Friday, December 23rd, 2011

Female Artists and Nativity Scenes

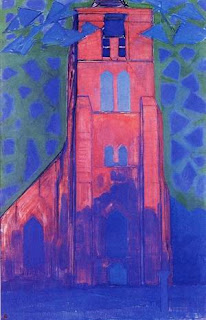

Evie Hone, detail of "Nativity," 1946. Stained glass window located at Saint Stanislaus College, Tullabeg

Keeping in line with the theme for this week on female artists (in connection with my ongoing GIVEAWAY!), I wanted to write a Christmas post on female artists who painted Nativity scenes. This was a much more frustrating project than I anticipated; it was difficult to come up with examples to share. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that there aren’t too many (extant) examples out there, but I am a little disappointed. In some ways, it seems a little ironic that the most famous artistic scenes about birth were created by men!

One of the examples that I enjoyed discovering was the Nativity window located at Saint Stanislaus College in Tullabeg, Ireland (see detail above). This window was created by the artist Evie Hone in the mid-20th century. Originally trained as a painter, Hone turned toward stained glass later in her career. S. B. Kennedy writes that this change to stained glass “gave [Hone] free rein to her growing power as a colorist.”1

There are a few contemporary nativity scenes which I think are interesting. Janet McKenzie was commissioned to create The Nativity Project. I think her painting Mary and the Midwives (2003) is quite interesting, not only in terms of style but also subject matter and composition. I also think Flor Larios’ Nativity Star (n.d.) is fun, as well as the Nativity scenes by Valerie Atkisson.

As for more historical art (pre-20th century), I have learned that most of the nativity paintings either longer exist (or are not available online). For example, a Nativity by Lucrina Fetti (17th century) was destroyed during the Napoleonic era.2 Similarly, I can’t find any location for the nativity scene that was made by Victorian artist Eleanor Vere Boyle (etched in brown ink on vellum).3 Another “untraced” painting was created by the discalced Carmelite nun, Maria Eufrasia della Croce painted a nativity scene for the church San Giuseppe a Capo al Case. The painting received quite a bit of praise. In the 17th century, Filippo de Rossi said that this painting was created by “a most excellent nun and painter of the place.”4 Even Bruzzio was able to drum up some praise for this painting, saying that “even if it is by a woman it is not a displeasing work.”5

It is disappointing that these works don’t exist anymore. However, don’t let this thought keep you from enjoying the Christmas holiday, friends! Do you know of any other nativity scenes (or “Adoration of the Shepherds” scenes) created by female artists? Please share! One of the only other examples (which is kinda-sorta similar to Christmas nativity scenes) is Artemisia Gentileschi’s Birth of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1635).

Happy holidays!

1 S. B. Kennedy, “Evie Hone,” in Dictionary of Women Artists, vol. 1 (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997), p. 402. Available online here.

2 Myriam Zerbi Fanna, “Lucrina Fetti” in Dictionary of Women Artists, vol. 1 (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997), p. 520-21. Available online here.

3 Ellen Creathorne Clayton, English Female Artists, vol. 2, p. 358.

4 Marylin Dunn, “Convents,” in Dictionary of Women Artists, vol. 1 (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997), p. 26. Available online here. See Franca Trinchieri Camiz, “Croce,” in Dictionary of Women Artists, vol. 1 (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997), p. 421. Available online here.

5 Camiz, 421.