Nicholas Galanin, “Ism #1,” 2013. 19″ x 32″, digital photographic print. Image courtesy of the artist

At the end of last month, I heard Dr. Christopher Green give a presentation that included some works of art by Nicholas Galanin, who is a Tlingtit-Unanagax contemporary artist. I was particularly struck by the digital photographic print Ism #1, which features the famous icon of Christ from the Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. However, in Galanin’s image, the face of Jesus has been covered with a Tlingit shaman’s mask (and not an actual shaman’s mask, which the Tlingit consider personal and not for public display, but a replica of a shaman’s mask).1 By creating a digital compilation of an original Byzantine painting with a photograph of a replica of a Tlingit mask (a replica made by Don Lelooska Smith of Cherokee heritage), Galanin’s work of art is full of layers that raise attention to authenticity, originality, appropriation and even theft.2 Galanin explained Ism #1 further in a quote on the Eazel website:

“The shaman’s mask over the crucified Christ can be read as theft of Indigenous culture and experience by a non-Indigenous community. This is also a strategy to use iconography understandable to a Eurocentric culture to make clear the level of suffering endured by carriers of Indigenous culture, and to elevate the importance and significance of the shaman’s mask to this audience.”

The two represented objects refer to complicated histories of destruction and disturbance. The Mount Sinai icon is a rare example of Byzantine art from the 6th century, because it pre-dates the period of iconoclasm (icon destruction) that took place in the 8th and 9th centuries. Because this icon was located at a remote location on a peninsula near the Red Sea, it escaped iconoclastic destruction. And yet, the original Tlingit shaman’s mask, which Galanin references through a secular copy, was also in a forested location with restricted access. It was located at a Tlingit shaman’s grave (at the area called Point Lena, Alaska), but it did not escape disturbance: it was “collected” (i.e. stolen) by George Emmons in 1919. The mask was located in the National Museum of the American Indian in the last half of the 20th century, only to be repatriated in 2003.1

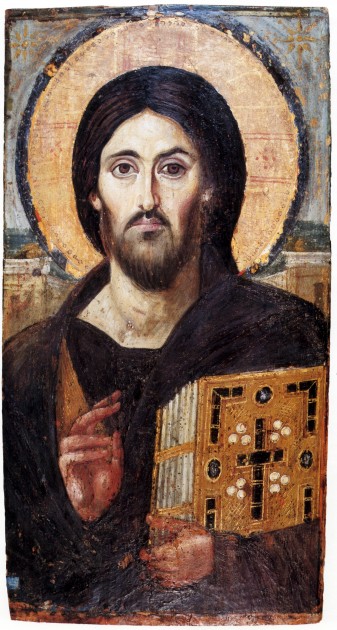

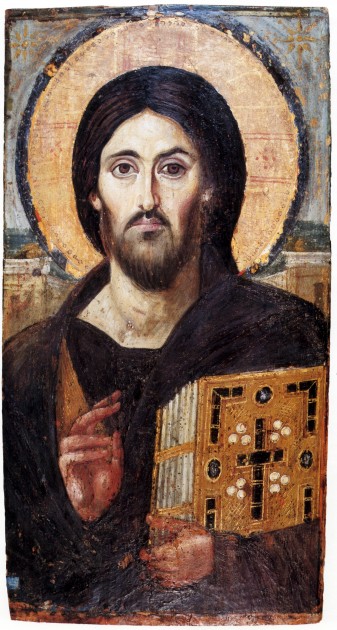

Christ, Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai, 6th century. 33.1 x 19.4 in (84 x 45.5 cm, encaustic painting (pigments and wax). Image courtesy Wikipedia

The meaning of the icon clearly has been altered by the addition of the Tlingit mask. In the original icon, Jesus’s face is asymmetrical: his right side (viewer’s left) is welcoming and calm, whereas his left side (viewer’s right) has harsher shadows and is pulled into a sneer. (If you want to see how differently the sides appear, check out these digital mockups of how the full faces would appear if the sides were symmetrical.) Through this split composition, the icon expresses the dual nature of Jesus Christ’s roles, as both a loving Savior for the righteous and a harsh Judge for the wicked.

I think that the composition of Christ’s face is also applicable to the context of the Christian missionaries interacting with Indigenous people during the period of Western expansion. Galanin explains, “During colonization and settlement, Christian missionaries functioned as a wedge used to split apart Indigenous communities.” As such, for those viewers who are familiar with this (hidden) split face, it can can serve as a reminder of Christianity’s divisive role in history. The visual layering even recalls this sense of the past, with the split face serving as the “older” first layer. I think that a hope of rectification and restitution is suggested by superimposing a symmetrical, visually-balanced mask on top of this asymmetrical face, especially with the knowledge that the original mask was repatriated to the Tlingit in 2003. And yet, by having these two cultures bound together within Galanin’s digital photomontage, the layered pull between the past and present conveys that an imbalance still exists today.

