Saturday, July 28th, 2012

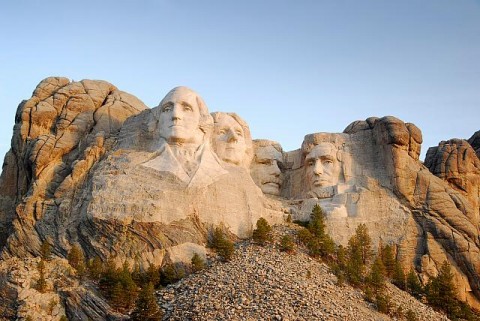

Mount Rushmore and the Statue of Liberty

Fréderic-Auguste Bartholdi, "Liberty Enlightening the World" (known as the "Statue of LIberty"), 1870-86. Hammered copper over wrought-iron pylon designed by Gustave Eiffel. Height from base to top of torch 112' (33.5 m). Image courtesy Wikipedia.

I have a quite a hoard of art history books in my possession. Out of all of my books, I only have one survey textbook which mentions the Statue of Liberty.1 None of my textbooks mention Mount Rushmore. Since these monuments have iconic status in American culture, I was surprised to realize yesterday that these monuments don’t really factor into the realm of art history (especially in the United States). Likewise, the sculptors Bartholdi and Borglum are hardly household names among Americans.

My husband and I discussed this topic yesterday, after seeing an image of Mount Rushmore on a television screen. We came up with a couple of theories as to why these monuments are not discussed in art history very much. I thought I’d jot them down here, and see what others think:

- These sculptures are not studied in art history because they aren’t influential. (My husband put forward this idea. I have some issues with this theory, because the word “influence” can be defined in different ways. Perhaps nineteenth-century artists did not copy Bartholdi’s sculpture, but the Statue of Liberty factors into Pop art, as can be seen in the work of Andy Warhol and others.)

- These sculptures are not the best representatives of the art which was popular in the late 19th and early 20th century. As a result, textbooks and instructors opt to discuss other works of art.

- These sculptures didn’t have international influence, which could account for their omission in broader, internationally-focused textbooks.

- These works are relatively ignored by art historians because they are recognized (either consciously or subconsciously) as monuments instead of sculptures. Along these lines, perhaps the iconic status of these sculptures precludes these pieces as being examined as works of art.

- Perhaps the location of these sculptures (i.e. in a harbor and on a mountainside) do not encourage the pieces to be appreciated for aesthetic reasons. Although I think that these sculptures are just as iconic as Michelangelo’s “David” (at least among Americans), these two sculptures are not displayed in an art museum.

- Since the creation for each of these monuments is connected to socio-political history, these sculptures have been overlooked in the art historical discipline. (Could this perhaps be indicative of how the disciplines of history and art history do not always intersect?)

What do others think? Did you ever learn about the Statue of Liberty or Mount Rushmore in an art history class? If so, what did you discuss? If you’re curious to learn more about these two American monuments, I have a few sites and images to recommend:

- The History of the Statue of Liberty (National Park Service)

- Statue of Liberty Pictures: Rare Views, Inside and Out (National Geographic)

- Sabotoge in New York Harbor (Smithsonian). This article is about the Black Tom explosion on July 30, 1916. The explosion caused over $100,000 of damage to the Statue of Liberty. Ever since this event, the interior of the torch has been closed to visitors.

- Sculptor Gutzon Borglum (.PDF file, National Park Service)

- The Making of Mount Rushmore (Smithsonian)

- Gutzon Borglum’s Model of Mount Rushmore (The original design was never realized, due to lack of funding.)

- Construction of Mount Rushmore (short video clip, Human Films Studies Archives, Smithsonian). Notice how the head of Thomas Jefferson was originally placed on the left of George Washington. Jefferson’s unfinished head had to be blasted off, however, due to poor rock quality. Borglum then placed Jefferson’s portrait on the other side of Washington’s portrait.

1 David G. Wilkins, Art Past Art Present 6th ed., (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2009). 432.