Tuesday, December 19th, 2017

Frank Sinatra’s Paintings

I read recently that the Renaissance sculptor Benvenuto Cellini reminded Tony Bennett so much of Frank Sinatra that Tony once gave Frank a copy of The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini as a birthday gift. I scoffed and chuckled a little bit when learning this, since Cellini had a flair for extreme drama. However, Tony said that he admired how “Benvenuto would draw his sword and battle every hypocrite and phony who stood in the way of truth,” and it is this aspect of Cellini that reminded him of Sinatra.1 And although Tony Bennett wrote that he was thinking of Frank Sinatra’s character when he made this gift, this anecdote made me wonder if Frank had more direct connections to the world of visual art. And he does!

The title of this post actually has dual meaning, since Frank Sinatra had a collection of paintings and also was a painter himself! I haven’t been able to find information on his personal art collection (or identify the painters/paintings shown in the Getty photograph linked above), so unfortunately I can’t explore his connection to art as a collector. If anyone knows information about Sinatra’s collection or his collecting habits, please share!

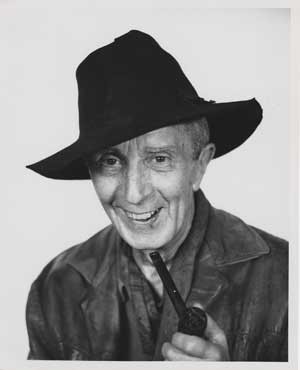

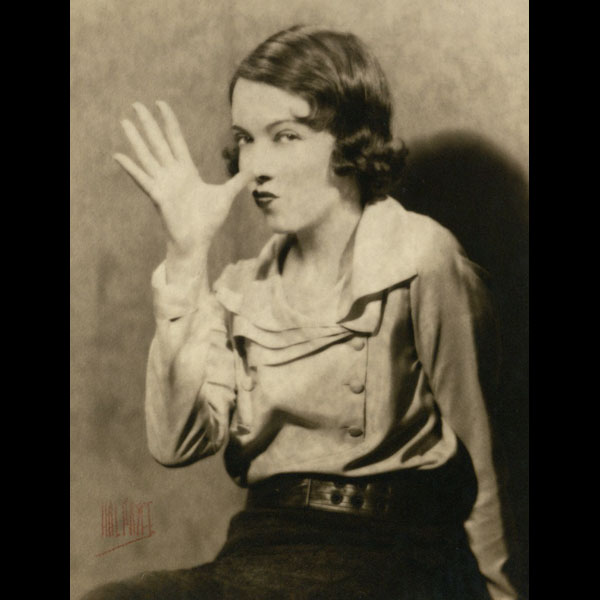

Frank Sinatra in his studio with granddaughter Amanda (left, n.d.), display of Frank Sinatra’s art at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles (right)

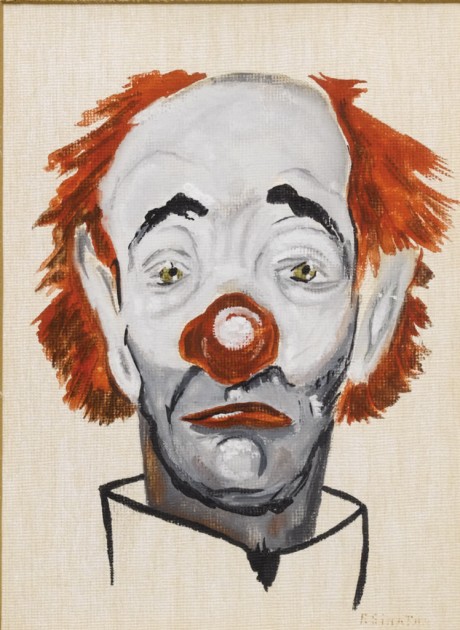

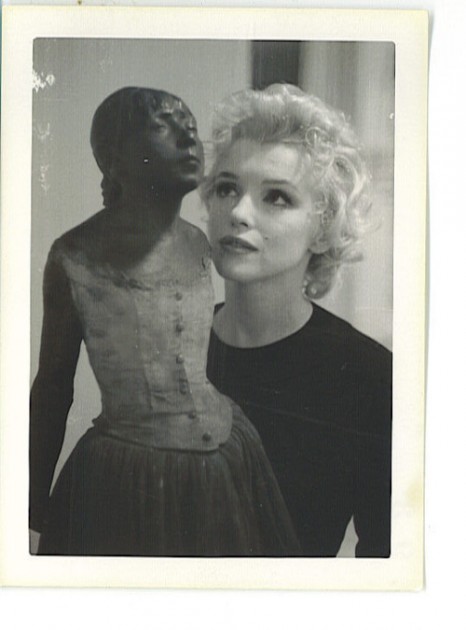

What I have been able to learn, however, is more about Frank Sinatra’s personal interest in oil painting; this was a hobby that he maintained for more than forty years! Some of Frank Sinatra’s paintings and memorabilia are available for sale on a website that is maintained by a collector, and other paintings are on public display at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles (shown in the image above). I also came across a Telegraph article from 2009 which explains how one of Frank’s paintings is believed to have been painted in 1957, during the artist’s difficult divorce from the actress Ava Gardner. The painting is a self-portrait of the artist as a melancholic clown (see below), and it was a subject that he painted again and again and again (and these links are just a few examples!).