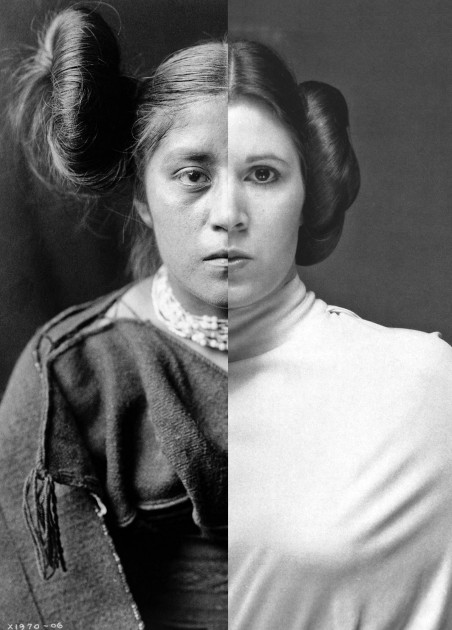

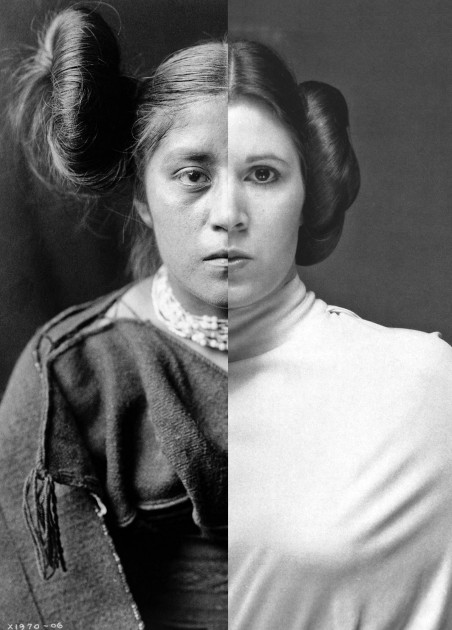

Nicholas Galanin, “Things Are Looking Native, Native’s Looking Whiter,” 2012. Giclée print, 15.5″ x 20.25″. Image courtesy of the artist

This pull between past, present, and future is also seen in Galanin’s photographic image Things Are Looking Native, Native’s Looking Whiter (shown above). The past is suggested with the photograph on the left, which comes from a photograph of a Hopi-Tewa woman that was taken in the early 20th century by Edward Curtis. The butterfly whorl hairstyle (sometimes described as “squash blossom”) was worn by unmarried Hopi women. The older photograph is juxtaposed with a promotional photograph on the right of actor Carrie Fisher as the character Princess Leia from “Star Wars.” This juxtaposition references contemporary pop culture but also hints at the past and future too, with reference to a futuristic society that lived “a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.”

Just with the photograph of Ism #1, references to destruction and disturbance are compounded in this photographic print. In the early 20th century, when the controversial artist Edward Curtis was taking his photographs, the US government was involved efforts to “westernize” Indigenous communities and establish legislation and reservation policies that would restrict Indigenous rights. These actions included setting up boarding schools that worked to eradicate traditional Indigenous cultures and languages. Edward Curtis’s work, through the sense of false authenticity conveyed through the photographic medium, supported what Galanin calls “the national fantasy that Indigenous people and ways of life were disappearing. The imagery created was often staged with props Curtis carried with him, to construct photos that would eventually be used as a standard for disappearing tradition and authenticity.” With this context of destruction and cultural disturbance in mind, a Star Wars fan can’t help but think of the destruction of Princess Leia’s home planet, Alderaan, in “Episode IV: A New Hope” due to the machinations of the Galactic Empire.

Juxtaposing these images draws attention to issues of cultural appropriation and inaccurate constructs. Galanin explains on his Flickr portfolio, “In borrowing from Indigenous aesthetics, the image projects settler claims to Indigenous culture into the future. The title speaks to consumer culture’s desire to claim ‘Native inspired’ looks, while simultaneously refusing Indigenous people the agency to define Indigenous culture in an increasingly hybrid world. I point out that while non-Native ‘things’ look Native to the non-Natives who produce them, Natives continue to be held to historical constructs of Native-ness devised by non-Natives.” The horizontal split between the images creates visual competition, which emphasizes that these historical constructs for Natives still exist today. I appreciate that the faces of the figures are aligned as closely as possible, however, since that suggests to me that Native and non-Native cultures have the potential to come together in a balanced and respectful way.

(And on a side note, First Nation K’ómox artist Andy Everson includes references to Star Wars in his work as a way to reference dichotomies in life and reflect on cultural heritage. Andy was photographed in an Imperial Stormtrooper costume, covered with formline designs, by Navajo artist Will Wilson for his ongoing photographic project Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX). You can learn more about the work of these two artists here.)

I look forward to following Nicholas Galanin’s work! His “Never Forget” installation from 2021 also caught my attention, as it raises related questions about past, present, commodification and commercialism (even a different type of reference to Hollywood!), but directly and forthrightly addresses settler land occupation.