Thursday, April 26th, 2012

Watercolor as Underdog

One of the classes I’m teaching this quarter includes a lot of avant-garde art from the 19th and 20th centuries. Last week, a student observed that we haven’t been discussing watercolor paintings as a class. I thought this was a good observation, and responded that avant-garde painters often (but definitely not always) stick with oil and canvas as a medium. This reliance or insistence on oil makes sense for a lot of reasons. On one hand, avant-garde artists seemed to want to “reference” the tradition of oil painting while simultaneously establishing their “difference” from that tradition (to borrow two phrases from Griselda Pollock).

This comment about watercolor, though, has got me thinking. On a whole, I would say that watercolors are not highlighted or discussed very much in general art history textbooks (or in the artistic world at large). In some ways, I think this is a little surprising. Water-based paint has existed since prehistoric and ancient times. Several significant European painters also were interested in watercolor, like Albrecht Dürer (see above).

However, it seems to me that watercolor often has played second fiddle to other mediums, including oil paint. (Maybe it’s part of our human psyche to be reliant on all types of oil – hence the contemporary issues with oil drilling today! Ha!) In fact, in 1804 a group of disgruntled watercolorists banded together in Britain. These artists were upset that watercolor did not receive very high status by the Royal Academy (which had created a hierarchy of artistic mediums). One British watercolorist, William Marshall Craig, even felt compelled to debate the superiority of watercolor over oil painting.1

So, is watercolor really less pervasive of a medium than other types of paint (from a historical standpoint), or does our current view of history simply privilege other mediums? Do we not value watercolor as a medium very much? I haven’t come up with all of the answers (feel free to leave your own opinion), but here are some of the things that I’ve thought about:

- Going back to the Baroque period, watercolor was used by artists for preliminary compositions, cartoons, or copies. (One such example is a kitchen scene by Jacob Jordaens, which happens to fit quite nicely with my recent post on meat and art). Perhaps watercolor has escaped a lot of attention because it is seen in connection with “unfinished” or “lesser” works of art.

- Today art museums do not highlight watercolor as much, due to the fragile, light-sensitive nature of the medium. I remember a curator once telling me that watercolor paintings can only be displayed for a short period of time (six weeks?) before they needed to be taken down or rotated with another painting. Perhaps if watercolor paintings were inherently a little heartier, then they would receive more exposure (ha ha!) to the public eye?

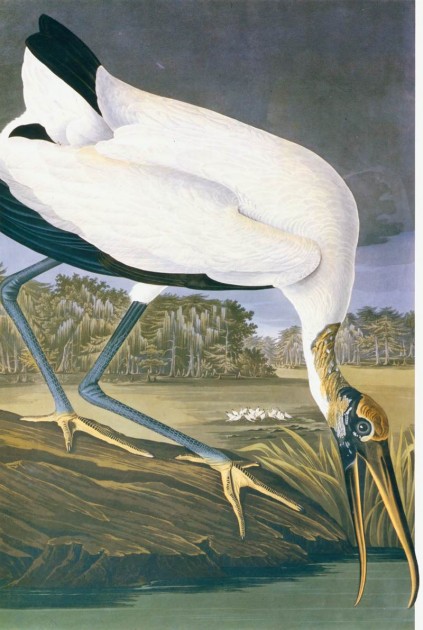

- Watercolor is also associated with things that are not strictly labeled as “fine art” (or, along these lines, “art for art’s sake”). For example, watercolor paintings often appear in naturalist field guides. The connection with watercolor and nature has been longstanding, perhaps reaching its zenith in the work of John James Audubon in the 19th century (see above).2

- Avant-garde artists might have wanted to “reference” the longstanding tradition of oil painting (and perhaps better challenge the Academy by using a medium which was valued at the time?).

I’d love to hear other people’s thoughts on the topic. Do we need to write some revisionist history to include more watercolor painting? What watercolor paintings do you enjoy and/or feel like they deserve more attention? Are there watercolor paintings that you find to be historically significant?

