Monday, November 9th, 2009

Vasari writes that Fra Filippo Lippi made a conscious decision to stop including a lot of hands in his paintings. Apparently, Lippi had been criticized for including too many hands in his compositions, and someone advised him to be aware of that fact.1 Lippi received this sound advice around 1445, and Vasari writes that in later paintings Lippi “covered [the hands] up with draperies or some other invention in order to avoid such criticism.”2

In some ways, you really can see a switch from the “hand” to “hand-free” Lippi. (Okay, in truth, his later paintings aren’t “hand-free,” but often there aren’t as many hands.) Here are some earlier, “handy” paintings:

St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio

St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio, c. 1438

There are

way too many hands in the group on the right. And look at the man who is standing on the left side of that group – his hands are awkwardly included in the composition to the point of distraction. It almost looks like that man is going to box the ears of the pious man who is kneeling down.

Madonna of Humility (Trivulzio Madonna), c. 1430

Madonna of Humility (Trivulzio Madonna), c. 1430

(with red circles added – click here to see a reproduction without circles)

I think this painting is pretty ugly, and the plethora of hands doesn’t help the composition one bit. I circled sixteen different hands. Granted, there are a lot of figures in this painting, but sixteen hands seems a little extreme and unnecessary. Hands pop out in some of the strangest places, too. Check out some of the hands on the left-side of the Virgin.

Lippi’s post-1445 (ahem, post-“handy”) works still include hands, although he often (but not always!) toned down the number of hands and was a little more tactful.

Detail of

Disputation in the Synagogue, 1452-65

Notice how Lippi covered up the figure on the left’s hands with drapery? Smart move. There aren’t any miscellaneous fingers or palms sticking out anywhere, either, which is an improvement.

