing to mock contemporary idolaters of this ancient statue.1

However, there are a lot of other debates as to why Titian might have created this drawing. As early as 1831, it was proposed that Titian’s drawing was supposed to be a satire on Bandinelli’s clumsy copy of the sculpture.2 Alternatively, Oskar Fischel proposed in 1917 that Titian created this drawing to free himself from the overwhelming influence that the statue had upon his work.3

I think that Fischel’s theory also is interesting, since it is known that Titian owned a cast of the Laocoön.4 Seymour Howard even notes that the “poses and pathos” of the Laocoön appear in Titian’s Averoldi altarpiece in Brescia (shown above), which was made about twenty years before Titian’s caricature drawing. Titian even expressed admiration for classical sculptures in a letter (which pre-dates the woodcut), writing that while in Rome he was “learning from these most wonderful ancient stones.”5

Perhaps all of these arguments can co-exist. Titian might have been criticizing the contemporary infatuation with this sculpture, but also laughing at himself and his own reliance on antiquity. (I bet Titian had a sense of humor!) Or, who knows, perhaps this caricature is simply the product of boredom and doodling?

I also wanted to mention one more argument about this caricature, which is completely different from anything else that has been put forward. Janson argued that Titian’s drawing serves as a commentary on contemporary debates (between theorists Vesalius and Galen) about similarities between ape and human anatomy. Janson feels like Titian was critical of Galen, and interprets the caricature as stating, “This is what the heroic bodies of classical antiquity would have to look like in order to conform to the anatomical specifications of Galen!”6

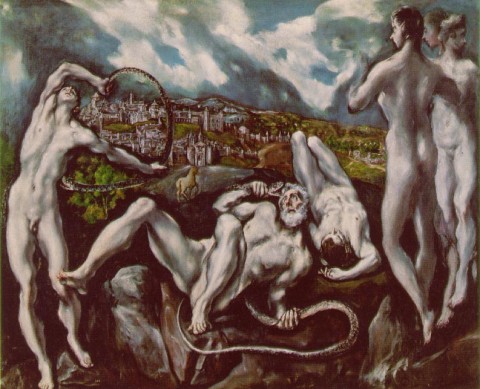

Is there any theory that is convincing to you? I like aspects of each one, for different reasons. Do you know of any other satires associated with the Laocoön? One more thought: Now that I’m familiar with Titian’s Monkey Laocoön, I think that I will forever look at El Greco’s Laocoön painting (early 1610s, shown above) in a different light. Doesn’t it look like the Trojan priest has sprouted a tail? Oh dear!

1 Philip Sohm, “Fighting with Style” in Italian Baroque Artby Susan M. Dixon, ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 39, 45. To see more information on the mention of this theory in the seventeenth-century, see footnote #8 in H. W. Janson, “Titian’s Laocoön Caricature and the Vesalian-Galenist Controversy” in The Art Bulletin 28, no. 1 (1946): 49.

2 Janson, 49. This argument makes me wonder if Titian might have agreed or disagreed with Michelangelo’s interpretation that the Laocoön originally was depicted with a bent arm. Bandinelli proposed that the central figure was depicted with an extended right arm. However, Titian’s drawing depicts a bent arm, which seems more reminiscent of Michelangelo’s interpretation (and is consistent with the modern restoration, after the arm was discovered in the early 20th century. To read more about the Michelangelo and Bandinelli debate, see here: https://albertis-window.com/2011/04/the-laocoon-bandinelli-vs-michelangelo/

3 Ibid. Janson also critiques Fischel’s theory, finding that Titian would not have created such a personal response in a drawing that was intended for mass distribution in the form of a woodcut. See Janson, p. 50. As far as I can tell, though, we don’t know for certain if this drawing originally was intended to be made into a woodcut.

4 Seymour Howard, “On Iconology, Intention, Imagos, and Myths of Meaning,” in Arbitus et Historiae 17, no. 34 (1996): 94.

5 Janson, p. 50.

6 Ibid., 51.