Saturday, September 16th, 2017

The Dresden Frauenkirche and “New” Baroque Thoughts

A few weeks ago I had an amazing opportunity to travel to Germany and spend time with two dear friends. My trip began in Munich and eventually ended up in Berlin. I spent an inordinate amount of time at museums, naturally, and I thought a lot about my current aesthetic preferences while I gallivanted about the cultural centers of various German cities and towns. Many of the things I saw that I was drawn to, aesthetically, were typically not the things that I study or teach about in my classes. Perhaps my mind really wanted to feel like it was on summer vacation!

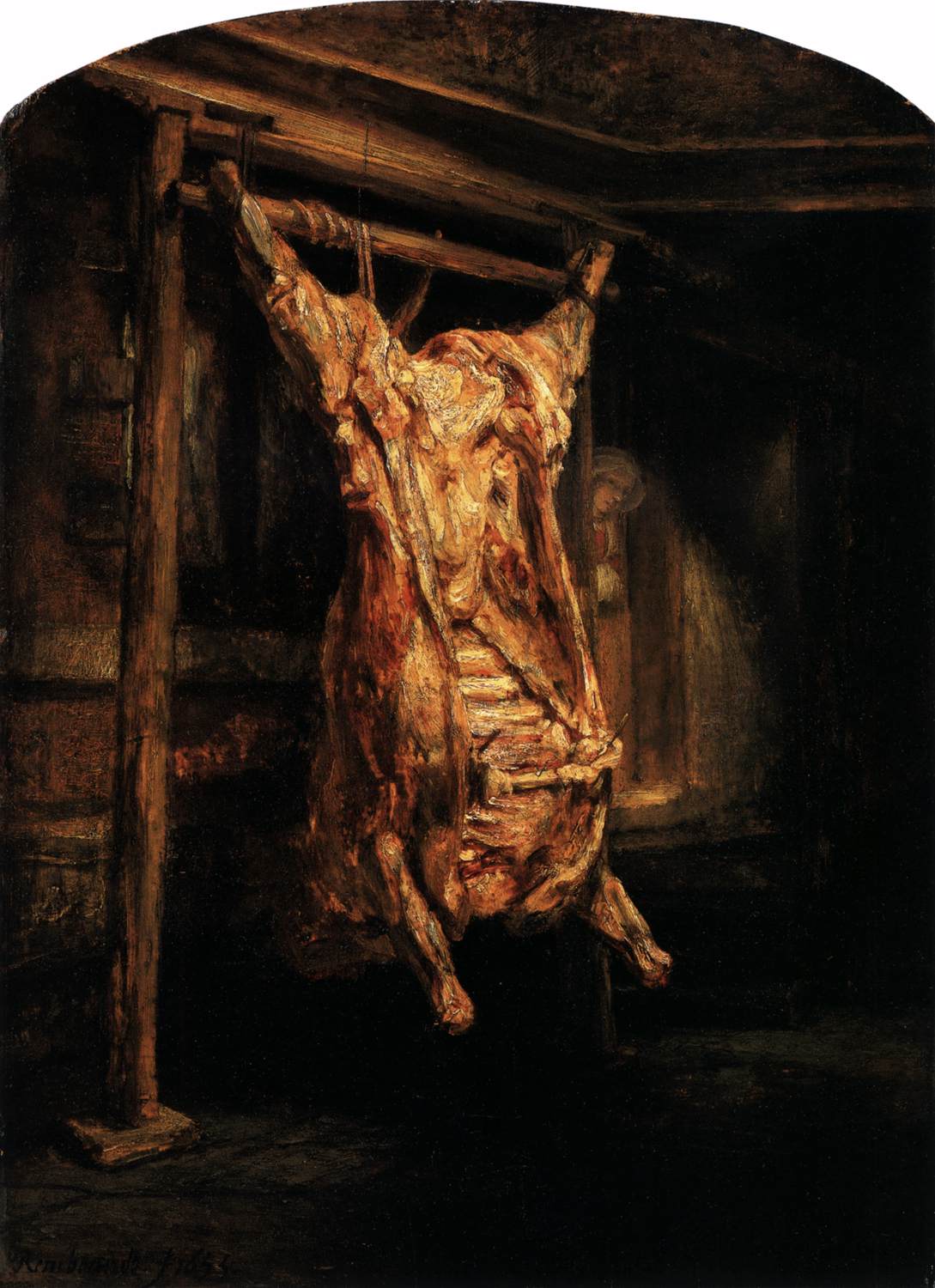

Frauenkirche, Dresden. Original structure completed 1743; restored and rebuilt structure completed 2005.

One thing that really surprised me was my aesthetic reaction to the Frauenkirche in Dresden. This building is unique because it is a virtual replica of the original building that was destroyed in the WWII bombing of Dresden in 1945. The original building was built 1726-1743. After the bombing of Dresden, the church lay in ruins for several decades (see this photo from about 1965). However, through massive fundraising efforts in the 1980s and 1990s, the church was able to be rebuilt and completed in 2005.

