Tuesday, March 11th, 2014

Marshes in Ancient Egyptian Art

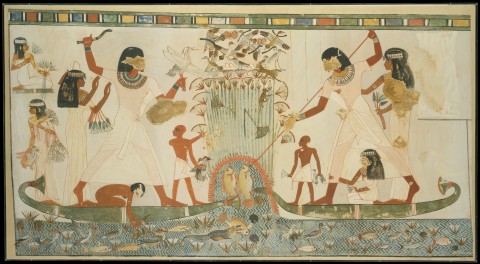

Marsh Scene, Tomb of Menna, 1924, facsimile of original from ca. 1400-1352 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art

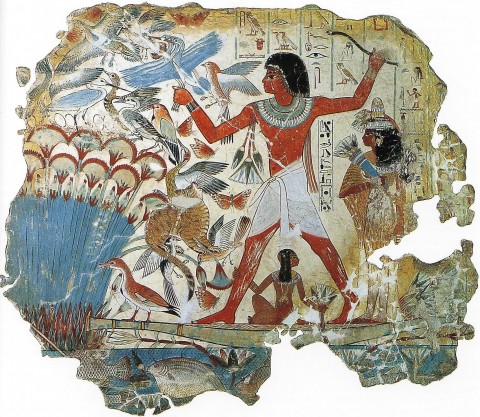

Tonight I stumbled across some interesting information which has caused me to think more deeply about the reason why marsh scenes sometimes appear in Egyptian tomb imagery. To be honest, when I previously have considered these types of scenes (the most famous one being the “Fowling Scene” from the Tomb of Nebamun, shown below), I have usually thought more about the act of hunting than the marsh setting itself. Perhaps I’ve taken marshes for granted in Egyptian culture, since I know that they are located along the Nile. However, the marsh setting has a lot of symbolic associations in ancient Egyptian culture and mythology, most notably with life and resurrection.

There are several reasons why marshes are connected with life and resurrection in Egyptian culture. In the creation mythology for the ancient Egyptians, life was first formed out of the primeval waters of chaos (Nun), creating a primeval marsh and mound of fertile earth (the latter is sometimes referred to as the benben, due to the benben stone at Heliopolis which represented this primeval mound). Marshes, therefore, were a reference to creation and life. In the case of the two images that I have included in this post, the tomb owners Menna and Nebamun draw parallels between their hope for rebirth in the afterlife and the original birth of the world by depicting themselves within a marsh.

Additionally, marshes were also significant in Egyptian mythology because Isis helped to prepared her husband Osiris’s body for resurrection by hiding his coffin in a marsh.1 Later, Osiris’s evil brother Seth stumbled upon the casket and tore Osiris’s corpse into various pieces (the number of pieces vary in accounts, ranging from fourteen to forty-two). Isis searched for each of the pieces and buried each at the place where it was found.2 Later, Osiris resurrects: the dismembered body comes together to form the first mummy.

There are many other elements within marshes that also have symbolic associations with life and resurrection, most notably the papyrus and lotus plants. In both of these images, Menna and Nebamun hunt birds that are found in a thicket of papyrus. The thicket of papyrus also might be a reference to the mother-goddess Hathor, who sometimes appeared as a cow in a similar thicket of papyrus (see one such example from the Papyrus of Ani).3 Hathor, who is associated with motherhood and fertility (among other things) reinforces the symbolic associations between papyrus, the marsh, and life in this context.

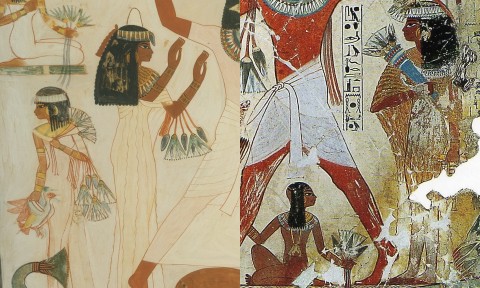

Detail images of family members holding lotus blossoms from tomb of Menna (left) and tomb of Nebamun (right)

