Thursday, October 30th, 2014

“Almost Repellant” Monsters

Happy Halloween! Tonight I’ve been perusing through an interactive website hosted by the MoMA about the artist Odilon Redon. Given this Halloween season, I’ve particularly enjoyed looking at the “Monsters” section. These lithographs are based off of the charcoal drawings that Redon called his “noirs” (“black things”). Redon made lots of these charcoal drawings. In fact, he worked almost exclusively in black and white until he was about fifty years old! (You can read more about Redon’s “noirs” HERE.)

One of the publications that is highlighted in the MoMA interactive site is Marina van Zuylen’s chapter “The Secret of Monsters” (read online HERE) in Beyond the Visible: The Art of Odilon Redon. I really like that van Zuylen writes, “Redon’s genius is to make his figures almost repellant. He rescues them from radical ugliness by endowing each of them with traits that produces empathy.”1

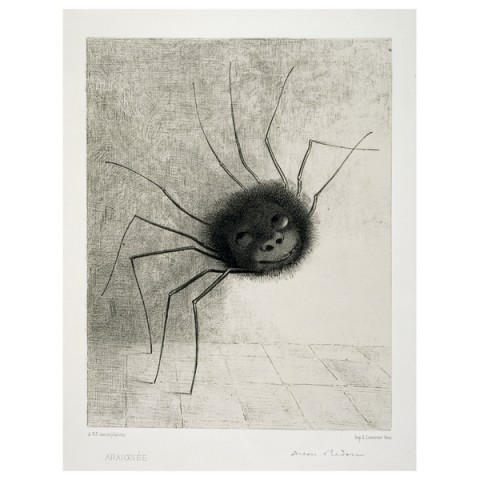

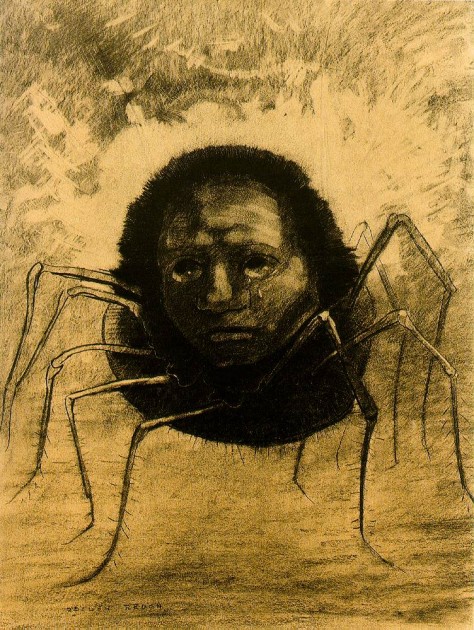

I think this is such a great point, because Redon makes his monsters slightly relatable or understandable in terms of human emotion, as is the case with his lithograph Smiling Spider (1887, see above; also see another printed version from 1891). Another example would be The Crying Spider (1881, see below). This example seems especially poignant to me in terms of evoking empathy, since the spider stares directly at the viewer with large, round eyes. For me, it is these types of empathy-evoking features which make these drawings and other similar ones by Redon simultaneously compelling and disconcerting.

As I’ve been looking at Redon’s drawings tonight, I’ve thought about another work of art that is both compelling and disconcerting. In this instance, though, the “monsters” are the countless skeletons that appear in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Triumph of Death (c. 1562, click on hyperlink to see high-resolution details). This painting is dominated by an army of skeletons who wreak all sorts of havoc across a barren landscape. Peasants and rulers alike are downtrodden, captured, or killed by these skeletons, thereby emphasizing the transience of life and inevitability of death to all mortals.

Despite the unsettling subject matter, this painting contains an overwhelming amount of fine detail, which is very compelling and captivating from a visual standpoint. Additionally, Bruegel includes a lot of small, humorous details which make these skeletons seem especially disconcerting, because they evoke an element of empathy or relatability that resonates with the viewer. Many of the activities are recognizable and suggest human emotion: one skeleton sits with his skull leaning into his hand, as if resting or thinking. Another skeleton nearby plays the hurdy-gurdy (see detail below).

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, detail from “The Triumph of Death,” c. 1562. Oil on panel, 117 cm × 162 cm (46 in × 63.8 in). Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Additionally, other skeletons are chasing women or donning pieces of contemporary 16th century clothing, both of which suggest an element of relatability in terms of human desire and culture. Another detail shows a skeleton who assumes the same slumped body position as the mortal whom he is killing or accosting, suggesting to me a reminder that these skeletons were once living mortals themselves.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, detail from “The Triumph of Death,” c. 1562. Oil on panel, 117 cm × 162 cm (46 in × 63.8 in). Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, detail from “The Triumph of Death,” c. 1562. Oil on panel, 117 cm × 162 cm (46 in × 63.8 in). Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Although Redon and Bruegel are very different in their aesthetics, I think that they both are attempting to depict something that is “almost repellant,” in terms of appearance and/or concept. But there is something that is relatable and can resonate with the viewer in both of these instances, which is perhaps why these paintings have been labeled as “disturbing” and creepy.

Can you think of any other disturbing works of art that are “almost repellant” because they evoke empathy or are relatable to you?

1 Marina van Zuylen, “The Secret Life of Monsters,” in Beyond the Visible: The Art of Odilon Redon by Jodi Hauptman, ed. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art: 2005), 60. Also available online: http://books.google.com/books?id=4DYjsCbZNJsC&lpg=PT31&ots=auheV2K2A9&dq=redon%20smiling%20spider%201887&pg=PT31#v=onepage&q&f=false

“In fact, he worked almost exclusively in black and white until he was about fifty years old!”

Mind officially blown!

I have always liked Bruegel’s work, but this is a really interesting perspective on the Triumph of Death. He certainly brings out the humanity in the skeletons, as if they were grisly cartoon characters in a Halloween world, but it really brings death to life. It reminds me of Durer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, which I feel is a poignant personification four terrible evils. In some ways, it seems to highlight the monsters within ourselves.