I loved walking around the exterior of this church, because it was a really good reminder to me of how the church is old and new. Several thousands of stones were salvaged from the old building and incorporated into the new structure. The older stones have a darker patina due to weathering and fire damage. I like how the pock-marked appearance of the cathedral gives off a sense of the structure’s complex history and interrupted sense of time, even if the precise placement of the individual stones is not completely accurate to that of the original structure.1

I’ve realized more and more that I like art that gives off some kind of a visual sense of age or time, and I’m trying to determine how much history would I prefer to be visually evident. Some 19th-century art critics considered the successive coats of varnish on a painting to be a mark of beauty and excellence, because they gave an indication of the painting’s age.2 For example, the 18th-century critic Sir George Beaumont wrote, “A good picture, like a good fiddle, should be brown.”3 I don’t know if I would completely go that far, because even while in Dresden I commented to my friend about how it was unfortunate that old structures like the Hofkirche were covered with soot and grime. But think there needs to be some good balance between a sense of the old and the new, and the polka-dotted Frauenkirche exterior helped me to feel connected to the past.

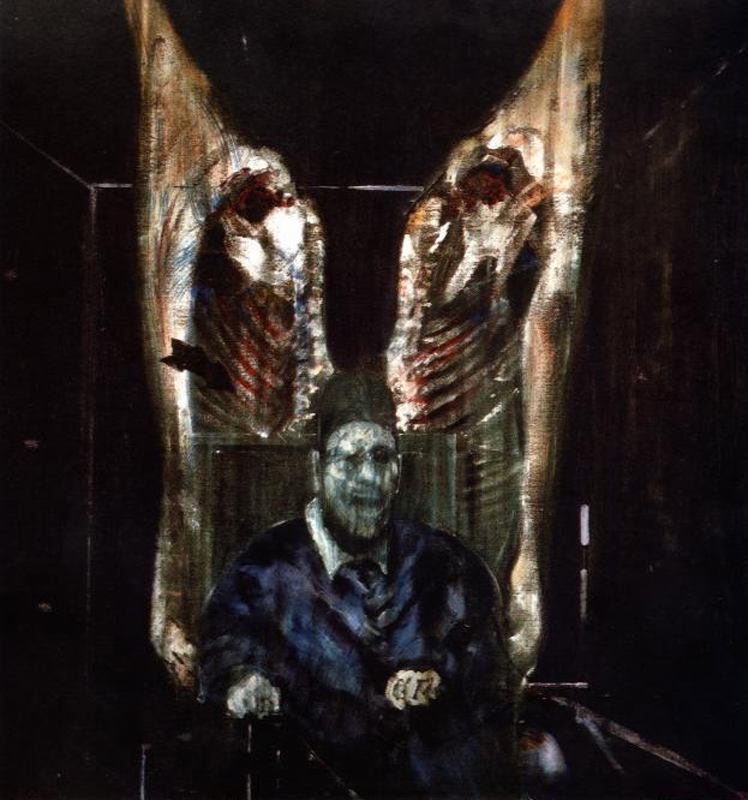

The interior of the Frauenkirche, however, was too new and fresh for me. I know that parts of the original altar were reincorporated into the new structure, but even these salvaged pieces of history were painted over, and it was hard to get a sense of age anywhere.4 The interior was so light and the colors of the paintings were so bright! It made me realize that, had I lived in the 17th or the 18th century, I might not have liked the Baroque style as much, because then it would have been new for its time. Everything in the church appeared to be so clean and recent – and I began to realize that part of the drama that is so inherently “Baroque” in my mind is connected to the mysterious, theatrical aura that these works exude today because they are old.

Interior of the Frauenkirche, Dresden. Interior is a 21st-century replica (completed 2005) of the original 18th-century structure (completed 1743). Image courtesy Wikipedia

Visiting the Frauenkirche and thinking about my aesthetic preferences for The Old reminded of a quote by Bernard Berenson, which my friend Dr. F shared with me a few months ago. Berenson points out that the inherent biases and preferences which writers bring to their discussions of works of art, and Berenson uses Goethe’s as an example:

“Some months before passing through Assisi he [Goethe] made no reference to San Francesco and all its marvelous Trecento paintings. Such a genius and yet so limited in his visual tastes, he expresses and interprets only the admirations that were current in his epoch, and accepted in the cultured world he belonged to before coming to Italy. If in following his steps I notice his indifference to what is our chief delight now, I do not by any means want to belittle the importance of his pages. I want only to point out the distance created by different cultural traditions between us and eminent men of other ages.”5

This quote makes me wonder if my “chief delight” in Baroque art is its age – something which Baroque artists didn’t inherently imbue in their works of art. I don’t think that this is inherently a bad thing, but I think it should make me reconsider why I am drawn to certain works of art. And it’s revealing to think about this in terms of my escapist personality and character: I want to connect with the past and bygone eras, simply because they are not the present. Old, vintage and antique things need to be unattainable in some way, because that is partially what makes them enjoyable to me!

1 Mark Jarzombek, “Disguised Visibilities: Dresden/’Dresden,'” in Memory and Architecture by Elena Basti ed., 56. Source available online: http://web.mit.edu/mmj4/www/downloads/disguised_vis.pdf

2 David A. Scott, Art, Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery (Los Angeles: UCLA, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press), 2016), p. 21.

3 Ibid.

4 André Harrmann, “Architectural Reconstructions: The Current Develpoment in Germany” (Master’s thesis, The University of Georgia, 2006), 56. Source available online: https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/harrmann_andre_200608_mhp.pdf

5 Bernard Berenson, The Passionate Sightseer, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1960), 124. Source available online: https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.507665/2015.507665.The-Passionate_djvu.txt