Wednesday, July 31st, 2013

Lavinia Fontana’s Self-Portrait and Gender

Lavinia Fontana’s self-portrait from 1579 has long been of interest to me. I wrote about this painting on a guest post at Three Pipe Problem a few years ago, and I regularly use this self-portrait when I discuss Renaissance art with my students. Today I read some new considerations about this portrait in relation to gender and objectification, which I thought that I would jot down. These ideas were discussed by Catherine King in “Portrait of the Artist as a Woman” in Gender and Art (edited by Gill Perry).

I think King has some great ideas, and I think that a few of them can be taken even further. For example, King mentions that the circular form (tondo) form for the painting is significant, since “the circle was regarded as the most perfect geometric structure in contemporary scientific and philosophical thought, as it described the path of the planets and the structure of the cosmos.”1 I also wonder if Fontana chose this particular form because the circle is associated with the female sex, as was the case in ancient cultures like those of Egypt and Rome. The circle, for example, recalls the shape of the maternal womb and also the ovum. We know that Fontana’s self-portrait was intended to be placed in an engraved collection of other portraits, and it would be interesting to know if any of them appear in tondo form. (Does anyone know? I do know that the engraved collection was never published, but I’m not familiar with other original extant paintings that were intended to be turned into engravings for the collection, beyond this self-portrait).

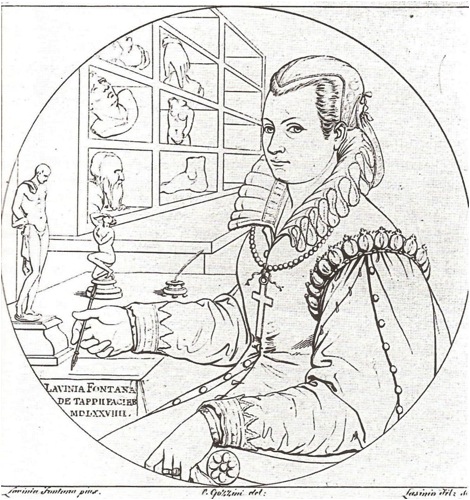

19th century engraving of Lavinia Fontana's Self-Portrait, Castello Sforzesca, Raccolta Bertarelli, Milan

Catherine King also mentioned a few other significant details which I have not considered before. A nineteenth century engraving of this portrait allows us to clearly see that a nude male anatomical model is placed in the foreground, while a female nude is placed in the middle ground. On one hand, Fontana includes these figures to show off her education; she is a learned artist who has studied the human form and anatomy. However, Fontana may have also composed these figurines in a way to control her own image in relation to social decorum. King points out that the male figurine is turned with his head downward, so “there is no risk of the viewer imagining the naked man looking at [Fontana] while she is looking at us. It is, rather, she who is in charge of the gaze.”2

I think we could also take King’s ideas further and say that Fontana seems to want to control the (male) gaze and objectification of the female form in other ways, too. One can see that the little female anatomical model is twisted in a way so that her left thigh blocks the viewer from seeing her genitals. Her arm also reaches upward, partially covering her breast from view.3 Just as Fontana has worn high-collared and modest clothing in this self-portrait, she also seems to eschew objectification of the female nude, through the figure’s placement further away from the viewer and composition of the figure’s limbs. King hints at something along these lines, too: she notes that the female figure is placed further in the background in order to discourage the viewer from “mentally undressing” Fontana herself.4

King also finds that Fontana asserts her control over her image and female representation by drawing a contrast with the anatomical casts that are in the background. These casts, which are arranged in a cabinet, are also gendered. For example, three male heads are included in the shelves closest to the viewer. The heads and other (possibly male) body parts are therefore objectified through their fragmentation. Therefore, it seems like Fontana is stressing the male objectification in order to emphasize her subjecthood as the female portrait sitter. And although King never states this opinion outright, one gets the sense that King finds the fragmented bodies to be a bit threatening to the (male) viewer. (It’s not difficult for me to see how a modern viewer/reader could make some loose associations with Freud and castration theories!)

All this being said, I’m interested to know what you think of Fontana’s portrait. Does she seem intimidating and/or controlling to you? Do you feel like Fontana is trying to showcase her beauty and physical appearance? Can you think of any other ways that this painting can be interpreted in terms of gender?

1 Catherine King, “Portrait of the Artist as a Woman” in Gender and Art by Gill Perry, ed. (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1999), p. 53.

2 Ibid., 53.

3 The composition of the female figurine reminds me a little bit Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Susanna and the Elders” (1610). In the past several decades, the composition of the figure of Susanna has been interpreted as one who resists sexual objectification (partially due to art historians who were compelled to discuss this painting in relation to Gentileschi’s personal life).

