Monday, January 22nd, 2018

Stags and Elk in “Adam and Eve” scenes

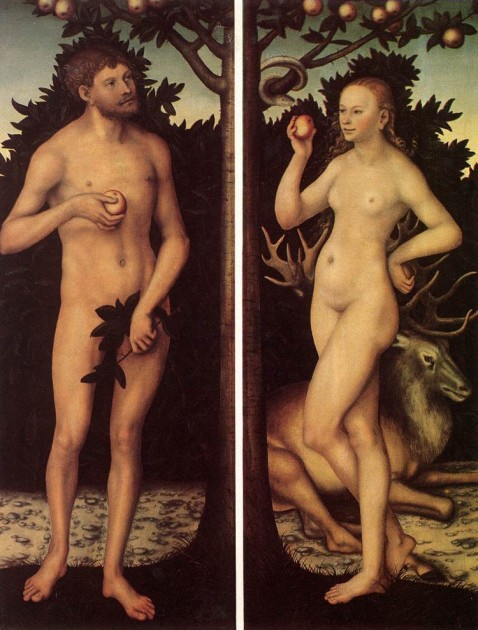

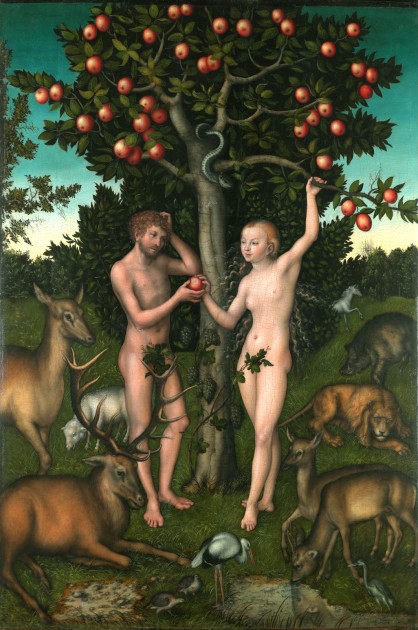

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), Adam and Eve, 1526. The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

I have been combing through dozens of paintings of Adam and Eve this morning by Lucas Cranach the Elder. I knew he painted several versions, but I had no idea that he painted so many! I’ve been struck at seeing the different animals that Cranach chose to depict within the Garden of Eden, especially since these images by Cranach are influenced by Dürer’s Adam and Eve engraving of 1504. However, Cranach’s animals don’t have the same symbolic meaning relating to the four humors that Dürer intended. Instead, the Courtauld Gallery points out that their version (shown above) includes a multiplicity of animals that are “less solemn and portentous” than Dürer’s few animals. Cranach’s animals seem to suggest the exotic and lively environment within the Garden of Eden, which the Courtauld Gallery describes as a “seductive vision of Paradise.”

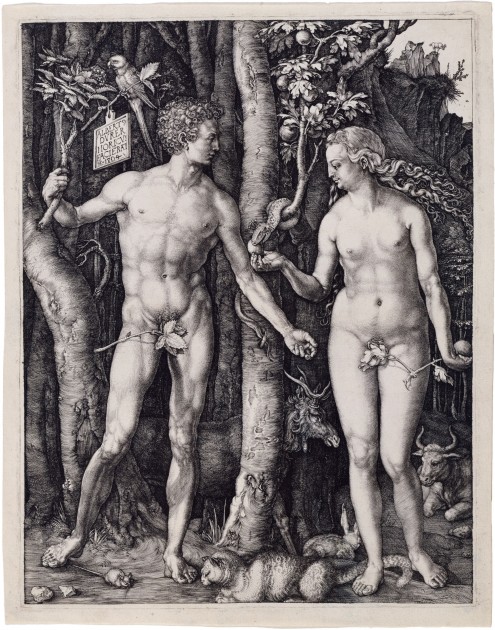

Dürer’s Garden of Eden seems less seductive: there are clearly identifiable animals, but they aren’t visually-celebrated and displayed in the same way as the Cranach painting (notice Dürer’s rabbit is turned away from the viewer). Instead, these animals serve a symbolic purpose. According to Erwin Panofsky, four of the animals each represent one of the four humors and their associated temperaments, which is something that I have written about previously.

One particular animal in Dürer’s print is striking to me: the elk was seen as a symbol of melancholy, one of the four humors. I wonder if Dürer ended up thinking about this animal in a different way later on in his career: a few years after this print was created, a philosopher in Germany named Agrippa of Nettesheim connected the melancholic temperament specifically to creative, imaginative people involved in the arts.1 Dürer himself references to the melancholic temperament and the creative genius in later works of art: the Melencolia I engraving from 1514 is thought by some to be an allegorical portrait of the artist himself. Could Dürer have felt any sort of connection with the elk as an animal, after knowing of this connection between the melancholic temperament and artists? He did also complete a drawing of an elk, but the date of the drawing is disputed and unclear.

Since Cranach and Dürer were contemporaries, I began to wonder if Cranach depicted any elk that could possibly reference the melancholic temperament. However, I learned that Cranach rejected the idea of the Renaissance genius and the hubris of humanism, so it makes sense that he wouldn’t be interested in including symbols of the four humors. Furthermore, I noticed that Cranach’s paintings clearly depict stags instead of elk. There is a clear difference between these animals! Stags are much bigger than elk (see this photo). Cranach also makes an effort to depict the shaggy neck/chest mane that is characteristic of stags (see painting above), to make sure that the stag is clearly identified.

But why stags? This also has symbolic meaning, but in a different way than the elk. Since the medieval period, stags were viewed as a symbol for Christ and Christians. Just as a stag can escape the hunter or a predator, Christ was able to escape the devil and the permanence of death. Similarly, a Christian could also escape the snares of the devil through emulating Christ and living a virtuous life.1 Cranach emphasizes this idea by showing a stag pulling back from a predatory lion in his 1533 painting of Adam and Eve in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin.

It’s revealing to me that Cranach often depicts the stag appears behind Eve (shown above) or peeking behind Adam (as seen in this 1528 example in the Detroit Institute of Arts collection), too. This seems intentional because Adam and Eve are not following the “escapist” behavior of the stag, but instead are falling into the trap of sin by partaking of the Forbidden Fruit. Therefore, the stags in these paintings serves as a reminder for the need of Christ, since sin enters into the world due to Adam and Eve’s actions.

So, both the elk and the stag can relate to the idea of imbalance due to the introduction of sin: either the imbalance of the four humors or the need for mankind to find redemption through Christ. I think that Dürer was able to include a more obscure reference to the four humors, since his engraving was intended to produce a smaller amount of prints that would have been circulated in humanist circles that understood the reference. In contrast, Cranach included a traditional medieval symbol with his stag, which explains why he felt comfortable reproducing the stag in numerous paintings, since he knew his broader audience would be more familiar with such symbolism.

1 Paul Wood, “Genius and Melancholy: The Art of Dürer,” in The Changing Status of the Artist by Emma Barker, Nick Webb, and Kim Woods, eds. (Open University Press, 1999), p. 156-157. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=A_1Ady0GAuUC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA156#v=onepage&q&f=false

2Lindsey Nicole Blair, “Cats and Dogs: The Development of the Household Pet through Symbolic Interpretations and Social Practices in the Middle Ages and Renaissance,” in Iowa Research Online (Summer 2016): 15-16. Available online: http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=honors_theses