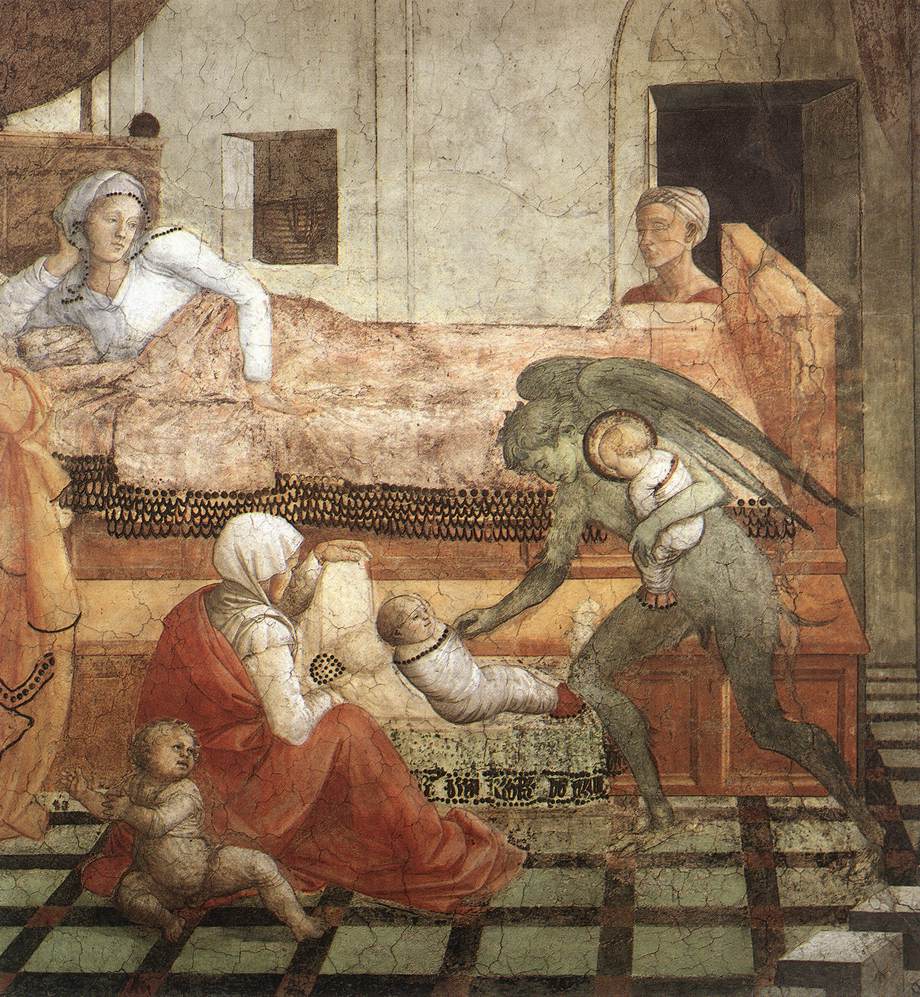

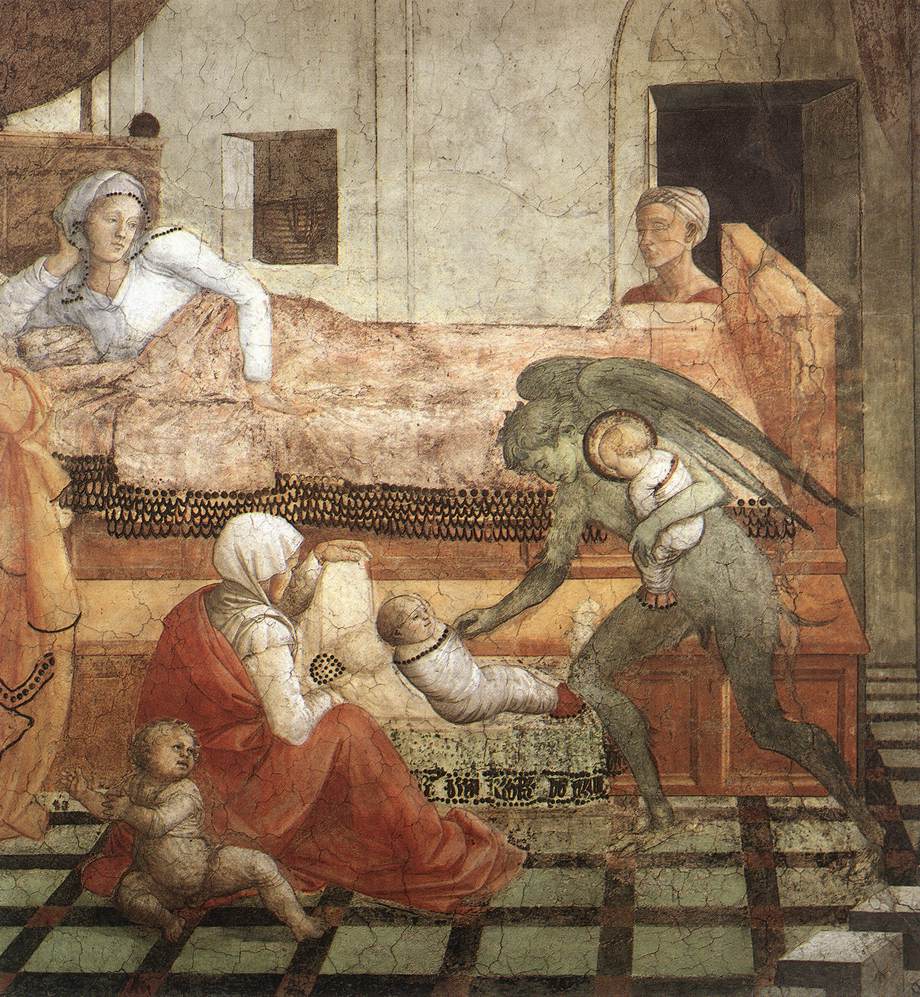

Detail of

St. Stephen is Born and Replaced with Another Child, 1452-65

Lippi toned down the hands a bit in here – Stephen’s mother covers up one hand with her head, and the seated woman covers up a hand with her knee (although I think her other hand is awkward in its position and placement). And you don’t even see the hands of the figure behind the bed. I think, though, that the woman on the left’s hand is poking out from behind her cloak – it’s a little awkward since its the only part of the woman that we can see, but hey, this is an improvement for Lippi.

Do you know of a “handy” or “hand-free” work by Lippi? What do you think – did Lippi improve by toning down his inclusion of hands? I certainly think so.