1 William Marshall Craig put forth four arguments in defense of the superiority of watercolor paint. First, he finds that watercolor gets a brighter range of tones than oil paint (partially because the white of the paper produces a brightness that is unattainable in oil). Second, he argues that transparent watercolors allow for clarity and detail that cannot be achieved with oil. (I personally don’t completely agree with that point.) Third, watercolors do not change in appearance when they dry, which is different from oil. Fourth, he finds that watercolor is better for working outdoors, which is necessary with the increasing interest in naturalism. I think this last point is really interesting, especially since he made these arguments several decades before Impressionism. If painters had focused on watercolors a bit more, I wonder if Impressionism (or a similar movement to Impressionism) could have happened several decades earlier. Craig’s arguments are outlined in the book, Great British Watercolors from the Paul Mellon Collection (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 2. Citation available online HERE.

2 Audubon is best known for his “The Birds of America” publication (1827-1838). The complete watercolor work of Audubon can be seen HERE.

I loved this post and i found it very intersting. I think that it would be very intersting to try to write a revisionist history to include more watercolor painting – maybe we would be surprised. I love watercolor paintings of many artists – Dürer and Turner, for example. And I agree with your opinions about the reasons why watercolour paintings (along with drawings and other media) are less valued than oil paintings. If I have the opportunity, I’m going to think about this subject on my future investigations.

We didn’t talk about watercolor paintings in my art history classes specifically, but we did discuss them quite a bit in my drawing classes. There’s a Watercolor Society of America that probably has some good resources on the history of watercolor.

Hi,

We had an exhibition abotu watercolour at the Tate Britain recently.

http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/watercolour

Based on my notes, here is what I can add to the subject:

In the beginning watercolour was used mainly for landscapes, miniatures and manuscripts to express precision of detail. This partially supports the claims of William Marshall Craig. If we think about manuscripts, we really cannot say watercolour has been a secondary art medium in the history of art(and we have just had a superb exhibition of manuscripts at the British Library: http://www.bl.uk/royal – these objects have also often fallen into oblivion due to their fragile nature so I guess you are right that watercolour doesn’t enjoy such a high status simply because they must stay hidden in dark rooms)

The use of watercolour flourished with the Enlightenment for depicting the flora and fauna as apparently it was really good for depicting things accurately. Its use also spread quickly thanks to its portability – with the increased number of travellers more and more people had to rely on it. So – at least in Britain – watercolour seemed to be very popular. I remember yet another exhibition in which the discoveries made in the New World were all depicted in this form of art medium.

http://www.britishmuseum.org/the_museum/london_exhibition_archive/archive_a_new_world.aspx

Yet Watercolour only earned its own place as an equally respected medium at the end of 18th century thanks to its easy portability during travelling; was also useful for doing sketches and working quickly outside; it earned a similar status to oil paintings and many societies were established upon it.

It mainly continued to be used in the genre of war painting – yet again thanks to its portability, but died out quickly after the Great War with the emergence of photography. I think there are many war paintings from the First World War executed in this medium.

My guess is that its faith comes down to its two main qualities, namely portability and fragile nature and these two forces seem to work in opposite direction.

Great post! I love your blog! I’ve wondered about this myself. I definitely think that the light-exposure/preservation problem with watercolor is an interesting point — maybe the lighter types of paper that are used for watercolor (and are literally left water-damaged in the process) seem “weak” and somehow “lesser” in comparison to the thick stretched canvases and wooden frames of oil paintings.

I also wonder if watercolor has historically (thinking in terms of the academic hierarchy you referenced) been deemed more “feminine/passive/ephemeral” with its softer edges, lighter coloring, and delicacy of medium, as opposed to the more “masculine/virile/eternal” bold brushstrokes, saturated color, and opaque solidity of oil paint. Much like the Impressionists with their erratic and unfinished (even “watery”??) brushwork and use of bright color were first thought of as effeminate (as Norma Broude points out in “The Gendering of Impressionism”).

