Saturday, March 23rd, 2013

Christian and Islamic Art: Flesh vs. Word

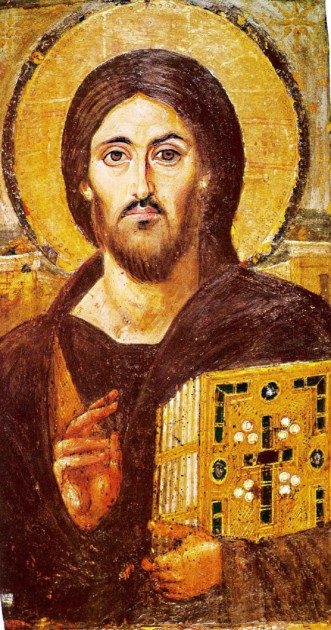

I just finished a very busy, busy quarter. One of the classroom discussions that I will remember most involved a comparison between Islamic imagery and Christian imagery. Before discussing Islamic imagery, I introduced my students to Byzantine icons. We discussed how the frontal orientation of figures and direct eye contact were essential in the icon tradition, since such compositional devices encourage interaction with the viewer.1 In the case of the icon of Christ from the Monastery of Saint Catherine (one of the few icons which escaped destruction during the period of iconoclasm in the 8th and 9th centuries), we also discussed how the composition of Christ’s face was significant: “The right side of Christ’s face (our left) is open, receptive and welcoming, whereas his left side – Byzantium’s tradition side of judgment and condemnation – is harsh and threatening, the eyebrow arched, the cheekbone accentuated by shadow, and the mouth drawn down as if in a sneer.”2

To continue this discussion, I emphasized to my students that in many ways figural imagery lends itself to Christianity: Christ assumed a human body (“the Word became flesh”) and Christians are supposed to emulate the actions of Christ. Christians are also encouraged to emulate the lives of virtuous individuals, such as saints and martyrs. Such emulation and mimicry is encouraged when there is figural imagery, perhaps especially when such imagery exists in a narrative scene.

To emphasize this point about mimetic behavior, I had my students read a short article by Gary Vikan on Byzantine icons: “Sacred Image, Sacred Power.” I really like Vikan’s discussion of images and imitative behavior, which he supports with a 4th century quote from St. Basil. Basil explains how there is a parallel between the workshop practice of artists and the appropriate behavior of Christians:

“…just as painters in working from models constantly gaze at their exemplar and thus strive to transfer the expression of the original to their artistry, so too he who is anxious to make himself perfect in all the kinds of virtue must gaze upon the lives of saints as upon statues, so to speak, that move and act, and must make their excellence his own by imitation.”3

Although there were periods of iconoclasm in Christian history, I believe that the mimetic behavior of Christians is one of the reasons that figural imagery generally has prevailed in Christian art. And even during some of the comparatively later periods of iconoclasm, such as that experienced by Protestants, the secular imagery at the time was still based on mimetic behavior – particularly the moralizing themes found in Northern Renaissance and Northern Baroque art. Even when Christians weren’t looking toward strictly religious subject matter, they still looked toward paintings to help enforce what behavior they should mimic or avoid. Such moralizing paintings were created by Jan Steen, including The Dissolute Household (ca. 1663-64, see above).

In contrast with Christianity, Islam doesn’t have exactly the same type of foundation in mimetic behavior: God revealed himself to Mohammad through his word, and therefore the words of the Qu’ran take precedence in religious imagery.4 For Islam, words are the embodiment of God. This point was emphasized in an article that I shared with my students, “The Image of the Word” by Erica Cruikshank Dodd. She explains, “The written or the recited Koran is thus identical in being and in reality with the uncreated and eternal word of God. . . If God did not reveal Himself or His Image to the Prophet, he nevertheless revealed a faithful ‘picture’ of his word.”5 God sent down his image in the form of a book. In turn, Muslims decorate the interior and/or exterior of their religious spaces with phrases from the Qu’ran, as can be seen on the exterior of the Dome of the Rock (a structure that Oleg Grabar describes as a “very talkative building”).