1 Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, translation by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), 194.

2 Ibid.

Thursday, November 5th, 2009

It’s always interesting to see how an artist depicts an animal that he/she has never seen. Vasari writes that Paolo Uccello wanted to depict a chameleon his Four Seasons, but since the artist had never seen a chameleon, he opted to draw a camel instead.1 I guess you can kind of see Uccello’s logic in picking a camel, since camaleonte and camello are similar words in Italian (the two words are a little similar in English, too). I wish that Uccello’s Four Seasons still existed; I’d love to see what that chameleon/camel looked like.

Durer attempted to depict a rhinoceros, even though he had never seen one. He really didn’t do

too bad of a job (see woodcut print

The Rhinoceros (1515) on the right), although the armor-like plates are a little funny. Durer became interested in the rhino after seeing a sketch and reading descriptions in a letter from Lisbon.

2 The year that Durer made this print, 1515, was a big year for rhinoceroses in Europe. Both the king of Spain and king of Portugal were trying to win the favor of the pope by giving him rhinoceroses. The pope apparently liked the West African rhino (the gift from Spain) best, which allegedly answers why the pope gave more New World territory to Spain.

3 I bet that Durer was trying to maximize on the interest in rhinoceroses during this year, since woodcut prints can be widely distributed, popularized, etc.

There are other animal depictions which I think are amusing. When writing my thesis, I would often chuckle at Aleijadinho’s depiction of a lion. Since the Brazilian artist had never seen a lion before, he sculpted this one with the face of a monkey:

Aleijadinho, detail of lion next to the prophet Daniel, 1800-1805

And you have to love Aleijadinho’s great attempt at a whale. I especially love the whale’s two spouts (kind of like nostrils, I guess) and fins:

Aleijadinho, detail of whale next to the prophet Jonah, 1800-1805

Aleijadinho, side-view of Jonah’s whale, 1800-1805

Aleijadinho, side-view of Jonah’s whale, 1800-1805

Medieval bestiaries are full of creative depictions of animals. I particularly like

this depiction of a crocodile and

this depiction of an elephant (check out those tusks and horse-like flanks!).

I know there are lots of other interesting/creative/bizarre depictions of creatures that have resulted from the artist never seeing the actual animal. What ones do you know? Do you have a favorite? Let’s see who can give the most bizarre example…

1 Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, translation by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), 82.

2 “The Rhinoceros,” in Web Gallery of Art, available from , accessed 5 November 2009.

3 Hemanta Mishra, Bruce Babbitt, Jim Ottaway, Jr.,

The Soul of the Rhino (Guilman, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2008), 137. Available online here.

Monday, November 2nd, 2009

If I asked you what was in this detail of Caravaggio’s Bacchus (1597), and you answered “A carafe of wine,” you would only be given partial-credit for your answer. Sorry. This detail, my friends, has been found to contain an early self-portrait of Caravaggio at his easel, shown as a reflection in the glass carafe.

You’re aren’t seeing it, you say? To tell you the truth, me neither. In actuality, you can’t see this detail with the naked eye. It used to be visible, however, since it was mentioned by an Italian restorer in 1922. However, poor restoration efforts and the gradual darkening of this image have obscured this small portrait over time. Only recently did the portrait “resurface” through reflectography, and the image results were revealed last Friday at a conference in Florence.

You can kinda-sorta see the portrait of Caravaggio in

this Telegraph article, which posted the reflectography results and circled where the portrait is located. I’m still not seeing too much, but I’m trusting that one can actually see a young Caravaggio, paintbrush in hand, with his arm extended toward a canvas on an easel.

Pretty cool, huh? I wonder if restorative efforts can make this self-portrait visible again to the naked eye.

St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio, c. 1438

St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio, c. 1438 Madonna of Humility (Trivulzio Madonna), c. 1430

Madonna of Humility (Trivulzio Madonna), c. 1430 Detail of Disputation in the Synagogue, 1452-65

Detail of Disputation in the Synagogue, 1452-65 Detail of St. Stephen is Born and Replaced with Another Child, 1452-65

Detail of St. Stephen is Born and Replaced with Another Child, 1452-65