Wednesday, May 16th, 2012

Justinian Mosaic Altered Not Once, but Twice!

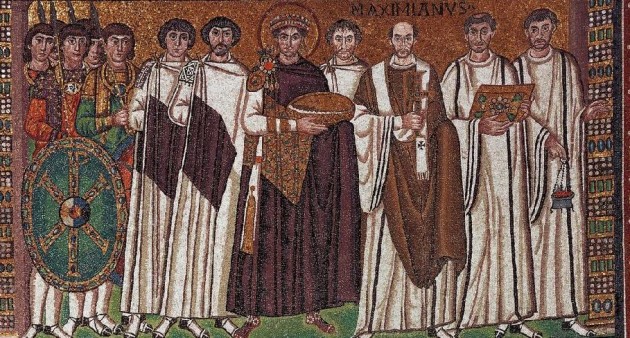

Detail of Justinian and His Attendants, wall of the apse of the San Vitale Church (Ravenna), c. 545-546. Church consecrated 547. Some alterations date c. 1100.

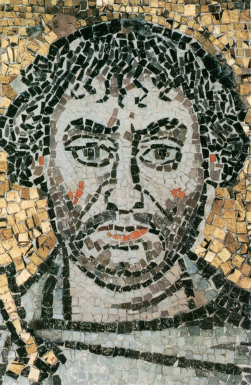

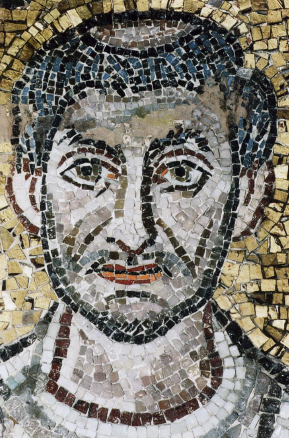

The mosaic “Justinian and His Attendants” at San Vitale (c. 544-545 CE) is one of the most famous works of art from the Byzantine period. It also happens to be one of my favorite piece from this era. It is commonly known that there were some alterations made to this mosaic just a few years after it was created, probably between 546 and 548. We know that the head of the archbishop (who is standing to the left of Justinian or the right side from the viewer’s perspective) was altered and the inscription Maximianus was included at this time. This change probably is because Bishop Victor was originally depicted in the mosaic. After Victor died in 545, Maximian came into power and wanted to have himself depicted instead. It is thought that Maximian needed to include his portrait as an assertion of power, since his authority was insecure at the time. In fact, around the time of this alteration the archbishop had recently been banned from entering the city of Ravenna, due to a dispute with its citizens.1

Another one of the early modifications was the inclusion of a courtier who stands in between Justinian and the bishop (see above). If you look closely at the overall composition, you’ll see that this individual does not have any feet (which can be explained with the understanding that this figure is a late addition). It is thought that this figure represents John the Nephew of Vitalian, who was second in command to the commander-in-chief of Italy (the latter is thought to be depicted on the right side of Justinian, wearing a beard). Maximian may have seen potential in John the Nephew’s power, and therefore decided to include him in the composition.2 Although it does seem like it would be humiliating to be included in the background of the composition, John the Nephew did get a prime location between the emperor and archbishop.

However, in addition to these early alterations there are some other alterations to this mosaic which seem to have taken place several hundred years later, probably around 1100 CE. Isn’t that interesting? In the 1990s, scholars Irina Andreescu-Treadgold and Warren Treadgold published results on some technical analyses of the Justinian mosaic. The publications revealed changes in the scale and materials of the tesserae that were used.3 Based on these studies, I wanted to present some of the medieval restorations that took place.

One of the interesting additions in the c. 1100 restoration is the tonsure (shaved top of scalp) which was added to one of the deacons on the right side of the mosaic. Although the origins of the tonsure are unclear, I am not familiar with any examples of the tonsure that exist before the 7th and 8th centuries. (If anyone does know of examples, I’d be interested to learn about them!) It’s important to realize that the tonsure might not have existed in the sixth century, when this mosaic was originally made!

Other medieval alterations include the emperor’s crown, which apparently was simplified and diminished in scale (although it is interesting to note that Empress Theodora’s crown, depicted in another mosaic in the San Vitale apse, is an original). A fibula (or brooch) was also added to Justinian’s attire in this later alteration (see above). I think that this inclusion of the fibula is rather interesting – perhaps the mosaicists wanted to visually compensate for the fact that they gave Justinian a smaller crown? Finally, the smaller pieces of tesserae at the beginning and end of the Maximianus inscription indicates that there was an alteration in this place, too.

