Thursday, May 24th, 2012

Mosaic Restorations at Hagia Sophia

This summer I am going to Istanbul (and other parts of Turkey) with some old roommates from college. One of the things that I am most excited to see is Hagia Sophia. This church-mosque-museum has such a rich, nuanced, and even rough history.

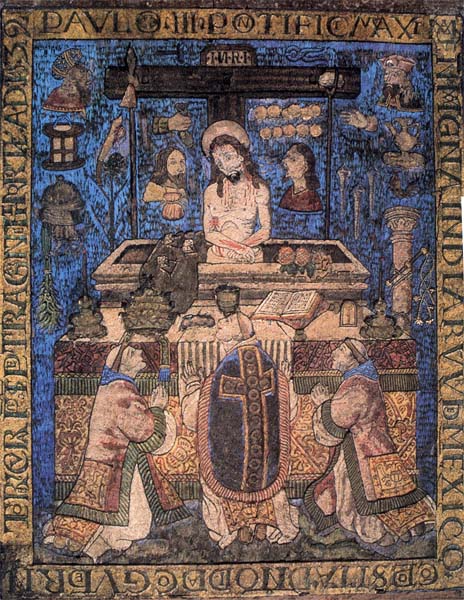

Lately I’ve been thinking about the mosaics located inside Hagia Sophia. These mosaics, which were created over several centuries, have had a hard time due to earthquakes and other forms of damage. The early mosaics were removed during the latter part of the 720s as a result of iconoclasm, only to be returned under the rule of Empress Irene (752-803). Later, with the sack of Hagia Sophia under the Fourth Crusade of 1204, some mosaics were removed and sent to Venice. Other relics from Hagia Sophia also ended up in Europe during this same time.

After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque. Subsequently, perhaps over time, the mosaics were covered up with plaster and painted decorations.1 To finalize the process, the mosaics were uniformly covered with plaster sometime between 1847-1849, at the request of Ottoman ruler H. M. Sultan Abdul Medjid.2 The widespread covering of mosaics was part of a project to help give more strength, uniformity, and consistency to the structure, which had weakened and been subject to many modifications over the past several centuries. Old plaster had also fallen off some of the mosaics, and Medjid wanted the mosaics to be restored (i.e. removing the remaining old plaster) and then covered with new plaster.

This 19th century project on Hagia Sophia was overseen by Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati, two Italian brothers. These men oversaw a crew of more than eight hundred people. During this process, the Fossati brothers “recorded the location and description of many of the mosaics before replastering over them.”3

Seraphim in dome pendentive of Hagia Sophia, probably from the mid-14th century (post-dating an earthquake of 1344). The face of this seraphim was covered by the Fossati brothers in the 19th century. About one hundred and sixty years later, the face was uncovered and restored in 2009.*

In class yesterday, some of my students speculated that the covering of mosaics could have been done as an act of retaliation or anger against the Christians (perhaps as a result of the Crusades). From what I can tell, though, it doesn’t seem like the mosaics were covered to signify vengeance or even political domination. Instead, Muslims seemed to respect the original structure and its decoration.4 After all, the mosaics were covered with plaster instead of destroyed.

I have even read some discussion of how Muslims began to incorporate Hagia Sophia into their own cultural history, in order to justify the conversion of this structure into a mosque. These stories from Ottoman historical texts indicate to me that cultural appropriation of Hagia Sophia by Muslims was seen from more practical and religious viewpoints, instead of one that was riddled with spite. One version of this story relates that when the half-dome of the apse collapsed on the night of the Prophet Mohammad’s birth, it could only be repaired with a mortar composed of sand from Mecca, water from the well of Zemzem, and the Prophet’s saliva.5

The fate of the plastered mosaics would change again, after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in the 20th century. The mosaics began to be uncovered in 1931, and work continued until 1938. During this same time period, Hagia Sophia was turned into a museum by Kemal Atatürk. The space officially opened as a museum in 1935.

Restorations of the mosaics continued in the 20th century, and a major restoration took place between 1993 and 2010. This most recent restoration was fraught with its own difficulties, partially due to lack of consistent funding. And even though the Ministry of Culture and Tourism declared that the project was complete in 2010, there is still much more restoration work that needs to be done. In 2011, it was reported that many walls and passageways in Hagia Sophia were still covered with plaster. In the 19th century the Fossati brothers also recorded that a great Christ Pantocrator mosaic was located in the dome (among a number of other mosaics that are not visible today). I wonder if these mosaics still exist. Many are hopeful, including myself, that more mosaics are waiting to be uncovered.

*More information and pictures regarding the seraphim restoration can be found HERE.

1 We know that different individuals in the 17th and 18th centuries made some drawings of mosaics that they saw in Hagia Sophia. Evilya Effendi made some drawings of mosaics in the 17th century and Swedish traveler Cornelius Loos did some drawings in 1710. See Dr. Helen C. Evans, “Byzantium Restored: The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia in the 20th Century,” 4th Annual Pallas Lecture, University of Michigan, p. 2. Online copy of lecture available at: http://www.lsa.umich.edu/UofM/Content/modgreek/document/Evans_PallasLecture.pdf (accessed 24 May 2012).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 It has been noted, though, that there was some internal resistance from the conversion of a Christian structure into a mosque. Robert Ousterhout writes, “Yet tension remained, and the Christian memory was never entirely erased. A firman of 1573 indicates that there was still some opposition to the preservation of a building built by non-Muslims.” See Robert Ousterhout, “Ethnic Identity and Cultural Appropriation in Early Ottoman Architecture,” in Muqarnas 12 (1995): 49. Online copy of article available at: http://archnet.org/library/documents/one-document.jsp?document_id=8983 (accessed 24 May 2012).

5 Ibid., 49.