Tuesday, July 7th, 2015

Guest Post: Artistic Depictions of Card Games between 1880 and 1980

Editor’s note: I was recently contacted by Sophie Jackson, a gaming journalist and writer. Sophie wrote an article which featured a several paintings with depictions of card games. I had never seen some of these paintings before, which so it was fun to discover them through Sophie’s article. Although I rarely feature guest posts from outsiders, I feel like this article fits well with my blog (I’m reminded of when I set out on a quest to find depictions of laundresses), and I’m happy to feature Sophie’s post here.

Artistic Depictions of Card Games between 1880 and 1980

by Sophie Jackson

From Caravaggio to Picasso, Boulogne to Cézanne, the depiction of card games in major works of art has become an increasingly popular subject of study amongst critics. Many have focused on how the controversial but enduring topic of gambling and its place in society has, as with all major social issues, been examined by artists in various ways throughout the centuries. These artworks offer us unique insight into the spread of specific games, the changing manner in which they’re played and – in the case of games such as poker – the legal history. Inspired by Francesco Esposito’s original article, this piece seeks to comment on individual artistic depictions of card games over a time period of one hundred years, starting with Gustave Caillebotte’s ‘Game of Bezique’ from 1880.

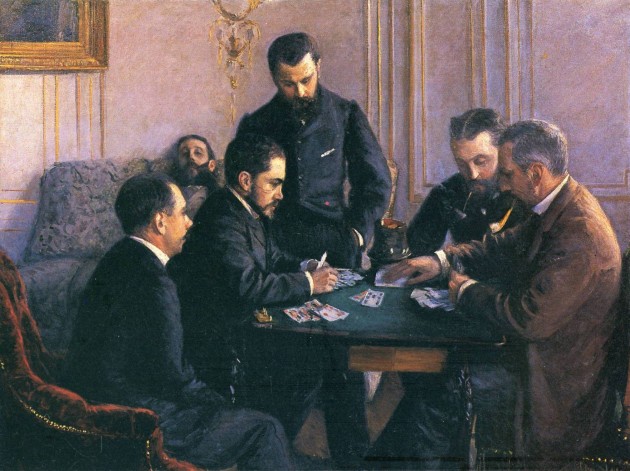

Born into a wealthy family, Caillebotte was brought up in Paris and pursued a career in painting after returning home from the Franco-Prussian war. His art typically depicted the intimate, every-day ongoings you might find in a 19th century upper-class household.1 Caillebotte’s subjects were usually engaged in some leisurely activity, whether it be piano playing, sewing or high tea. Bezique was a popular card game in Paris during the latter half of the 1800s, deriving from its earlier variant, ‘Piquet.’ In Caillebotte’s Game of Bezique, a group of men are crowded around a card table in observation of the trick-taking game being played between the younger and older gentlemen.

Caillebotte is particularly famed for his ability to portray a perspective of depth in his paintings, a quality especially prominent in his paintings of balcony and window views. Though not as notable in Game of Bezique, the man seated on the sofa in the distance certainly contributes a depth perspective to the painting, as he seems far removed from the action and somewhat generally out of place. Perhaps he does not know how to play, or maybe there is a more metaphorical purpose to his inclusion. Perhaps his presence symbolises a depressive state which renders him incapable of enjoying social and trivial activities such as a card game amongst friends.

Though Brown had himself endured the hardships of an impoverished childhood, the street urchins depicted in his paintings were always cheery and healthy-looking. Paintings of anything too grim or sordid would have been unpopular with the upperclass, to which the majority of Brown’s commissioners belonged. In this particular painting we see two poor children, with ripped clothes and dirty feet, deeply immersed in a card game. The title Bluffing might suggest the game is some variation of poker; however the boys could also be playing ‘cheat.’ The mischievous and smug look on the boy to the left indicates he is the one ‘bluffing,’ whilst the other boy frowns with frustration as he looks down upon his cards. The pale and plain background focuses our eyes on the boys and their cards – indeed, the boys themselves seem totally absorbed by the game. Brown was known to have said he painted underprivileged boys because he, too, “was once a poor lad like them.”2 A pack of cards would have offered plenty of pastime for poor children without many toys. Perhaps Brown had fond childhood memories of playing cards on the streets.

