Friday, April 5th, 2013

Politics, the Capitoline Museum, and the She-Wolf

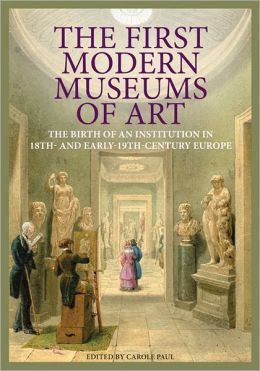

This quarter I am working with just a few of the senior art history majors on a special “Directed Study” course. We are exploring museum history and curatorial theory, using two new books: The First Modern Museums of Art: The Birth of an Institution in 18th- and 19th-Century Europe (2012) and New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction (2011). I really like that The First Modern Museums of Art is written in a very approachable, yet scholarly, way. Each chapter serves a case study for a different museum that was established; the book proceeds in a chronological fashion, based on founding dates for the institutions.

This quarter I am working with just a few of the senior art history majors on a special “Directed Study” course. We are exploring museum history and curatorial theory, using two new books: The First Modern Museums of Art: The Birth of an Institution in 18th- and 19th-Century Europe (2012) and New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction (2011). I really like that The First Modern Museums of Art is written in a very approachable, yet scholarly, way. Each chapter serves a case study for a different museum that was established; the book proceeds in a chronological fashion, based on founding dates for the institutions.

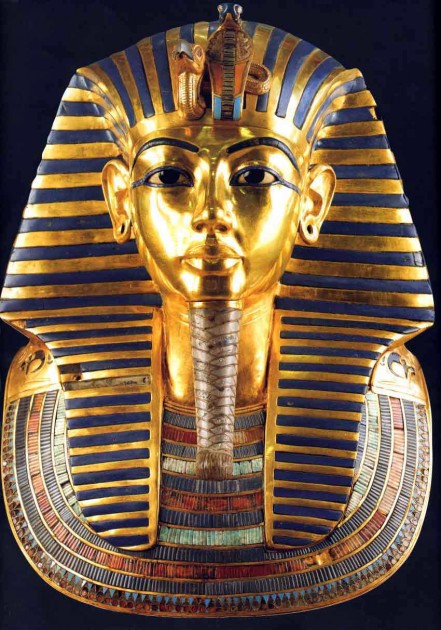

This week, my students and I read about the Capitoline Museum (established 1733). Carole Paul writes about how the objects within the museum serve as strong signifiers of political and cultural heritage. The museum, which contains a lot of Roman art, emphasizes Roman authority and jurisdiction. The artistic “progression” and superiority of Roman culture (and those Westerners who are heirs to the Roman tradition) are implied in many ways, including the display of art. For example, the visitor encounters Egyptian figures before the Greco-Roman antiquities, which suggests both artistic and political succession.

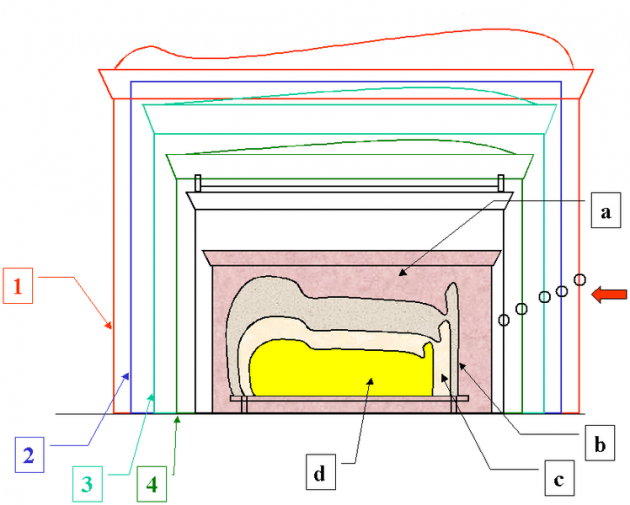

The political associations and signifiers of power also extend into the collection. I think it’s particularly interesting that the bronze sculpture of the she-wolf forms part of the collection, given the history of the piece. Before Sixtus IV donated this sculpture to the Compidoglio (Capitoline Hill), the she-wolf was displayed in the Lateran Palace, the pope’s official residence.1 This she-wolf was seen as a symbol of the city, since the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, were suckled by a she-wolf. As part of the papal collection, this statue then served as a symbol of papal jurisdiction and the papal succession of authority after pagan rule.

Given these associations with Roman history, I can see why the Capitoline Museum seemed a bit hesitant to acknowledge the recent analyses which determined that the “She-Wolf” statue was cast during the medieval period! This was big change in the traditional attribution, which placed this statue in the fifth century BC (as an example of Etruscan art). When I covered this story in 2010, over two years after the new study results were made available, I was surprised that the Capitoline Museum did not have the updated medieval date on its website! Now that I understand the political and authoritative statements behind the formation of this museum, though, I can see why the museum seems to have been hesitant to acknowledge this new information. The museum would want to endorse this as a work of art as an authentic piece from the Etruscan/pre-Roman period, in order to emphasize the institutional message of Roman authority. If the “She-Wolf” is a medieval work of art, there isn’t as direct of a connection to Roman history.

However, today I went back and checked the Capitoline Museum website again. Now the site has been updated to acknowledge the alternate date and also mentions the Carbon 14 analysis (albeit that the information is slightly hidden under a “Reveal text” button).

What have been your experiences at the Capitoline Museum? Did you feel like the message of Roman authority and power came through during your visit?

1 Carole Paul notes that this wolf (lupa) was in fact returned to its rightful home through Sixtus IV’s donation. Paul writes that the wolf “had originally stood on the Campidoglio and in 65 BC had been struck by a bolt of lightning that apparently broke her feet and destroyed the suckling twins, who were replaced only in the fifteenth century.” See Carole Paul, “Capitoline Museum, Rome: Civic Identity and Personal Cultivation” in The First Modern Museums of Art: The Birth of An Institution in 18th- and 19th-Century Rome, Carole Paul, ed., (Los Angeles: Getty, 2012), 22. Given that the she-wolf is now thought to have been produced in the medieval period, I personally think that Paul might be referring to a different depiction of a wolf (perhaps lost) or that this story might have been a myth. Paul cites a 1980 publication by Richard Krautheimer in relation to this story about the lightening bolt. Therefore, she does not seem take into account the more recent Carbon 14 analysis and medieval date.