Sunday, September 21st, 2014

Book Review: “The Horses of St Mark’s: A Story of Triumph in Byzantium, Paris and Venice”

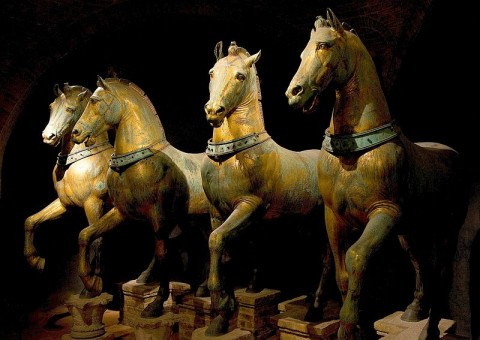

Replica quadriga (four horses) of Saint Mark’s, Venice, late 20th century (after originals probably from the 2nd to 4th centuries CE)

I visited St. Mark’s in Venice on a study abroad over ten years ago, but I don’t remember much about my experience. The basilica itself was undergoing some major renovation, and my impression of the interior revolved more around scaffolding than mosaics. I remember seeing the porphyry portraits of the tetrarchs on the exterior, but I don’t remember seeing the replica sculptures of horses (see above) at Saint Mark’s (located above the main portal). I also don’t remember seeing the original horses (shown below in the basilica museum). In fact, the horses of Saint Mark’s never caught my attention in any type of book or article until I received a copy of The Horses of Saint Mark’s: A Story of Triumph in Byzantium, Paris and Venice by Charles Freeman.

I really liked learning about the horses and their “biography” over the centuries as I read this book, but I have to admit that the chapters dealing with the political history of Venice were rather dull to me. It almost felt like Freeman was trying to bulk up material for his book by adding in extra information about Venice, which wasn’t quite pertinent to the story of the horses.

Despite the sections of this book that I found dull, I really enjoyed reading several sections of it. These horses have a very complex history and are unique in several ways. Here are a few other things enjoyed learning in this book:

Original quadriga (Four Horses) of Saint Mark’s, probably 2nd to 4th centuries CE. Image courtesy Wikipedia

- These horses were probably made in the late Roman period. Freeman thinks that they may have been created as a crowning sculpture to a triumphal arch, since quadrigae were often depicted pulling a god or hero (such as an emperor) in a chariot. Freeman thinks that these horses may have appeared on a triumphal arch commemorating Septimius Severus’s victory over Byzantium in 195 CE.1

- Chariot races and horses (and therefore sculptures of quadrigae, by extension) are associated with triumph and power in Greco-Roman culture. Originally, chariots were seen as synonymous with the power of the gods, but Roman emperors became associated with this symbol of power since the hippodrome/circus was a public venue where the emperor could be physically seen by his people and also display imperial power through ceremonies.2

- These horses are very unusual, given that they are made almost entirely in copper. The mixture is about 98% copper, 1% tin and 1% lead. Typically, bronze contains about 10% of tin-and-lead mixtures, although sometimes as high as 20%.3 Copper has a higher melting point than bronze, so when it comes to casting, these large-scale horses are the product of great technical feats.

- Originally, these sculptures were also gilt, and Freeman thinks that these horses were intentionally cast in copper so that the gold layers would adhere properly to the surface. These horses appear to have been gilt with a method which involves mercury, a substance which reacts with tin and lead; the mercury method can’t be used successfully if one is gilding with regular bronze.4 I’m sure these horses would have been very striking back in the day, especially if they were gilt and displayed outdoors!

- These horses have traveled a lot over the centuries. We know they were located in Constantinople, and probably were located at the hippodrome or the Milion, an imperial building that was located outside the hippodrome but near its starting gates. The horses were likely brought to the hippodrome or Milion from some other monument too, such as the Septimus Severus arch that Freeman proposes.5 From Constantinople, the horses then were brought to Venice in the Fourth Crusade of 1204, after Constantinople was sacked. The horses were removed from the façade of St. Mark’s in December 1797 by orders of Napoleon, and from there were taken to Paris. While in Paris, the horses decorated the gates of the Tuileries Palace and then later on a triumphal arch dedicated to Napoleon (Arc du Carrousel) in the front of the Tuileries.6

- The intervention of the Venetian sculptor Antonio Canova led to the return of these horses to Venice after Napoleon’s downfall in 1815. The horses were taken down in September of 1815 and arrived in Venice in December of that same year.7 After an exhibition in the early 1980s, in which one of the horses starred as the main attraction, all four original horses were placed inside Saint Mark’s in 1983 in an effort to preserve the sculptures against the adverse effects of pollution.8

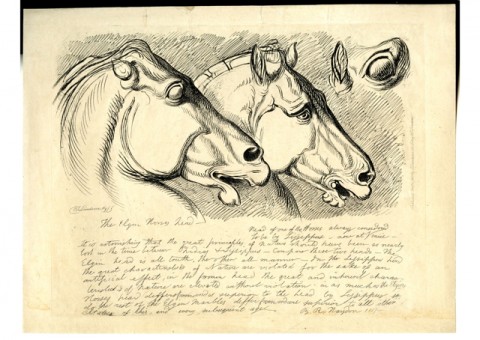

- The horses of Saint Mark’s have been often assessed in terms of their aesthetic quality. When the Parthenon Marbles caused a sensation in the 19th century after their arrival and display in England, British artist Benjamin Haydon drew a sketch to compare the Parthenon horse (from Selene’s chariot) with one of the horses of Saint Mark’s (see below). In this drawing, Haydon aimed to show the superiority of the Parthenon sculpture over that of horse from Saint Mark’s. Haydon found that the eyes of the Saint Mark’s horses were not true to life; he argued that they were too sunken in appearance to be realistic or plausible. He also wrote that the nostrils “of the Venetian horses seem wrongly placed, the upper lip does not project enough and there is an evident grin as [if it] had the snarling muscles of a carnivorous animal. . . it looks swollen and puffed as if it had the dropsy.”9

Landseer. etching after Benjamin Haydon’s 1819 drawing “Study Of The Horse’s Head From The East Pediment Of The Parthenon And Of The Head Of One Of The Horses Of St Mark’s Basilica, Venice.”

I think that these horses probably have one of the most complex known biographies within Western art history. Like many objects that are displaced and transported throughout their symbolic lives, these horses often were moved as a result of war and conquest. I’m glad that these horses have been able to remain intact over the centuries, despite their propensity to travel!

1 Charles Freeman, The Horses of St. Mark’s: A Story of Triumph in Byzantium, Paris and Venice (New York: The Overlook Press, 2004), 296.

2 Ibid., 63-65.

3 Ibid., 263.

4 Ibid., 265.

5 For a discussion of other possible locations of the horses, specifically the original location (besides the Septimus Severus arch theory) and the later location after the transformation of Constantinople by Constantine, see Ibid., 29-31, 89-91.

6 Ibid., 201-205.

7 Ibid., 219-220, 223-224.

8 Ibid., 254-255.

9 Ibid., 231-232.