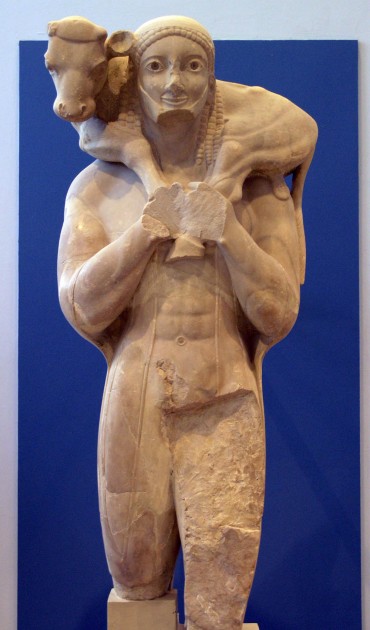

Kritios Boy, c. 480 BCE. Archaeological Museum, Athens. Image courtesy Wikipedia via user Tetrakys

When I saw the Kritios Boy on display in Athens (back in 2003, in the old version of the Acropolis Museum), I was struck by how the statue was smaller than I anticipated. I naturally assumed that the scale of the sculpture was akin to the large size of the reproductions I had seen in my editions of Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. However, this work of art, which had loomed so large in my mind as an undergraduate, is only 3’10” (1.17 m) tall.

In truth, though, the Kritios Boy’s role in art history has been anything but small. This figure dominates many canonical art history books as the forefront example of the Early Classical period (also called the Severe Style). And, in some ways, we know more about the start of the Early Classical period because of the Kritios Boy.

This sculpture is an example of “Perserschutt” (meaning “Persian debris”). This sculpture, along with several others sculptures, form part of the sculptural “debris” that resulted from when the Persians burned and sacked the Athenian acropolis in conjunction with the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE.1 Some think that head of the Kritios Boy might have been lopped off during this same time, perhaps as a way for the Persians to symbolically express their anger toward and desired conquest over the Greeks.2 Another theory is that this head was intentionally decapitated by an Athenian, perhaps for something as elevated as a religious sacrifice, or something as mundane as prepping the sculpture to be packing material for the acropolis.3

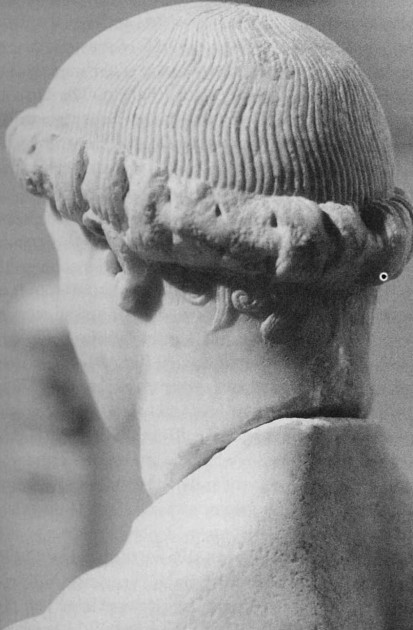

Kritios Boy, back of the head, c. 480 BCE

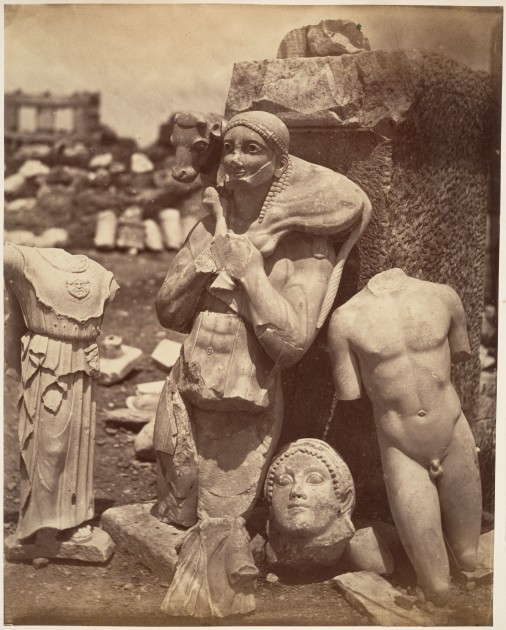

At some point after the sack of the acropolis, the Greeks took the damaged sculptural rubble, including the Kritios Boy and other sculptures, and buried it in pits underneath surface of the religious complex. The placement of this Perserschutt may have happened as soon as 479 BCE, or it could have taken place incrementally until the rebuilding of the acropolis by Pericles in c. 447-432 BCE. Regardless, the Kritios Boy was hidden from the world for well over two thousand years, and it finally was unearthed long after art history was established as a discipline. The body of the Kritios Boy was discovered in 1865, although its decapitated head was not discovered until 1888.2