Despite the fundamental differences in Islamic art and Christian art, it is fun to notice some visual similarities. I like to consider how the words of the Qu’ran, as depicted in flat, two-dimensional text, have parallels with the flat stylizations found in many Byzantine icons. In some cases, as seen in the kufic script above, the elongation of the script has an interesting parallel with the elongation of human figures in Byzantine art. Furthermore, both text and image limit the distance between the viewer and representation by rejecting three-dimensional illusionism. As a result, the devout viewer is able to get as close to the embodiment of God as possible, whether that be an image or text.

1 Other visual devices in icons which encourage interaction with the viewer include the gold background (which removes the distraction of earthly or “real” time), half-length figures (to push the figure closer to the viewer), and overly-large eyes.

2 Gary Vikan, “Sacred Image, Sacred Power,” in Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World by Eva R. Hoffman, ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 137.

3 Ibid., 140.

4 Although Muslims strive to maintain lifestyle outlined and practiced by the Prophet Muhammad, as explained in the Sunnah, the writings of the Qu’ran are the primary source for the Islamic faith and its religious art.

5 Erica Cruikshank Dodd, “The Image of the Word,” in Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World by Eva R. Hoffman, ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), 193.

Yours is a beautiful, inspiring blog which I would love to follow. I’ve bookmarked the page, and I will subscribe, if I can find the way. Thank you for sharing your window.

Another point is connection is in Christian manuscript illuminations–Hibernian and Anglo-Saxon manuscripts especially, like the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels (not so incidentally?, some argue that the carpet pages from these manuscripts are inspired by Islamic prayer carpets). Devotion to the Holy Name also was quite popular in the later Middle Ages, so in manuscripts like British Library Additional 37049 you have multiple instances of Christ’s or Mary’s name functioning rather like an emblem–they’re clearly meant to be a focus of devotion. That manuscript also has pretty extraordinary combination of the figurative and the verbal in The Charter of Christ, in which Christ’s crucified body is also the scroll of the charter between him and mankind. The words are written in his blood, and the seal is his heart. Not quite the same, but interesting.

(That’s just apart from your regular old extraordinarily elaborate initials–the foundational aesthetic justification for which is Christ being the Word, etc.)

Medieval Hebrew manuscripts have a similar approach to Islamic when it comes to the word, like in this one:

http://www.hebrewtypography.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/BL2.jpg

The last paragraph was especially interesting! I am currently taking an Islamic art class, and we frequently talk about the visual relationship between Islam and other cultures, including the cultures which surrounded the geographical location in which Islam was born as well as its influences on Western art.

The image of the Word is truly an identifying feature of the Islam. When looking at coins dating from the early seventh century during the first few years of the Umayyad caliphate, one sees direct appropriation of imagery from Sassanian and Byzantine cultures. However, after moving to Damascus where a large Christian population lived, caliph Abd al-Malik realized that if Islam was going to make a statement, they needed something unique. He altered the imagery on the coins, featuring the Kufic script and verses from the Quran. And from then on Islamic religious imagery was an-iconic and writing became an essential aspect of Islamic culture. This rich calligraphic tradition was the highest form of art in the Islamic world, an act of creation akin to God’s creation. In Islamic belief, God is a scribe, and his first invention was the pen. Hence there was no need for figural representations; the words themselves were the images. What a simple and beautiful approach to religious representation.

Question for Zillah: When looking at Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, I have wondered what sort of contact England had with the East at that time in history. Are you aware of any trade that took place between these two groups of people or any scholars who have written specifically on this? I would love to learn more.

Thanks for writing!

