Tuesday, January 19th, 2016

Parrots in Art

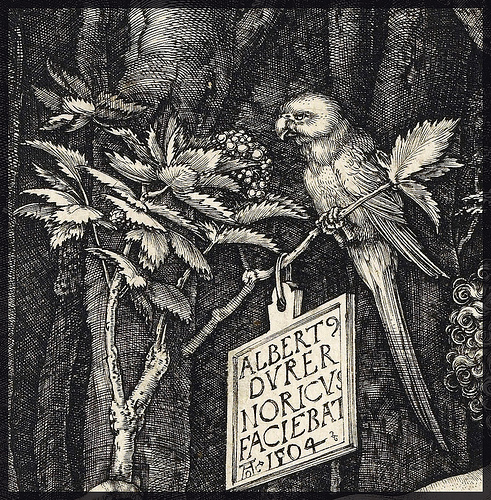

Last week, while driving to work, I was thinking about Dürer’s engraving Adam and Eve, which includes a parrot in the upper left quadrant of the print. In this particular context, the parrot functions as a symbol for the Virgin Mary. The symbolic association might seem like a stretch today, but the belief was that the parrot was similar to Mary. Both the parrot and the Virgin were associated with typically-improbable situations: if a parrot can be taught to speak, then a virgin can become pregnant and give birth! Additionally, there are connections between parrots and Mary’s purity and virginity, which are explained in more detail elsewhere. Here are a couple of my favorite representations of the Virgin with parrots:

Jan Van Eyck, detail of parrot from “Madonna with the Canon van der Paele,” 1436. Oil on wood, 122 x 157 cm

I think that the association with the Virgin and parrots is one reason why there are so many paintings of women and parrots in comparatively recent centuries. Parrots typically don’t appear with men in art (perhaps because pirates didn’t commission their own portraits? Ha ha!). However, I do know of one example of a man depicted with parrots:

Typically, though, in art parrots are usually depicted with women, or appear in a still-life painting, or in some type of naturalist or scientific drawing. Why is this? The scientific examples are easily explained, since parrots are non-European and therefore served as an example worthy of study. In addition, parrots could be studied by artists in relation to their anatomy and color. Such was the case with Van Gogh, who studied the anatomy of a stuffed parrot when he created The Green Parrot:

Here is one example of a parrot in a still-life painting, although there are several others by this same artist Georg Flegel (see Still Life with Pygmy Parrot and Dessert Still Life):

I think that the inclusion of parrots with still-life paintings is interesting, because it connect parrots to the material world, wealth, and trade. As an exotic creature from non-European lands, parrots were highly prized during the colonial period. And it wasn’t just the live birds that were valued: in the colonial era the plucked feathers of parrots were valued too. In Mexico, the indigenous practice of feather painting was combined with European pictorial conventions (see below). This type of feather painting was highly prized by the Europeans, which adds to how parrots were connected with material value.

Beyond these examples, there are lots of representations of women with parrots. In this context, I think there is more symbolic and visual meaning at play than a mere historical connection to traditional representations of the Virgin. For example, as late as the 17th century, a connection between women and caged birds was made in moralizing paintings suggesting seduction (such as Couple with Parrot (1668) by Pieter de Hooch.) Also, the brightly-colored and and textural plumage of parrots are very decorative, and this is a key thing to remember in relation to representations of women. As a result, parrots complement decorative elements within a work of art, and give an added sense to materiality to such paintings which are dedicated to showing pretty objects. The inclusion of the parrot hints that the other objects in the painting (whether a female figure or fancy tableware in a still life, for example), are especially meant-to-be-looked-at by the viewer.

The depiction of a parrot with a woman hints that the woman is also decorative, like the parrot, and perhaps is even exotic. I think that there might even be a correlation with the softness of the bird’s plumage and the implied softness of the female skin, especially with nude/semi-nude paintings like Delacroix’s Woman with a Parrot and Tiepolo’s Woman with a Parrot. Even the more muted of paintings that completely cover the female body still hint at an element of decoration and texture, especially with the silky intimate dressing gown that is worn by Manet’s model in this painting:1

It seems to me that the usage of parrots in art took a vast turn from their symbolic connection to Mary (stressing the miraculous nature of the virgin birth!) to the tangible, decorative, and perhaps even frivolous associations with parrots in later art. What do you think? Do you know of any other genres or scenarios in which parrots appear in art?

1 Recent scholars have interpreted Manet’s painting as an allegory for the five senses. In this context, the parrot (as a confidant) may represent hearing. For more information see: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/89.21.3/

Excellent stuff! I have seen plenty of parrots throughout art history and never once stopped to think what symbolism was being invoked. But anything colourful and exotic could have been included happily in religious and other art… why not?

My biggest question involves the inclusion of parrots with still-life paintings, one of my all-time favourite art genres. It may well have connected parrots to the material world of wealth and trade, but I wonder how many families who bought paintings… had ever seen a live parrot in their lives.

Love the Max Slevogt, “Man with Parrots,” 1901 impressionist painting with parrots hanging off the man’s pockets. As a parrot person I know exactly how he feels.

Hi Hels! Thanks for your thoughtful comment. Your question about live parrots prompted me to do a little bit more research, and I’ve been reading the fascinating book, “The Parrot in Art: From Dürer to Elizabeth Butterworth” by Richard Verdi. This book has a whole section that is dedicated to parrots as pets, and explains that parrots were popular household pets of the Dutch upper middle class in the seventeenth century (p. 23). It seems likely to me, then that many people had seen parrots in Holland, particularly those who were able to afford to buy art. Verdi writes, “Imported into the Netherlands from the country’s trading expeditions to Brazil and the Far East, parrots feature more prominently in the history of art in Dutch domestic genre scenes than in any other category of painting” (p. 23). Interestingly, even some artists owned parrots, including Jan Steen. His pet Scarlet Macaw is featured in the painting that depicts himself and his family (“As The Old Sing, So Pipe the Young”).

As a child my mother had the annoying habit of leaning out the back door and yelling my first and middle name whenever she decided it was time for me to come home. Chico, the parrot next door, was excellent at yelling my name exactly like my mother, and worst when he’d see me coming he’d start laughing his head off.

Dam I like that bird. He bit too.

what he wants to convey through this painting?