Saturday, June 20th, 2015

Wayne Thiebaud and Jim Gaffigan

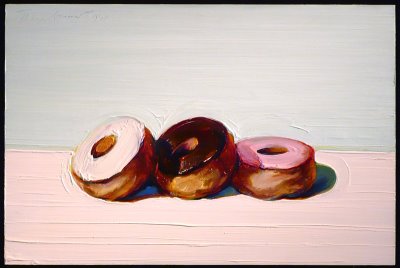

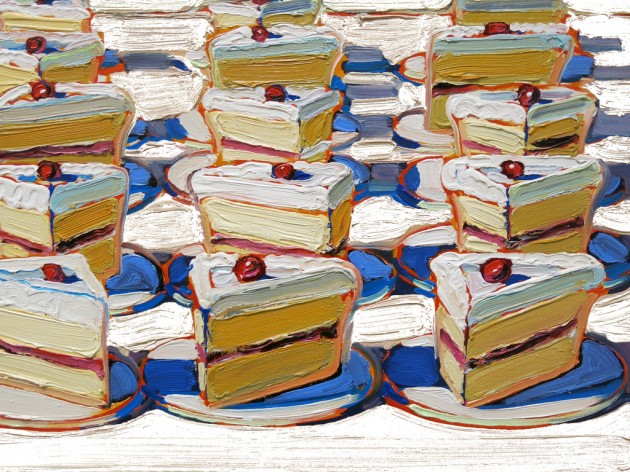

I’ve been thinking about Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings today, mostly because I have eaten way too many chocolate doughnuts over the past few days. Thiebaud doesn’t have as many paintings of doughnuts as he does of cakes and other sweets, but he does have a few (such as the one shown above, or this one of doughnuts and cupcakes).

The thing that I love most about Thiebaud’s paintings of desserts is his handling of the paint itself. Thiebaud applies the paint thickly; it almost feels like he’s painting with frosting itself (see detail below). The desserts have a true sense of tactility, which I think makes them seem even more desirable as tasty treats! (I guess it’s a good thing that Cookie Monster didn’t see a Thiebaud painting in when he visited art museums in New York earlier this year, or he would have tried to eat it!)

Wayne Theibaud, detail “Folsom Street Fair Cake,” Crocker Art Museum, 2013. Image courtesy torbakhopper via Flickr and Creative Commons License

Thinking about Wayne Thiebaud has also reminded me of Jim Gaffigan’s standup comedy, which often is about his love of delicious-yet-unhealthy food. Gaffigan must not have been aware of Thiebaud’s art before he made his joke about artists and still life paintings. This is what Gaffigan says in his show Obsessed about fruit (a healthy type of food that he dislikes!):

“…we haven’t wanted [to eat] fruit for hundreds of years. That’s why there’s so many paintings in museums of just bowls of fruit. Because you could start painting a bowl of fruit, you could leave for a couple of days, come back, and no one would have touched the bowl of fruit. But if you’re painting a doughnut? You better finish it up in the first sitting! You can’t even take a bathroom break – ‘Hey, what happened to my doughnut?’ Your friends are [like], ‘Oh, some fat guy came in here! Anyway, I’m going to get some milk and take a nap.’ That’s why there’s no doughnut art. It’s sad, really. When’s the last time you saw a painting of a doughnut?” (Audio clip of Obsessed found HERE, starting at 2:34).

To be fair though, it’s good to acknowledge that Wayne Thiebaud paints his doughnuts and cakes “from his imagination and from long-ago memories of bakeries and diners.”1 So, maybe Thiebaud just likes to eat doughnuts and cakes too, and he doesn’t have the patience to study them! Thiebaud does, however, also paint from life: he paints human figures (such as his wife Betty Jean, who is shown on the left in Two Kneeling Figures), and also sketches California landscapes outdoors and then returns to his studio to paint.

Anyhow, do you know of other images of doughnuts, cakes or other treats in art, besides those by Thiebaud? I thought of a few:

- Claes Oldenburg, Floor Cake, 1962. MoMA.

- Claes Oldenburg and Coosje Van Bruggen, Shuttlecock/Blackberry Pie II, 1999. Metropolitan Museum of Art (Roof Garden). There are several other iterations of these pies, including this one and Blueberry Pie à la mode, Flying.

- Claes Oldenburg, Giant Wedge of Pecan Pie,” 1963. Seattle Art Museum.

- The doughnut in Springfield, Australia (created in honor of The Simpson’s Movie from 2007), which is now in storage.

1 Cathleen McGuigan, “Wayne Thiebaud Is Not a Pop Artist!” Smithsonian (Feburary 2011). Available online: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/wayne-thiebaud-is-not-a-pop-artist-57060/?no-ist