Monday, September 28th, 2009

"Dark Water": Florence Flood of 1966

Tonight I finished reading Dark Water (by Robert Clark) as part of Heidenkind’s Art History Challenge. This book focuses on the 1966 flood in Florence which ruined and threatened many works of art. I liked a lot of things in this book, particularly in the middle section where Clark discusses damaged art/books and restoration techniques. I have to admit, though, that Clark’s writing style and half-baked themes about Icarus/water/Ruskin were annoying.

Anyhow, I was most fascinated about how much damage was caused by this flood (which was around 20′ deep in some areas). Clark writes that some 14,000 moveable artworks were damaged or destroyed.1 The Biblioteca Nazionale also suffered extensive damage; 1.3 items needed restorative work and 8 million catalog cards were inundated.2 It was also interesting to read about the innovative things that art/museum directors did to save pieces of history and culture – I particularly enjoyed reading about how the science museum’s director escaped the flood by walking along the roof towards the neighboring Uffizi gallery, while cradling Galileo’s telescope in her arm.

Here are some pictures taken right after the flood (by LIFE photographer David Lees):

Interior of the Basilica of Santa Croce, 6 November 1966

Interior of the Basilica of Santa Croce, 6 November 1966(Look at all that mud!)

Moving Paintings in the Piazza Signoria, 6 November 1966

Moving Paintings in the Piazza Signoria, 6 November 1966 Flood Damaged Books, 1966

Flood Damaged Books, 1966

Pretty crazy, huh? Does anyone have any recollections from when this flood occurred?

A large portion of the book discusses the destruction and restoration of Cimabue’s Crucufix from Santa Croce (c. 1288). Water damaged a good portion of the painting, and it took about ten years for the huge piece to be restored (partially because the wooden cross had absorbed so much water). There was a lot of controversy as to whether the cross should be restored at all, since there was so much damage. Ultimately, it was decided that overlapping trateggio (hatching applied with a fine brush) would be placed in the damaged areas, so that the viewer could see the damage but also get a sense of the original composition. I know that some restorers still disagree with how the Crucifix was restored, but it seems to me like the restoration team did a their best, given their limitations.

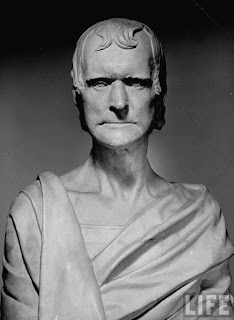

Here’s a picture of the original crucifix (photographed before 1966):

And here are two post-restoration photographs (the first one is from 1977):

What do you think of the restoration? Do you wish that the area was painted over to give a semblance of Cimabue’s original work, or do you like that the restoration recognizes the damaged areas?

All in all, Dark Water was a pretty interesting book to read. I found the beginning and end of the book to be a little boring, but the bulk of the book was quite fascinating.

1 Robert Clark, Dark Water: Flood and Redemption in the City of Masterpieces (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 162.

2 Ibid., 225.