Isn’t it interesting that we can deduce through formal and technical analysis that this mosaic was altered several hundred years after its creation? The nuanced history of this mosaic makes me love it all the more. What do you like best about this work of art?

1 Irina Andreescu-Treadgold and Warren Treadgold, “Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale,” The Art Bulletin 79, no. 4 (1997): 721. Maximian had been barred from Ravenna because he had supported Justininan’s Edict of the Three Chapters. The inclusion of himself with the emperor in this mosaic serves to visually reinforce Maximian’s support of the emperor.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid. See also Treadgold, “The mosaic workshop at San Vitale” in A. M. Ianucci ed., Mosaici a San Vitale e altri restaur. Il restauro in situ di mosaici parietali, Ravenna, 1992, pp. 31-41. The restoration is also briefly discussed in Sarah E. Bassett, “Style and Meaning in the Imperial Panels at San Vitale,” Arbitus et Historiae 29, no. 57 (2008): 56.

Thanks for this wonderful post M. I was just watching Bettany Hughes’s new series “Divine Women” which covers Empress Theodora in some detail and mentioned this mosaic depiction of her.

I’m interested in the terminology used – “formal” vs technical analysis – is this the term used in art history texts to denote looking at compositional or iconographic details – or is it used to record observable indications of technique used and additions. In the literature I’ve been working from on paintings, conservation type reports mostly describe “visible light” analysis with reference to other modalities which examine objects in other bands of the visual spectrum (infrared etc). They do make commentary on changes – such as seen in the Prado Mona Lisa report, but it is still is not called “formal” – I am curious to know how this term is being used here – and whether it is mentioned in the sources you used or is a clarification you have included.

many kind regards

H

Hi H! Thanks for your comment. Now that you mention it, I used the word “formal” for clarification (I suppose because I am an art historian and that term is most common in my area of the discipline). In using the word “formal,” I am referring to visual analysis of the physical form of the mosaic (being completely apart from iconographic analysis). In this case, I had in mind the physical scale of the tesserae (something that can be observed with the naked eye). To me, the more in-depth analysis of mosaic phases, dating and perhaps even medium (beyond what can readily be perceived by the eye) constitutes the more “technical” aspect of the study. In the articles which I read, however, the description “technical study” was used.

You have brought up an interesting point: there must be overlap between the usage of “formal” and technical, depending on who is writing the article/commentary. It is interesting to know that conservation reports use the term “visual light” analysis. I am going to be more aware of these similarities (and also distinctions!) of these various terms in my future research and writing.

Strangely, late this afternoon while sitting at my desk at work, I thought of this mosaic and its companion in San Vitale. I have always liked them both, so I’m so glad you wrote about the Justinian mosaic and have brought it to my mind again!

I think what I like is the asymmetry and the similarities of the two mosaics – they’re the same, but different. And although the faces all look similar, they still have individual characters. The compositions look so stiff, but also have a sense of capturing a moment, both a moment in the day and a moment in history.

That’s not a very formal way to look at it, but it’s the stories more than the analysis that I love about art!

Hi Val! I’m glad that we were on the same brainwave yesterday. I also love how these two pieces are both similar and different. Theodora’s mosaic, to me, seems a lot more elaborate than Justinian’s piece – partly because of the architectural setting, but also because of the variety in clothing and poses. Just this evening I was struck with the difference between Justinian and Theodora’s robes; Theodora’s robe is decorated with a depiction of the Three Magi, but Justinian’s robe is plain. It is the extra details in Theodora’s mosaic that especially give the sense that these panels “capture a moment.”

Thank you for this informations!!!

so fascinating, M!! i remember being very excited to see this and when we got there, it did not disappoint. the colors were so vivid, something that you cannot see through pictures or slides!

I find it so interesting that the court went to such lengths to make their stories fit into the history of the reign. The mosaic artists must have cringed at the challenges of removing and replacing tesserae, and then making them all mesh. I wonder if there were any obsessive compulsives in the patrons of the cathedral that lost track of their worship over the oddities. The mosaics are beautiful and wonderful to study no matter what.

Thank you for the comments, everyone! Julie, I also think that the mosaic artists probably didn’t enjoy the challenge of modifying mosaics – what a lot of work! If only we knew about more personal reactions to the mosaic modifications, from both the artists and the patrons of the church. Wouldn’t that be interesting (and perhaps amusing) to know?