Monday, February 10th, 2014

Manet’s Pavilion and the 1867 Exposition Universelle

Manet, "A View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle," 1867. Oil on canvas, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway

This afternoon, when my student gave a presentation on Manet, she mentioned that she found information about a pavilion that Manet set up during the 1867 Exposition Universelle (“World Fair”), near the grounds of the exhibition itself. At first, I worried that this student was referring to the “Pavilion of Realism” set up by the artist Courbet over a decade before. When Courbet’s monumental canvas, The Painter’s Studio 1854-1855) was rejected from the 1855 Exposition Universelle, Courbet set up his own pavilion – a circus-like tent – within sight of the grounds of the official site. There, Courbet displayed more than forty of his own works, including The Painter’s Studio. He also used his own exhibition as a means to propagate his own ideas: the exhibition catalog included Courbet’s famous “Realist Manifesto,” where Courbet proclaimed that he wanted to create “living art” by depicting modern life.

After my student’s presentation, I told my class about how the “Pavilion of Realism” is an example of how avant-garde artists sometimes seek alternate venues for displaying their art. Then I said that it wouldn’t be surprising if Manet had done a similar thing in Courbet’s wake, and I would look forward to checking into this point further.

Manet did host his own pavilion in 1867, between the 22nd and the 24th of May, since he was not invited to participate in the official show which was overseen by an exhibition committee. Manet’s pavilion was located near the grounds of the exhibition, near the Champs de Mars in L’Avenue d’Alma, just across the street from one of the entrances to the main grounds of the fair. At this same time, Manet also painted a picture (albeit one that was abandoned in its early stages) to commemorate the ongoing exhibition (see image above and read more information HERE).

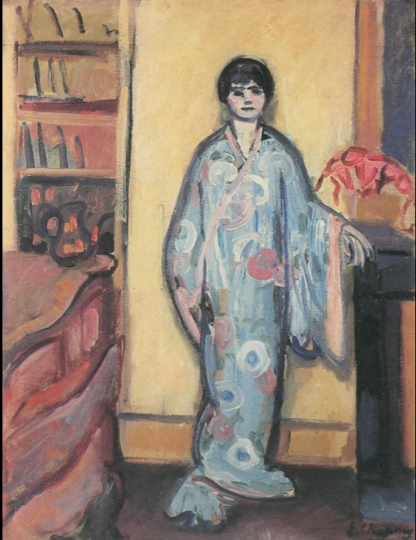

Manet’s pavilion included more than fifty works of art, including his by-then-notorious painting Le Dejuner sur l’Herbe (1863), which previously had been displayed in the Salon des Refusés in 1863. Other works of art included Young Lady in 1866 (Woman with a Parrot) and A Matador (1867, see below). Around twenty other paintings in this show revolved around Spanish themes, which evidences Manet’s penchant for the style and culture of artists like Velasquez (Manet had studied Velasquez when visiting the Museo del Prado in Madrid).

Manet, "A Matador," 1867. Oil on canvas; 67 3/8 x 44 1/2 in. (171.1 x 113 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art

Manet’s pavilion did not attract a lot of attention; it was ignored by both the press and the general public.1 To accompany the exhibition, Manet also “published a catalog with a short, unsigned preface, one of the few statements about his art that can be attributed to his own ideas (it has been presumed that he received help from his literary friends). In it the importance of exhibiting is stressed, and his work is characterized as ‘sincere’, one of the watchwords of the Realist movement.”2 (Note: I believe that ‘sincere’ is translated as ‘honest’ in the translation that is linked above).

The preface comes across as a little whiny too me – Manet seems to wallow in misery a little too much, oft complaining about his consistent rejection from the juries of the Salon. I do respect his assertion that it is important for artists to exhibit their work, but he seems to emphasize this point in too much of a defensive way. I also imagine that visitors to the pavillion would feel a little put-off by his statement that the “public has been supposedly turned into an enemy.” I wouldn’t want to enter a show, having just been accused as being an enemy of the artist!

I’m surprised that I didn’t hear about Manet’s exhibition before today. Why is Courbet’s “Pavilion of Realism” better known among art historians than Manet’s 1867 pavilion? On one hand, both exhibitions received poor attendance and not very much critical attention at the time they were mounted.3 My guess is that Courbet’s pavilion draws more attention from a historical perspective after-the-fact because 1) his own personally-funded retrospective exhibition was the first of its kind and 2) the “Realist Manifesto” is perceived as more groundbreaking and substantial than the ideas that Manet presented. Another reason is that it may be more appealing for art historians to focus on discussing the display of Manet’s work at the Salon des Refusés of 1863, simply because that story involves more dramatic content and ridicule.

I feel like general art history has abandoned a discussion of Manet’s pavilion somewhat, perhaps similarly to how Manet quickly abandoned his own painting of the 1867 Exposition Universelle (see image at top of post). Does anyone else have ideas as to why Manet’s pavilion isn’t frequently cited or mentioned in basic art history texts? Is there anything else that you know or appreciate about either Courbet’s exhibition or Manet’s exhibition?

1 Beatrice Farwell. “Manet, Edouard.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed February 11, 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053749.

2 Ibid.

3 For a discussion of Courbet’s Pavilion and its reception, see Stephen Eisenmann, “The Rhetoric of Realism: Courbet and the Origins of the Avant-Garde“, in Ninteenth-Century Art: A Critical History (London: Thames and Hudson, 2007), p. 221. Text available online HERE.