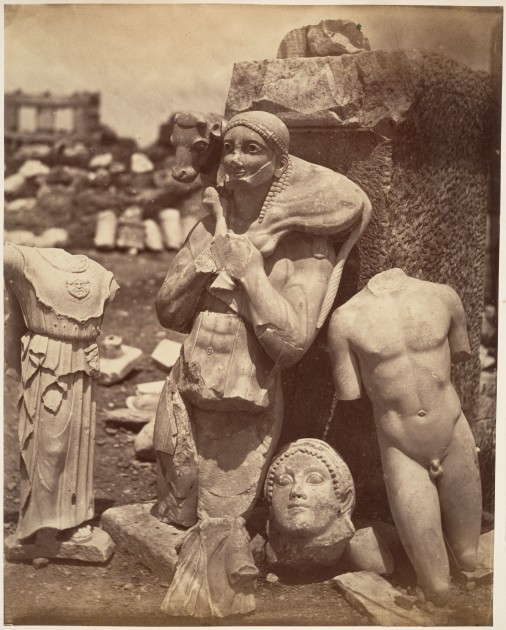

The Calf-Bearer and the Kritios Boy Shortly After Exhumation on the Acropolis, with the Danseuse du Temple de Bacchus, ca. 1865. Albumen silver print from glass negative. Public domain image courtesy http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283139

As a result, it would be easy to assume that we pretty specific date for the Kritios Boy: it is possible that this sculpture was made before 480 BCE, which is when the Persians sacked the acropolis. This is based on the assumption that the Perserschutt is a homogeneous deposit of items made on or before 480 BCE. However, not everyone agrees with this date or theory, though. Here are two arguments regarding the dating of the Kritios Boy, and the ramifications of adopting either argument:

1) Argument that the Kritios Boy was made on or before 480 BCE:

One of the assumptions that the Kritios Boy was made before Persian attacks is that the body was found with other works of art in the Archaic style. If this is the case, then the Kritios Boy was a leader in introducing the Classical Style. This can segue into a discussion of pinpointing the beginning of the Early Classical period: before the Kritios Boy was excavated in 1865, the popular starting date for the Early Classical period was 480 BC. Winckelmann’s Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (1764) pinpointed the Persian Wars of 480-479 BCE as the starting point for the Early Classical periods, since the victorious Greeks would have felt a sense of self-confidence, capability, and worth.

However, if the Kritios Boy predates 480 BCE and therefore was attacked in the Persian sack of the acropolis, this means that the shift in artistic style took place before the time that Winckelmann pinpointed. Instead, it seems more likely that the Early Classical period should be pinpointed to the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, in which the Greeks won a decisive victory over the Persians.

2) Argument that the Kritios Boy was made after 480 BCE:

Hurwit finds that the statue is not in good enough condition to have been made, broken by the Persians, and then buried with the rest of the Perserschutt, all within a matter of years. Moreover, he thinks that this sculpture may have been made, perhaps as a copy, after a bronze sculpture. The smaller scale of the statue (roughly two-thirds or three-fourths life size) is typical for bronze, and the fine attention hair strands and curly wisps on the neck suggest the plastic capabilities of the bronze medium.6 Furthermore, Hurwit points out that the hair ornament, a ring, around the Kritios Boy’s head are uncommon before 480. Furthermore, the looped curls around the hair ring only comes into fashion on and after 480 BCE.7

Hurwit finds stylistic similarities with a head of Harmodios (original Greek versions of 477-476 BCE) and suggests that the Kritios Boy may not only post-date 479 BCE, but perhaps specifically post-date this sculpture between 475-470.8

There are other nuances to this argument as well, which are discussed by Hurwit and Stewart. However, overall one can say that this post-Persian argument places the Kritios Boy not as an instigator of the Early Classical style, but within a greater continuum of (and likely as a response to) vanguard stylistic elements that appeared in other works of art. If this is the case, I wonder if textbooks should rethink the way that the Kritios Boy is introduced to art history students? One has to be careful to make stress that the Kritios Boy is indicative of these changes in style, but our loss of extant examples and a truly clear understanding of Perserschutt chronology prevent us from knowing whether the Kritios boy was an instigator or follower of the nascent Severe Style.