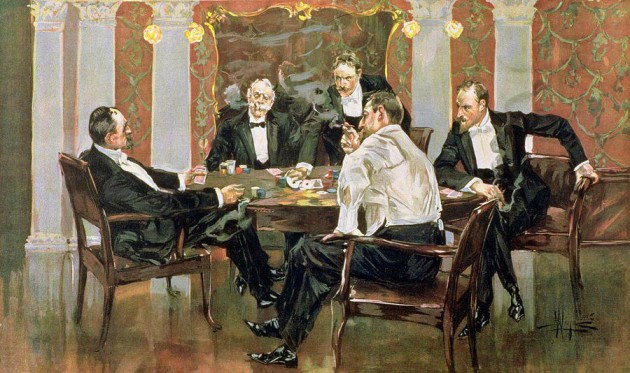

Wenzell’s paintings typically depicted scenes of wealth and optimism, reflecting the Belle Epoque age in which he lived. His subjects and setting were fantastically exaggerated with opulent detail and radiant colours, accurately capturing the wave of content that moved across the West at that time. Wenzell had himself grown up in a wealthy environment and been educated in Paris and Munich. Painting what he knew, Wenzell portrayed the luxurious and somewhat hedonistic lifestyle of the era’s upperclass. The artist was usually commissioned by rich American families who wanted artwork that depicted casual yet glamorous scenes. Wenzell therefore focused on beautiful, fashionably clad women interacting with older gentlemen in a familiar home setting.3 In A Showdown, however, Wenzell portrays only men, chewing cigars and dressed in business suits, engaged in what appears to he be the later stages of a poker game. Special attention should be given to the body language of all players. It seems almost as if the men are attempting to adopt a relaxed pose to ease the tension, but end up looking especially rigid as a result. The gentlemen to the far right looks particularly distressed, whilst the gentlemen to the left is slouching so far back in his chair that he looks uncomfortable. The painting’s title A Showdown confirms the confrontational and competitive nature of the scene. In poker, ‘showdown’ is the term used to describe the requirement for final players to show their hands at the end of the game. Clearly, a dramatic moment is about to unfold.

Dogs aren’t the only animals to have been painted at the card table. American painter Beard had a fascination with nature and famously portrayed wild animals in a disturbingly humanistic manner.4 The Poker Game is particularly unsettling in its depiction of chimps in Renaissance or Baroque clothing, gathered around a table. Most of the chimps are deeply concentrated on the card game at stake, though the servant and monk merely observe. Another chimp seems to be advising one of the players, whose four cards in hand, along with a fifth being passed to him, would indicate they are playing a five-card draw. The dark, stone setting and candlelight seems to imply the scene takes place in a castle room. Perhaps the non-participating chimp to the far left is the king, watching his subjects play cards and drink wine.

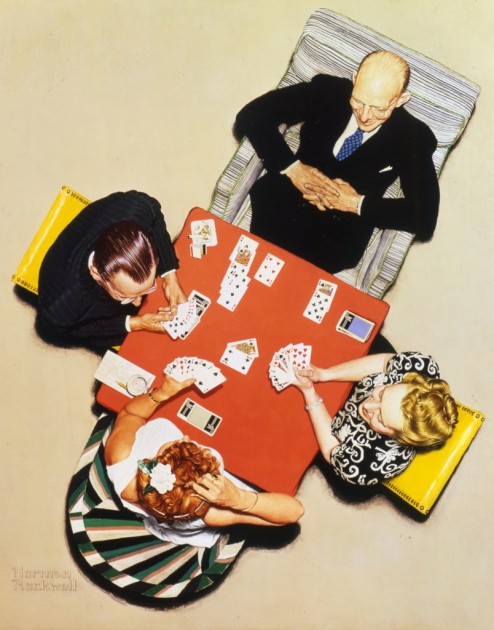

Rockwell’s influential art has undoubtedly become symbolic of American culture. Characterised by sunny colours and cheerful scenes, his illustrations depict sportsmen, industrial workers and the atomic family – all of whom in some way represented the American Dream. During the war, his paintings instilled a sense of righteousness and triumph, a sentiment with which the American government was keen to inspire people when they published Rockwell’s art as motivational posters. In The Bid, Rockwell depicts a casual and pleasant card game between friends in post-war America. The sandy floor, bright shades and sleeveless shirts of the women suggests the subjects are playing during the summer. Contrasting businessmen with a beach-like setting, Rockwell blends business with pleasure – reflective of the upper class lifestyle in late ’40s America. The mismatch of chairs is a charming detail, as it implies the seating was arranged hurriedly and without care, as if the card game was a spur-of-the-moment idea. Along with good company and good weather, the subjects in this postcard-esque painting are said to be enjoying a game of ‘Bridge.’

The very distinctive style of LeRoy Neiman can be characterized by his brisk brush strokes and hazy colouring, a method which seemed to capture the motion of his subjects and atmosphere of his setting. There are few places as bright and bustling as a casino, which perhaps explains with Neiman chose Vegas as the setting for so many of his artworks. Titled simply Stud Poker, this lively depiction of players around a card table is curiously reminiscent of Monet’s gardens. Indeed, the colourful chips on the green card table might as well be lillies in a pond. When looking at the poker players in closer detail, one can start to differentiate the features of each character, most of whom appear to be formally-dressed men – with the exception of a red-headed woman. Vibrant, busy and modern; the impressionistic and expressionist Stud Poker is a perfect example of Neiman’s eccentric style.

Most fascinating, when comparing the depiction of card games in art, is a consideration of how these games can be said to transcend social class. Not only have card games been infallibly popular over the past centuries, but they have always appealed equally to peasants as they have to kings. Another aspect worth studying is how the type of card game depicted in art changes depending upon era and, at times, the nationality of the painter. One should also note how, in the last two 20th century paintings sampled above, there are women participating in the games. This marks a shift in social attitudes, reflecting the move from ‘gentlemen’s poker nights’ toward a tendency of more gender-inclusive games. The final facet worth considering is how the depiction of gambling in art has often hinted toward its legal status during the artist’s era. Whilst many popular works of art have portrayed betting activities taking place in dark back rooms, between shifty and drunken characters, paintings such as Neiman’s Stud Poker shows the incorporation of gambling into mainstream culture. In short, the depiction of card games, as seen in works of art, can offer us insight into the unique and fascinating role these social yet competitive games play in our society.

[1] Gustave Caillebotte, The Complete Works, Early Life, 2009

[2] Birmingham Museum of Art, ‘Three for Five’ by John George Brown, 2012

[3] Society of Illustrators, Hall of Fame, Albert Beck Wenzell, 2005