Emaline,

I’m not an Anglo-Saxonist so I can’t tell you anything definite, but I know Michelle Brown works on Insular/eastern artistic and cultural influences. Looking at her CV, she apparently has an piece coming out that addresses it, and her 2009 ‘From Jerusalem t Jarrow’ should as well. It looks like both those pieces discuss Eastern Christianity specifically, but I’ve heard her posit the connection with Islam in lectures, so I’d wager she addresses it in the articles too.

http://research.sas.ac.uk/search/staff/145

This post is just… I’m so excited about it that I have goosebumps. It’s perfect. I have taken more Islamic art classes than any other field, and I think this post really captures the essence of it – especially the paragraph about the word, and decorating with the word. For a graduate seminar this semester, I’m writing about the Dome of the Rock and its relationship to the Aachen chapel built by Charlemagne, and I have been stagnant on the topic for about a month, but leave it to AW to inspire me back into being able to talk about the relationship again 🙂 Thank you!

Monica,

What a refreshing post! I have been searching for these connections for such a long time.

There is one thing we have to keep in mind when comparing Christian and Islamic works of art – it is not just the juxtaposition of imagery as opposed to words but as you mention above according to the Bible Christ assumed a human body “the Word became flesh” but it is not possible to and forbidden to reify God according to the Quran which is proposed to be verbal expressions similar to Bedouin poetic imagery.

But we do have something in Ottoman art, Hilye-i Serif, which is a description/representation of the Prophet Muhammad, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hilya. Possessing and reading the Hilye is supposed to be protective so people hang it in their homes. Also, in Islamic iconography the rose is the prophet while the Tulip is the representation of God.

Emaline, Thanks for your comment about God being a scribe, and his first invention being the pen. That is lovely.

The success of Islam is cited as one of the propelling forces behind iconoclasm, you know. Just think if it wasn’t for Theodora, what would we be discussing today.

Thank you so much Monica for posting about this and the lively conversation that is taking place on your blog.

Hi Victoria! Thank you for your kind comment. I have a subscribe link at the top of my blog home page (on the right side of the screen). If you use an RSS feed to follow blogs and/or blog comments, you may find those links helpful.

Hi Zillah! Thanks for your comment and response to Emmaline. I also think that the East and Anglo-Saxon is interesting.

Also, I’m glad that you mentioned the Book of Kells. One of my students did a research presentation on the Book of Kells this past quarter, not long after we had this discussion on Christian and Islamic imagery. She mentioned some of the visual connections between the interlace forms, calligraphy, and Islamic imagery. And, given the context of this post, it’s interesting that the most famous page of the Book of Kells, the “Chi Rho Iota” page, refers to the incarnation (the “Word made flesh”):

http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/book_of_kells.html

I’m intrigued that there are instances in which Christ’s or Mary’s name were seen as emblems and objects of devotion, especially since they stand apart from the elaborate initials tradition. I wonder if there could be any Eastern influences (either Islamic or even Jewish) that are influencing this type of tradition in late medieval art, perhaps as a result of the Crusades? It would be interesting to see if there is any Crusader art which has this focus on the Holy Name. I can’t think of any off the top of my head, though.

Hi Emaline! Thanks for your comment. I don’t know very much about the imagery on coins made by Islamic cultures, so I really appreciated your connection. It’s interesting to consider how coins were used from a Western perspective, though, especially in the Crusader states (when Eastern and Western artistic traditions combined together). At that time in the Holy Land, Crusaders struck coins with Arabic inscriptions that were later combined with the symbol of the cross. So even though Christians adopted the practice of coins with Arabic inscriptions, they still felt compelled to include representational imagery (a cross) too. My students and I read about this practice in Crusader art during this past quarter, in a chapter on Crusader art from this new book:

http://www.amazon.com/Art-Visual-Culture-1100-1600-Renaissance/dp/1849760934

Also, your discussion of how God is considered to be a scribe is a great connection to my post! Thanks!

Hi Amy! Thanks for your comment. I’ve pulled you out of your lurker status, I see! 🙂

I think that your connection between the Dome of the Rock and the Aachen chapel is really great. Good luck with your seminar paper research. I’ve also read about connections between the Aachen chapel and San Vitale in Ravenna. I wonder if Charlemagne (or Odo of Metz) could have become familiar with the Dome of the Rock (perhaps the floor plan?) by way of Ravenna?

