Saturday, August 14th, 2021

William Morris and Children’s Classics

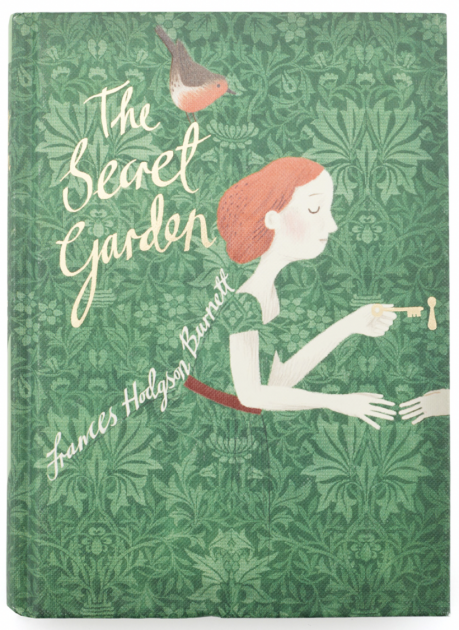

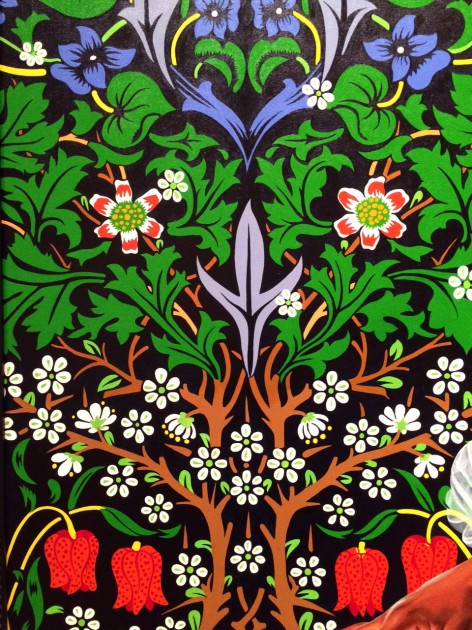

Yesterday I finished listening to an audiobook of The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I have loved that story since I was a girl and it was fun for me to revisit the book. While I was looking up some favorite quotes from the text, I came across a Puffin classic collector’s series which incorporates William Morris designs into the covers of the books. All of the covers are designed by Liz Catchpole, who collaborated with the V&A Museum in order to choose Morris designs from the museum’s collection. This is the cover for The Secret Garden in the series:

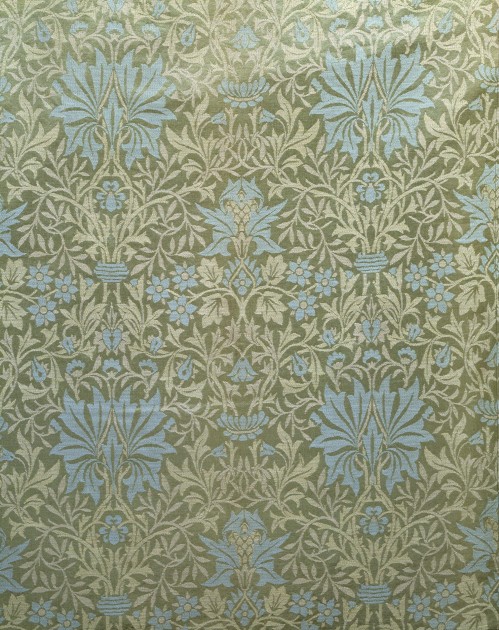

The William Morris design chosen for this cover is “Flower Garden” from 1879, which is a very appropriate title for a book about a garden! However, it should be noted the flowers in the Morris design differ from the ones mentioned in the book. The Secret Garden book mentions lots of flowers, including snowdrops, roses, daffydowndillys (daffodills), crocuses, irises, delphiniums, primroses, poppies, and cherry blossoms. By contrast, the “Flower Garden” design includes stylized flowers that look like snakeshead (fritillary) and borage. There doesn’t appear to be any ivy, so the quote on the back of the book cover about the “swinging curtain of ivy” is less relevant to the Morrisian design.

William Morris, “Flower Garden,” 1879. Furnishing fabric of Jacquard-woven silk and wool, made at Queen Square Workshop and at Merton Abbey Workshop, England. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Used with permission.

All this being said, though, I still love the use of the Morris design for this book cover. I think that having the “Flower Garden” pattern used as part of Mary’s dress is clever in two ways: 1) it complements how this design by Morris was used to make 19th-century textiles at Merton Abbey and 2) the thriving foliage foreshadows the positive growth and internal change that Mary Lennox experiences as she lives as Misselthwaite and cares for the Secret Garden.

The V&A Store explains on their website how each of the books in the collector series are held within the National Library. These are the other books in the series, along with the Morris designs chosen:

- The Wind in the Willows cover is Morris’s “Willow Bough” design (1887). I think this choice is so appropriate, especially because the leaves overlap and curl as if they are being moved by the wind.

- The Anne of Green Gables cover is Morris’s “Bird” design (1878). This design reminds me a little of a quote that Anne says while she travels with Matthew to Green Gables from the train station: “If you were out in a great big woods with other trees all around you and little mosses and June bells growing over your roots and a brook not far away and birds singing in you branches, you could grow, couldn’t you?”1

- The Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland cover is appropriately decorated with Morris’s “Brother Rabbit” design (1880-1881) to reference the White Rabbit.

- The Little Women cover is Morris’s “Larkspur” design (1875). I don’t see a clear connection between the design and Jo on the cover. But larkspur is mentioned in the book at the beginning of Chapter 10, in a description of the different flowers that the four sisters grow in their respective quarters of the garden plot.

- The Peter Pan cover is Morris’s “Marigold” design (1875). I don’t see a direct connection to the book, although the dense foliage could perhaps evoke the forest of Neverland.

- The Jungle Book cover is the “Indian” design (produced 1868-70) used by Morris & Co. The V&A website explains that this design was not made by Morris, but was copied from an 18th-century wallpaper or may have been designed by architect George Gilbert Scott, whose company Watts & Co. produced some wallpapers. I can see why this cover was chosen, as the dense and spiky plants evoke a sense of a warm climate and jungle.

- The Treasure Island cover design is “Strawberry Thief” (1883). While the birds in the design only loosely relate to the parrot on Long John’s Silver’s shoulder, I think that the theme of thievery can serve as a loosely appropriate parallel between the design and the pirate rogues in the book.

And in case you are curious, the William Morris designs are only on the covers of the books, and not part of any illustration within the texts themselves. (One reviewer has wondered if it would be possible for Liz Catchpole could illustrate the pictures within the text too.) I know Liz Catchpole has done a few other designs for books that include William Morris patterns, including The Twelve Days of Christmas, William Morris ABC and William Morris 123. If you know of other children’s books which incorporate William Morris designs, please share!

1 L. M. Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables, first published 1908. Quote is from Chapter 2 and found online here.