4 King, 53.

The whole “gender” analysis is completely wrong!

This type of portrait is common for the era and it has no gener specific. The 16th century valued erudion, and it saw the birth of the art lovers cabinets and the bith of the art collection. The statues in Fontana’s self-portrait are a comment on the relationship between painting and (Greco-Roman) sculpture, which was then rediscovered). The body-parts in the foreground are) a comment on the relationship between painting and science (see Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo for more on that) and b)a comment on the theme of “Deus pictor”, God as painter, for which she, Fontana the erudit artist which studied human anatomy, now serves as an assistant, in a way (see the signature in the left-wing corner with the latin verb “to make” in imperfect mode “faciebat”, because only God uses the present when he made the world). In short, this is how Fontana potrays herself : as an erudit artist at work in her cabinet, in fact signing her work as we watch her! – Nothing special or gender specific there.

Finally, the shape of the canvas is not related in anyway to the sex of the artist, but to the massive interest in reflection that characterized the arts and the culture of the era, especially when in relation to the new genre of the portrait (reflection was understood as a physical property of mirrors but also as a cultural, philosophical property, as in self-depiction, self-understaning – see Parmigianino’s self-portrait, a masterpiece which illustrates this trend among artists in the late Renaissance, also mentioned by Vasari, of playing and experimenting with reflection – it is, after all, the era when the artist emancipates from crafstman and starts to become the “super-star”, individualised, unique, artist we still, somewhat, know today).

The only slight connexion to gender that can be “read” from Fontana’s self-potrait, it’s more of a religious comment rather than a modern, “gender studies”, comment as people immagine nowadays : the cross on her neck shows that Fontana, the pope’s painter, is a faithful Catholic women, while the position and shape of the two statues, one of a almost naked man standing and another of a Venus-like covered women on her knees, seem like an allegory regarding the proper Christian roles of the man and the women, therefore, I think best – and in line with the artist’s intention and culture of the era – interpretation of Fontana’s self-portrait as that it is a portrait of Fontana as a whoel, of Fontana in her many roles : the erudit artist, the pious Catholic and the good, faithful and loving wife.

I don’t want to sound irritating, but I am a little amazed by the lack of some elementary cultural perspective in American, but also ideologically driven, “Americanized”, new generation European art critics, and by how little respect they can have for the discipline they study – I mean, you are supposed to, at least, first uncover the meaning of a painting, not to read into it the fashionable ideological clichés of the 21st century academia! Sure, there can be different opinions, but there’s a limit on the speculations you can make starting from basic facts verified by historical series. – Do you really believe that 16th century Lavinia Fontana, the pope’s painter, could express her life experience in terms such as “sexual objectification”? Moreover, could or would she express all that in such a conventional – although quite new back then – medium, such as a self-portrait, which might have been critical for her marketing succes? – Everybody can have an opinion, free speech and all that, but art history – as any real scholarly pursuit – is really not a playbacked political morality tale or an ad-hoc activist social history class!

I agree with Bogdan. Gender studies are important but let’s keep in mind Susan Sontag’s ‘Against Interpretation’!

In this context it is interesting to note the fact (not a speculation!) that many women participated as members in the Italian learned academies, 1525-1700. Among them Livinia FONTANA, a member of Accademia di San Luca, Roma.

See for further details the Comments of April 8 and 10, 2013 on my post ‘Women Artists who depicted Aphrodite/Venus (I)’ and the article in The Times Literary Supplement of April 5, 2013 ‘L’Unica – and others, Women and the Italian learned academies, 1525-1700’ by Jane Everson & Lisa Sampson.

http://kbender.blogspot.be/2011/08/women-artists-who-depicted.html?showComment=1375540054676

A better reference than Susan Sontag’s book is the 1436 book of the blog’s patron, Leon Battista Alberti, “De pictura” (“On Painting”). You will notice there that the window, as an image that captures a piece of the world in lines and colours, is his prefered definitional metaphor for the (modern, chevalet) painting, while the mirror is his preferred definitional metaphor for the preeminent mimetic technique of Renaissance, modern, painting – the geometrical perspective, which tries to capture the perfect reflection of nature in art. The portrait was back then a new genre, just a piece of the large window-painting featuring “histories” (scenes with many characters, relihious or secular, with background landscapes, hidden portraits or self-portraits etc) prescribed by the artistic norm of the age. The self-portrait was an even more revolutionnary genre because it was a second degree reflection of nature and thus a reflection (in the sense of meditation) on the art of painting : the artist who mirrors nature and who is consequently outside “the window” by definition now consciously mirrors himself…in the mirror-painting…The painter becomes an actor in his very own play, or, in sociological terms, he turns from an anonymous craftsman as in the Middle Ages into the modern, “brand-name”, artist.