No doubt when Stephen Sondheim’s 1973 song “Send In the Clowns” was covered by Frank that same year, this song must have had very special meaning for Frank due to his relationship with Ava and also his clown paintings from the previous decade and a half. In fact, Frank once prefaced his performance of this song with an explanation that this is a breakup song between two adults, and I can’t help but think that Frank pulled from his own experiences with breakups to convey the sentiment of the song. I have a feeling that he thought about his self-portraits as a clown while he sang.

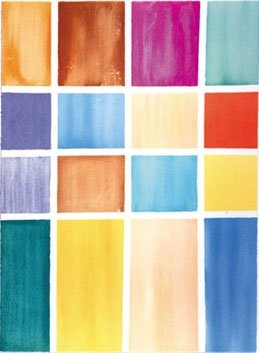

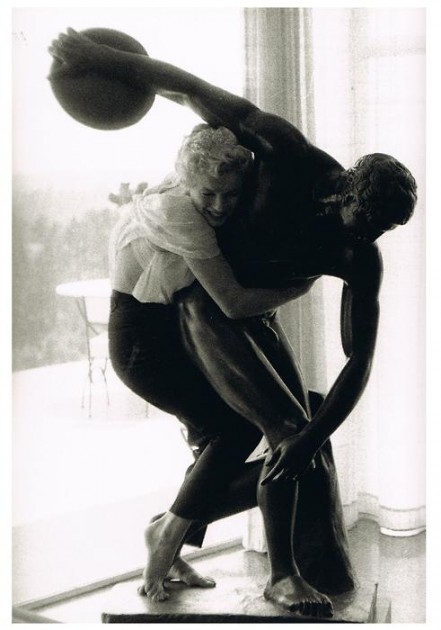

Frank didn’t just create representational art, however. In fact, most of his paintings were heavily, heavily influenced by painters of the mid-20th century, especially the Abstract Expressionists. I recently came across the book A Man and His Art: Frank Sinatra with a forward written by his daughter Tina Sinatra. The book mostly includes color plates of Frank’s paintings, and it’s fun to play a guessing game and figure out what artist and/or painting might have served as inspiration for Frank’s art. For example, easy to see how this painting below is reminiscent of Ellsworth Kelly’s art, for example. The different gradients of opacity and transparency of the pigment remind me a little bit of Mark Rothko.

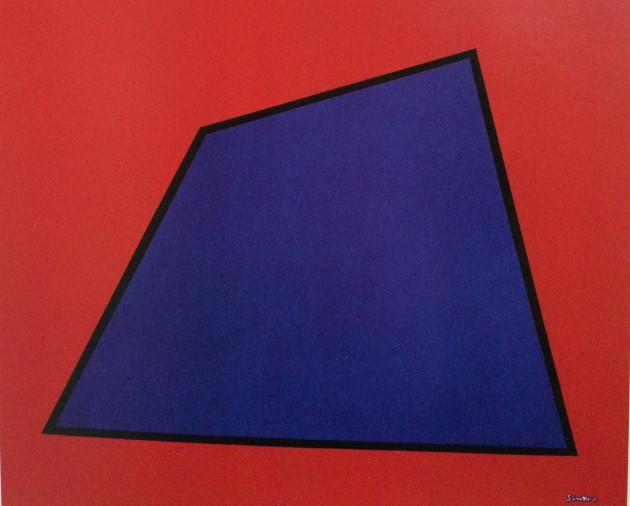

And this bold painting of a geometric shape, which I quite like, reminds me of Frank Stella:

When flipping through A Man and His Art, I also notice paintings that reminded me of Josef Albers, Robert Motherwell, and Franz Klein. I also read a short online article that Robert Mangold’s art also served as an inspiration for Sinatra. And while, like Sinatra, I admire all of these 20th-century artists, I don’t think that Sinatra’s art rivaled these other painters. I think some of his paintings are quite terrible, actually, not because it is derivative of another source but that the colors seem muddied and the brushwork is sloppy.