In both of these scenes, the family members of Menna and Nebamun hold lotus blossoms in their hands. The lotus has several associations with death and rebirth. For example, the lotus blossom sinks underwater at night, only to reemerge out of the water and bloom during the day. It was also believed that a giant lotus blossom came out of the primeval waters of Nun, out of which emerged the sun-god. The Book of the Dead also included a spell to transform someone into a lotus, which would ensure the promise of rebirth to the deceased.4

Do you know of any other symbolic associations with marshes in Egyptian culture? Do you know of any other Egyptian fowling scenes that are set in marshes? I know that marsh imagery also appears in other contexts as well, such as the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak. There, the capitals of the columns are decorated with lotus and papyrus blossoms. Considering the number of columns that appear in that vast hall, I’m sure that ancient Egyptians within that space felt very much like they were in a marsh thicket. Within that sacred space, I imagine that the symbolic associations with the marsh would have been very clearly understood.

POSTSCRIPT: There are a few more things that I want to add about these two hunting scenes, just so I can remember them in the future!

- “The act of throwing a throwstick in ancient Egyptian is qema, for the Egyptians this would recall the word qema meaning ‘to create’ or ‘to beget.’ In the same way the word for spearing fish is set, which resembles another word seti meaning ‘to impregnate.’ Through these puns the actions of the tomb owner can be read as having meanings appropriate to rebirth.”5 I think it is interesting to note that both Menna and Nebamun’s powerful poses recall the similar raised arm of Narmer in the Palette of Narmer, which was created about 1,650 years before!

- The wild birds in these scenes represent chaos. By hunting these birds, the male figure is restoring order. In this sense, the men are equating themselves with Osiris. Unsurprisingly, fowling is one of the activities of Osiris, who triumphed over chaos by defeating his evil brother Seth.

- Both Menna and Nebamun are shown as youthful, energetic figures. This suggests that both men hope to have a similar, youthful forms in the eternities. I’ve always associated youthful idealism with the Greeks up until this point, but I can see that youth was also favored by the Egyptians too. Could it be that the Greeks were influenced by Egyptian thought in this regard?

1 Mark Getlein, Living with Art, 10th edition (New York: Mc-Graw HIll, 2013), 331.

2 For more information on the Osiris and Isis mythology, see Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, The Princeton Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 238-239.

3 Gay Robertson, Women in Ancient Egypt (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), 188. Text available online here: http://books.google.com/books?id=UTSA88SVHCMC&lpg=PA188&ots=lC2k15W4SO&dq=symbolism%20of%20marsh%20%22ancient%20egypt%22&pg=PA188#v=onepage&q&f=false

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

Have you read Symbol & Magic in Egyptian Art by Richard H. Wilkinson? It’s really good. I believe it’s from that book I learned Egyptian temples themselves are actually symbolic recreations of the birth of creation, with the hypostyle halls filled with djed pillars representing Nun.

Thank you for posting this. I remember some years ago having to wade through hoards of camera snappers at the British Museum trying to view the fragments of the tomb of Nebamun for part of my degree. Three weeks later I was in Avignon at the Calvet museum. I had the whole Egyptian section to myself and was able to view their fragment of the tomb at my leisure.

Hello, Patsy! Thank you for your comment. I didn’t realize that there was a fragment from the tomb of Nebamun in Avignon. I looked up more information about that fragment after reading your comment. If anyone is interested, you can see the Musée Calvet fragment here:

http://www.musee-calvet.org/beaux-arts-archeologie/fr/oeuvre/fragment-de-paroi-de-la-chapelle-funeraire-de-nebamon

The Calvet museum also owns a stele from the tomb of Nebamun:

http://www.musee-calvet.org/beaux-arts-archeologie/fr/oeuvre/stele-de-nebamon-gouverneur-du-fleuve

Hi heidenkind! Thanks for your comment! I’ll look into the “Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art” book by Wilkinson. Thanks for the recommendation. I’d love to learn more about djed pillars, anyway. I once read that they symbolize the spine of Osiris. It would be interesting to find more connections between these pillars and Nun.