Hello Bogdan. Thank you for taking the time to comment on my post. I also agree that Fontana emphasized her education and erudition through this portrait, a topic that I covered in an earlier post for “Three Pipe Problem” (the link is at the beginning of my post). In this light, her portrait fits squarely among the other portraits of the time, since artists are concerned with associating arts with the liberal arts instead of the mechanical arts.

I am aware of the use of tondo in 16th century portraiture; Fontana was by no means unusual. The Parmigianino self-portrait is a good example. One can see that Parmigianino is concerned with the effects of distortion by mimicking a mirror and painting on a curved piece of wood. I simply wonder if Fontana had other reasoning for choosing the tondo shape, beyond its fashionable use at the time, but I realize that this half-baked idea requires more research. I know that Fontana painted a few portraits for the Dominican scholar Alfonso Ciacón’s collection (including the one highlighted in my post), but I am unaware of their dimensions or shape. If Fontana decided to depict herself in a tondo, whereas the other portraits are square or rectangular in Ciacón’s collection, I would be interested in trying to discover whether the shape had more personal significance for the artist. I know that she painted another tondo soon after this self-portrait, called “Portrait of a Girl” (1580-1583), which also may suggest that she simply liked the shape. I’ll need to do more research to come to more of a conclusion.

You have raised an interesting point about 21st century academia. All historians must try to divorce themselves from their own current mindset as much as possible when trying to uncover the original intention behind a work of art. I personally think that most Renaissance women were concerned about representing themselves in a moral light in portraiture, both female patrons and artists alike. Such moral behavior was emphasized, among other elements, by the modest clothing which covered the bodies of these women. In one self-portrait by Sofonisba Anguissola from about 1556, the artist wore high-collared clothing and also modestly covered her body with a medallion (almost like a shield). Although these women would not have used the term “sexual objectification” (a popular term for 20th and 21st century feminist studies), I feel that the concern for modesty and desire to eschew objectification is very much present in visual and textual evidence. Similar accounts for modesty can be seen in the portraits of wealthy widows who commissioned works of art during the Renaissance period.

Hi K. Bender! Thanks for your comment and the link to your post. Women definitely did depict Venus in their own art, although I am not aware of any female Renaissance artists who depicted themselves as Venus in a self-portrait. If you are familiar with such a representation, I would be interested to know of it!

Fontana was interested in asserting her education and training in this painting. I believe that this 1579 self-portrait was created before the artist joined the Academy in Rome, since she moved to Rome in 1603.

I don’t want to dwell too much on the topic, but I still think you – and especially the writers you cite there – tend to look at things completely backwards, i.e. you are trying to find “gender issues” of the kind 20th century social movements and their ideological writers talk about in Renaissance art, which is really nonsense because you’re not only ignoring the proper historical context but you’re ignoring the art by reducing it completely to a (very reductionist) contemporary pop-ideology!

It’s evident that a portrait of a 16th century “high-society” widow will show a modest, pious, in mourning…well…widow. That’s almost the “classical” definition of a widow, since in strict Catholic practice of the time I think one wasn’t supposed to remarry when the spouse dies. You don’t need a “sexual objectification” theory, feminism or any laccanian or freudian or whatever analysis to understand and interpret that! On the contrary, it’s usually a misunderstanding to view the paintings of those times (and sometimes even the paintings of our times) in these very narrow and ideologically loaded terms, given their complex social function, cultural context and artistic intention! Moreover, art has a social and historial component, but art is always more than social history, and not all societies and histories are alike.

Let’s take a case-study suggested by you.

By looking carefully and without “prejudice” at the context, it makes sense that the young Sofonisba Anguissola, who was then in search for a proper husband – proper for a cultivated painter and Lady at the royal and imperial Court of Spain as she was! – will compose a self-portrait in which she will showcase: a) her origin (Cremona, in the inscription, a city is Lombardy, northern Italy, close to Tuscany, where the tondo form painting and sculpture was apparently invented), b) her nobility (the monogram of her father in the second “painted tondo”), c) her artistic talents (the Latin inscription states that she made the portrait) and, well, naturally – don’t you think? – for a would-be bride, d) the fact that she is a virgin (virgo, right-end of the circular inscription. – All of these elements in the painting say something about Anguissola, but also about what kind of man Anguissola is looking for, i.e. noble, Italian and appreciative of her artistic talents! (Literally, “prince charming”, one may say!) – There is no “gender issue” to study here, not in the 20th century sense anyway!

