Wednesday, June 19th, 2013

The Slashing of Velasquez’s “The Rokeby Venus”

Velasquez, "The Toilet of Venus" (also called "The Rokeby Venus), 1648. The National Gallery of Art, London. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Last week I met a feminist scholar who mentioned that she likes to show her students Velasquez’s “The Toilet of Venus” (commonly known as “The Rokeby Venus”) when she takes students to London on a study abroad program. This scholar teaches her students about the suffragette Mary Richardson, who slashed this canvas multiple times in 1914 in order to protest the recent arrest of suffragette leader Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst.

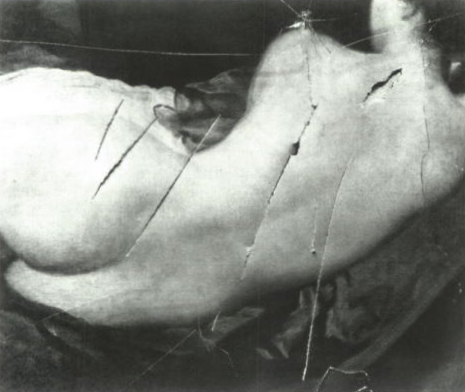

Detail of damage to "The Rokeby Venus." The attack by Mary Richardson occurred in the National Gallery 1914. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

I recently watched a BBC documentary (from “The Private Life of a Masterpiece” series) that covered more details about this attack (beginning about 32:17 in the linked video). At the time, Mary Richardson did not mention that she was bothered by the painting itself. However, Richardson mentioned in 1952 that she was bothered by the subject matter of this painting (as a female nude which attracted the attention of male viewers); this sentiment appropriately encouraged the soon-to-be feminist movement to uphold this attack a symbols of feminist attitudes toward the female nude.1

I think that the image of the slash marks are particularly interesting, because they remind the viewer that the Venus is actually an illusion which is painted on a two-dimensional surface. It’s also interesting to see how the media responded to this attack, since they cast Mary Richardson as a murderer (referring to her as “Slasher Mary,” which is a charged term given that Jack the Ripper killings took place a few decades before). Since Venus was proven to be an illusion instead of an actual body, Richardson had essentially “killed” the Venus.2

It is also interesting that Richardson concentrated her attack on the body of the Venus figure itself, as if to prevent the back and buttocks from serving as palpable, believable fetishes for the male viewer. In its original (now restored) state, this painting is well-construed for fetishization: the back and buttocks are highlighted as objects, especially since the “subjecthood” or “personhood” of the female is lessened through the obscured face (which is not only turned from the viewer, but is represented in the mirror in a very blurry, undefined manner). Richardson’s marks, however, challenge and defy this fetishization.

Do you know of any other physical attacks on works of art by feminists? Do you have any other thoughts on what new meanings were created by Richardson’s slash marks?

1 In 1952, in an interview, Mary Richardson said, “I didn’t like the way men visitors gaped at the painting all day long.” This quote is mentioned in “The Rokeby Venus” episode from “The Private Life of a Masterpiece” BBC series, but also found at “Political Vandalism: Art and Gender” found here: http://www.angryharry.com/rePoliticalVandalism.htm

2 Laura Nead discusses how the media used words that seemed to suggest that wounds were inflicted on an actual body, instead of a pictorial representation of a female. See Lynda Nead, “The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality”. (New York: Routledge, 1992), 2.

There were several other iconoclastic attacks by suffragettes, including one on Millais’s portrait of Thomas Carlyle (in the National Portrait Gallery). Why Carlyle? Was it his association with the “great man” view of history and Victorian notions of biography (and thus, by itself, portraiture itself)? Carlyle also appears on the exterior of the NPG, in sculpted form.