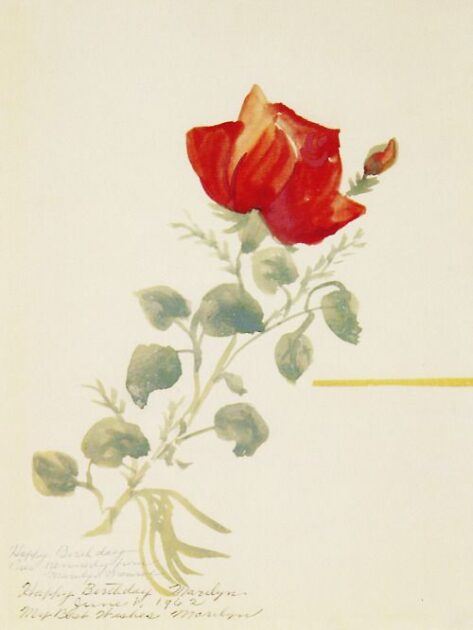

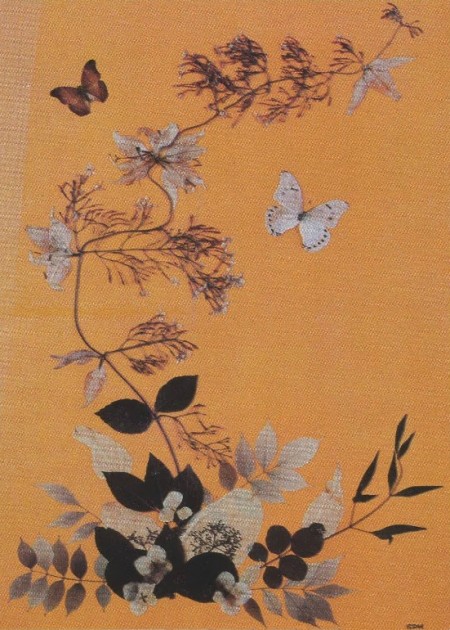

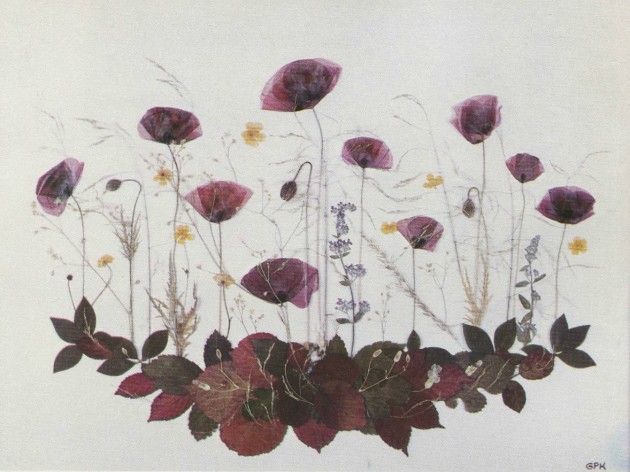

Some of Frank’s art seems more unique to me (although it could just be that I am not familiar with the original source!). Even though I don’t think that Frank was a fabulous painter, but I do really like this one, especially because of the dynamic shapes and lines used to create the stems and leaves of the flowers:

So looking at these paintings by Frank Sinatra, many of which are clearly derivative of other painters’ styles, makes me reflect back on Tony Bennett’s quote about how he thinks of Frank Sinatra as someone who “would…battle every hypocrite and phony who stood in the way of truth.” I don’t think that Frank saw himself as a “phony” when he heavily took inspiration from other artists, both in painting and also in singing. Tina Sinatra makes an interesting point that her dad “was the first to admit that he mimics what he’s seen, but, just as with music, it becomes Frank Sinatra’s because he stylizes it.”2

I like this idea, because I like to think about how Frank Sinatra learned about the potential of crooning and singing softly into a microphone from his slightly-older predecessor Bing Crosby. And Frank took those basic aspects of family-man Crosby’s singing approach and then turned crooning into something sultry. Similarly, since Frank picked up Abstract Expressionism later on in life (especially in the 1980s, after the height of Abstract Expressionism ), he looked to visual art “predecessors” to explore the potential of visual expression. Although I still prefer the Abstract Expressionists over the paintings made by Frank Sinatra (I’m glad you didn’t quit your day job, Frank!), I can see how his work (like by combining the aesthetic of Ellsworth Kelly and Mark Rothko in a single painting) creates something new.

What do you think of Frank Sinatra’s art? Does his art remind you of his music?

1 Tony Bennett, “Sinatra” in Sinatra at 100 in LIFE special edition by Robert Sullivan and editors of LIFE, vol. 15, no. 18, November 27, 2015, p. 9.

2 Tina Sinatra, A Man and His Art: Frank Sinatra (New York: Random House, Inc., 1991), ix.