This or any other painting can be studied – and becomes interesting to study – only after you properly take into account all of these cultural and contextual elements. – Why did Sofonisba Anguissola chose a tondo shape for her self-portrait? – We know from the cultural context that the portrait and the self-portrait formed back then a relatively new genre related to the rise of a commercial and individualistic society; we also know that this genre had a distinct social function, it wasn’t a biblical or a secular grand “history” that decorated a cathedral, the salon of an aristocratic mansion, a hallway or a princely chamber in a palace : it served only to present, to introduce “somebody who was somebody”, as we say today (Henry VIII of England married some of his wifes only on account of Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait, for instance! even though that might not have been the best idea art served…) – so, the portrait presented somebody, it made an artistic and rethorical visual statement, for special occasion, regarding the person represented, and the self-portrait was an even more interesting kind of social and artistic statement of this kind, which involved self-reflection or self-examination on the part of the artist, beeing particularly sought after by the art collectors of the era, as a sort of final “signature” of an established painter set among the other paintings on the walls of their quadreria.

But there is one more contextual element that is important to really understand Anguissola’s tondo-self portrait – heraldics! Her tondo-self-portrait contains within it another “tondo” with the monogram of her father, who was presumably from the minor Lombard nobility. Well, in Florence back then, and in Italian and more generally continental heraldics ever since, the escutcheon of the Coat of Arms of a Lady is not shaped as a shield, but as a cartouche, that is an oval or a tondo! And this fact is essential in understaing this particular piece of painting.

Now I think we can sum-up what Anguissola’s tondo self-portrait means, as it were : it is a self-reflection, a mirror-painting, as any self-portrait, meant to display her aristic talents, but also – crucially and much more importantly! – this self-portrait is meant to display her Italian aristocratic pretentions to a viable suitor! – Think of this portrait as a sort of a matrimonial ad, in pop American terms, from a girl who really knew what and who she wanted (although obviously American pop-culture doesn’t help much to understand art!)In its social function, this is a very different type of self-portrait than the self-portrait of Lavinia Fontana, which is meant to showcase her as a professional cultivated painter. – Bottom line : without correctly interpretatig its historical context, its intertextual comments on the other arts (essential in this case is the comment on armorial art) and the artist’s intention, one can say whatever he or she thinks about a certain painting, armed with no matter what cool and fashionable “social theory”, but all this that nothing to do with art history at all in my opinion.

Hello Bogdan. Thank you taking the time to respond. I actually think that my understanding of “gender issues” actually relates to many of the things that you have discussed here. In my opinion, gender studies within art history involves the examination of any visual practice that relates to a particular gender. Paintings that relate to marriage (either in attracting a husband or in stressing the marital status of a woman) is part of this approach. I think your discussion about stressing the virginity of Anguissola aligns itself with my discussion of modesty and how Anguissola covered her figure.

I also think that historical context is crucial in understanding the intent for artists. Where there is an absence of art historical information, however, I do not see a problem with posing possible theories or musing on visual elements until further historical (i.e. textual) documentation presents itself. Personally, I do not have problem with people making modern associations with works of art, if it helps them to connect with a work of art and generate new ideas. I find such curiosity to be healthy. Regardless of theory or approach, a historian will never be able to fully place himself or herself in the historical context, language, and mindset of a historical era to which he or she does not belong. When I use feminist or postmodern terminology in posts such as these, I try to be very careful and noncommittal in my writing, to show that these are simply ideas which still require more research and historical documentation.

All this being said, I am not familiar with your interpretation Anguissola’s self-portrait as being “meant to display her Italian aristocratic intentions to a viable suitor.” Where did you find your information? Are you familiar with a primary text that discusses this particular portrait? I am familiar with another theory that this probably was painted in as a gift for a princely patron in Italy or Spain. In other words, the goal for this painting is thought to have been to secure employment at court (not a matrimonial ad). This theory makes sense to me, since the text in painting stresses that the painting was done by Anguissola’s own hand. But I do think that you have presented some good points about Anguissola emphasizing her status as a virgin, and I would be interested in finding more primary sources on that topic. As of yet, I have not found a primary source which actually explains the function for this painting.

In the self portrait at the clavichord, am I seeing a tear from her eye or what is that anyway? It’s very obvious. Thanks.

Hi James! Thanks for your comment! I can see what you are saying about how it looks like a tear coming from her eye. I wonder if the painting needs to be cleaned, and that discoloration is from dirt or debris? A 16th-century copy of this painting was sold by Christie’s a few years ago, and it doesn’t look like there is any type of mark under the eye to suggest a watery tear.