I love that you have taken more Islamic art classes than any other. Perhaps you’ll be able to find some connections between Islamic art and Caravaggio one day.

Hi Sedef! Thanks for your lovely comment! I’m especially intrigued about this connection between tulips and God, especially since the tulips in my yard started to bloom this morning! If you know of any sources that discuss this imagery (or the rose imagery with the Prophet) more, I’d love to know of them. I noticed the depiction of the rose at the end of the Hilye article that you mentioned, which was neat. I did do a little bit of research on my own too, and found a bit of information on this article about a Tulip Museum in Istanbul:

http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/everything-about-tulips-in-a-museum.aspx?pageID=238&nid=43382

Speaking of Islamic imagery, I remember seeing some depictions from an Islamic art class in which the Prophet Mohammad was depicted with a veil across his face. One such Ottoman manuscript is found about near the top of this webpage:

http://facesofmohammed.ip0.eu/

By the way, have you seen this “Face of Mohammed” website? You may find it interesting from an East-West perspective. Thanks for your comment!

To further this discussion of Christian and Islamic imagery, Hasan from “Three Pipe Problem” has written a post about the imagery of the egg. This is another fascinating connection. Please check it out!

http://www.3pipe.net/2013/03/piero-della-francescas-symbolic-egg.html

Monica Hi again,

Ever since this post I have been doing more research on representation in Islamic art – I am still working on finding you sources. But in the meantime I did find a facinating paper by David J. Roxburgh “Concepts of the Portrait in the Islamic Lands” (when you google this the pdf comes up- the link is too long to clutter up your page)

And another fascinating bit of information I came across recently is in regards to Islamic coins during the Caliphate of ‘Abd al-Malik’ while the caliph used the standard iconography of the Byzantine emperors with slight variations like getting rid of the cross, there was a gradual transition to his own iconography before the coins with Arabic inscriptions. At one point he had coins struck with the image of ‘Standing Caliph’ but the coins struck in Jerusalem had a figure that was different than the figure of the caliph in the series – which according to the Met exhibition catalog of Byzantium and Islam bared the inscription “Muhammad the messenger of God” raising the question “Could this be the image of the Prophet himself?”

Standing Caliph

Hi Sedef! This is very interesting information, especially the idea that the “standing caliph” might actually be a representation of the Prophet. It is curious that this figure and coin (struck in Jerusalem) is different from the those struck in Damascus. The third image embedded in this BBC site has an example of another coin issued under Caliph Abd al-Malik’s reign for comparison, if anyone is interested. This figure does look quite different from the figure on the Met’s coin:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/YQMPZkAXRW6iYDCe5L4KSA

Thanks for your comment and the link to the Met page!

Making judgments of value requires a basis for criticism. At the simplest level, a way to determine whether the impact of the object on the senses meets the criteria to be considered art is whether it is perceived to be attractive or repulsive. Though perception is always colored by experience, and is necessarily subjective, it is commonly understood that what is not somehow aesthetically satisfying cannot be art. However, “good” art is not always or even regularly aesthetically appealing to a majority of viewers. In other words, an artist’s prime motivation need not be the pursuit of the aesthetic. Also, art often depicts terrible images made for social, moral, or thought-provoking reasons. For example, Francisco Goya ‘s painting depicting the Spanish shootings of 3rd of May 1808 is a graphic depiction of a firing squad executing several pleading civilians. Yet at the same time, the horrific imagery demonstrates Goya’s keen artistic ability in composition and execution and produces fitting social and political outrage. Thus, the debate continues as to what mode of aesthetic satisfaction, if any, is required to define ‘art’.

Hi Christina. Thanks for your comment about aesthetics, value, and satisfaction. I think there are a lot of ways by which one (either the artist or the viewer) can determine “value” in art. The artist and the viewer may even disagree on what aspects of the work of art have value, too. Along these lines, viewers from a different culture than that of the artist will likely have a different interpretation of value and meaning.