Tuesday, August 18th, 2015

Mirrors and Optical Effects in Ukiyo-e Prints

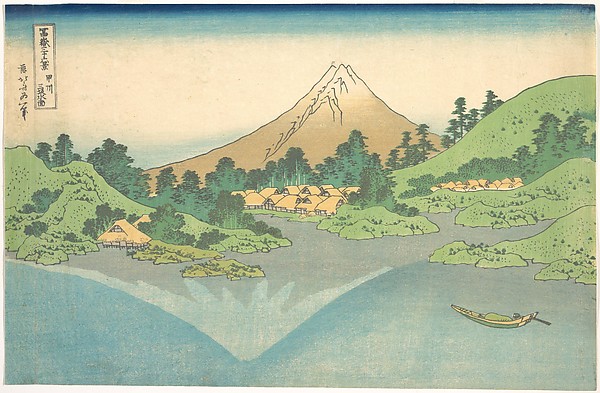

In a recent podcast on Hokusai from Stuff You Missed in History Class, I learned an interesting detail about Hokusai’s biography and background. Although it is difficult to create a comprehensive biography on Hokusai, we do know that his uncle was a mirror polisher. This was a skilled profession since mirrors were made out of bronze at the time (which was the late 18th and early 19th century, during the Edo period in Japan). As a young boy, Hokusai was adopted by his uncle, Nakajima Ise. His uncle intended to train Hokusai to become a mirror polisher too. Although Hokusai did not end up following this profession (we can tell that he went another direction by the time he was a teenager), the exposure to his uncle’s line of work caused “reflections, refractions, lenses, and optical effects [to become] a huge part of Hokusai’s work.”1

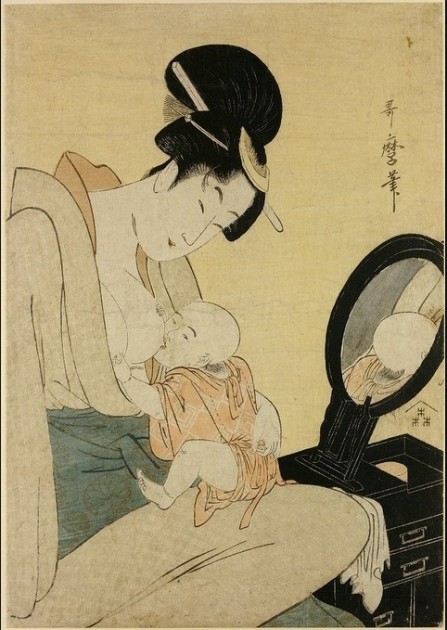

This comment in the podcast made me decide to look and see what examples I could find of mirrors and reflections in Hokusai prints. One of the more popular examples available online is Woman Looking at Herself in a Mirror (shown above). However, in my research I have found that the other ukiyo-e print maker, Kitagawa Utamaro, also made a lot of prints which depict women looking in mirrors (see one example directly below). I assume, then, that Hokusai was not only influenced by his background and uncle’s profession, but also by his contemporaries who were producing similar subject matter in their art.

Kitagawa Utamaro, “Woman Before a Mirror” (also called “Beauty at Her Toilet”), c. 1790. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

In fact, Mara Miller connects the idea of reflections to the production of ukiyo-e prints as a whole: “Ukiyo-e artists thematized perception in countless ways; they were fascinated with the instruments (mirrors, telescopes, and eyeglasses) and the phenomena of perception as a process — lantern light and fireflies and moonlight, mist and shadows and veils. They were fascinated with the act of looking.”2

It is interesting to me how the use of mirrors in these images can play with the ideas of Subjecthood and Objecthood. Do the mirrors make the subjects seem more tantalizing to a (male) viewer, or do the mirrors give more subjecthood to the women who are portrayed (since they are actively engaged in looking)? Mara Miller thinks that the women in these images “assume the right to gaze” at themselves: they employ the power to turn themselves (as subjects) into objects for their own gaze.3

There are lots of examples of reflections and optical effects in ukiyo-e prints, and I thought I’d include some of my favorites below. I especially like these images, because they make me think of how ukiyo-e prints must have influence by the reflections and mirrors that Mary Cassatt depicted in her own paintings, such as Mother Combing Her Child’s Hair (1879), Mother and Child (1900), The Mirror (c. 1905), Woman At Her Toilette (1909).

This print especially reminds me of Cassatt’s Mother and Child (1900), since the baby’s head is slightly visible in the mirror, similar to how Cassatt paints the reflection of little baby buttocks in her mirror!

Utagawa Toyohiro (1773-1828), Daruma Looking in a Mirror at the Reflection of a Woman behind Him, late-18th or early-19th century

Hokusai, Reflection in Lake at Misaka in Kai Province, from the series “Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji,” ca. 1830-32. Woodblock print.

If you have a favorite ukiyo-e print (or Mary Cassatt painting!) with mirrors or optical effects that I did not include, please share and comment below!

1 Holly Frye and Tracy V. Wilson, “Hokusai,” podcast from Stuff You Missed in History Class (quote found approx. 7:30 into recording). Accessed August 18, 2015. Available online HERE.

2 Mara Miller, “Art and the Construction of Self and Subject in Japan,” in Self as Image in Asian Theory and Practice by Roger T. Ames, Thomas P. Kasulis, Wimal Dissanayake, eds. (Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 1988), p. 444. Available online HERE.

3 Ibid., 445. Available online HERE.