My favourite example, however, is the case of suffragette-defaced pennies. One of these featured in Neil MacGregor’s excellent “History of the World in 100 Objects.” See: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/iVUVhaKVREWjsHrr9IoOOA

Ben

Thanks for your comment, Ben! Your mention of Carlyle led me to Rowena Fowler’s article, “Why Did Suffragettes Attack Works of Art?” Fowler writes that the portrait of Carlyle “was slashed with a butcher’s cleaver by a ‘young woman of

refined appearance and very respectably dressed,’ who gave her name as “Annie Hunt”; Carlyle’s head was cut “through the left eye as far as the cheek’ (‘The Morning Post,” 18 July 1914)” (p. 122). If anyone is interested, you can locate the article here:

http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/journal_of_womens_history/v002/2.3.fowler.html

At the end of the article, Fowler lists all of the artworks attacked in 1914, beginning with the Rokeby Venus. I’ve included the list below, but anyone who is interested can find more detailed information of the attackers and locations for the art in the article’s appendix (p. 125).

– 10 March, Mary Richardson attacked Velasquez’s “Rokeby Venus”

– 4 May, Mary Wood attacked Sargeant’s “Henry James”

– 12 May, Gertrude Mary Ansell attacked Herkomer’s “The Duke of Wellington”

– 22 May, Grace Marcon attacked Bellini’s “The Agony of the Garden,” “The Madonna of the Pomegranate,” and “The Death of St. Peter, Martyr” attacked. Gentile’s “Portrait of a Mathematician” and a votive portrait from the School of Gentile also attacked.

– 22 May, Maud Kate Smith attacked George Clausen’s “Primavera”

– 23 May, Maud Edwards attacked Lavery’s “Portrait Study of the King for the Royal Family at Buckingham Palace, 1913” attacked

– 23 May, Nellie Hay and Annie Wheeler smashed a glass display case of a mummy at the British Museum (this is not a work of art, but a disruption that involves a museum space)

– 3 June, Ivy Bonn attacked Bartalozzi’s “Love Wounded” and Shapland’s “The Grand Canal, Venice” with a hatchet at the Doré Gallery

– 9 June, Bertha Ryland Romney’s “Master John Bensley Thornhill” attacked (note that date is incorrect in the article but corrected here)

– 17 July, Anne Hunt attacked Millais’s portrait of “Carlyle”

Fowler writes that cartoonists had a heyday with all of the damage caused by suffragettes. A particular favorite of mine is Donald McGill’s portrait of a couple gazing at the Venus de Milo, with the man commenting, “Now aint that a shame, I bet it’s them suffragettes done it!!” See image here:

http://books.google.com/books?id=nAtYtZ6uN1EC&lpg=PA31&ots=OBMsGEQkZ8&dq=Now%20aint%20that%20a%20shame%2C%20I%20bet%20it's%20them%20suffragettes%20done%20it%22&pg=PA31#v=onepage&q&f=false

UPDATE 7/15/22: I have created a slideshow with images of the attacked works of art and photographs that I could find of the damage.

Very interesting! However, does the list provided by Fowler of artworks attacked by suffragettes undermine what may be interpretations unduly influenced by post-war theories and practice of women’s liberation? For instance, your own interpretation of the slashing of the Rokeby Venus in terms of its female nudity seems less convincing in light of the other attacks, none of which seem to be on a painting of nudes. Of course the Rokeby Venus and other traditional nudes such as Titian’s indeed involve presenting female nudity to the gaze of salacious males — in other words, sex — but it seems to me harder to see this as a significant part of the suffragettes’ slashing.

Hi Andrew! You have brought up an interesting point and I have considered a similar point of view. Mary Richardson was not vocal about being bothered by the nudity of the Velasquez painting until almost forty years after she attacked it, and I think it is curious and telling that later feminists have latched onto her later statement. It seems like Richardon’s added motivation to attack this particular painting, beyond the protest of Mrs. Pankhurst’s arrest, was rather personal (and perhaps was kept from the other suffragettes?).

Nonetheless, I do think that the concentrated slash marks on the figure’s body visually defy and challenge Velasquez’s figure from becoming a fetish. Whether Richardson intended to challenge this fetishization in the way that I have described is unknown, but the I think that my personal reaction is justified from solely a visual perspective.

Thank you for your perceptive comment!