I personally love watercolor. It takes a lot of skill to do it successfully — to control the flow of the paint, how much you load your brush, and how you layer your colors, which will bleed into each other.

I wonder how much watercolor was used for studies of paintings, as opposed to the finished product, usually done in oil. Maybe chronologically watercolor came first but was a thought of as a stepping stone rather the end in itself, like photography was viewed first only as a tool for better painting rather than an art form in its own right.

Anyway, I really like your thoughts on this, I think it’s an important and overlooked issue in art history!

Thanks for the comments, everyone!

@heidenkind, I’m going to look and see if the Watercolor Society of America has any information on the history of watercolor. Thanks for the tip!

@Charmagne: Thanks for your comment! (It’s nice to hear from you!) Your discussion of gender and watercolor is really thought-provoking. I wonder if you could even make some associations with the female gender and water, since women have historically been connected with water. (Off the top of my head, I’m thinking of fertility goddesses and Egyptian goddesses like Nut, the Sky Goddess. I wonder if one could argue that these associations continue into later history, too.)

I also wanted to include some messages that were sent directly to me in relation to this post. My friend Phin mentioned that watercolors are more easily damaged than other types of mediums (which ties into what I wrote about museums and light-sensitive watercolors). Phin says that watercolors can get damaged more easily by water, whereas oil paintings can sometimes be saved with water damage. Phin also thinks that watercolor might be coming back with artists like Shirley Trevena.

My friend Brad also mentioned that he thinks that it is hard to create color values with watercolor, because no ground painting or underpainting is used in watercolor. And because the medium is transparent, artists only have one shot to make things look right.

Brad also implied that watercolor predicates “a race against the clock,” since the artists needs to paint before everything dries. (My favorite quote from Brad’s correspondence was that “good watercolor is like controlled chaos.”) I think that this “race” requires more technique and precision on the part of the artist than other paint mediums, which could cause some artists to shy away from using watercolor. Oil paintings can be reworked (since the mediums dries slowly), but it is hard to rework watercolor. Due to this technicality, though, it seems like the medium should be given more status when ranked among other types of artistic mediums!

Granted she uses gouache instead of watercolor it is not oil or acrylic, Laylah Ali is a fantastic artist who uses this paint to achieve a very flat (texturally) (and I guess dimensionally too) image. Most of her paintings look printed, this is because of the gauche paint which is opaque and not transparent like watercolor.

She doesn’t use the wet on wet style of watercolor but she has a control using wet on dry with her brush that takes her months to finish a piece because of all the drying time and to achieve such even coats of paint.

I believe that, to some extent, the notion of any primacy of oils over watercolors, is a mere matter of momentum. Many people believe that oils are (rather vaguely and mistakenly) ‘superior’ and pass that belief onto their students, customers and other children. Belief begets belief.

I recall once a conversation with a gallery operator interrupted by a cold-calling, want-to-be artist. The discussion, overheard by me, became, albeit one-sided, rather heated. Eventually, the gallery operator returned and, in embarrassment, explained. The ‘artist’ had backed her demands with shrieks of, “But they’re genuine oils!!” She might have added, “Genuine canvasses!” I believe that today, this genre is shifting to a heated, “Genuine acrylics!”

Although watercolors indeed have suffered a plethora of permanence problems, so have oils. Cracking wooden panels. Lead pigments blackening others with chemical interactions. Deliberate errors such as Frankenthal’s ‘color fields’ with acidic oils applied to ‘stain’ a canvas without a protecting intervention of gesso. Etc. The list for oils is also endless.

The fact that museum’s can’t display watercolors without damaging them may be the most compelling reason whey watercolors are considered “lesser”–if people don’t see a particular medium when they visit museums, then the assumption is that it doesn’t live up to the curator’s notion of fine art. In fact, there are lots of museum curators who would love to exhibit watercolors, and museums that have amazing watercolor collections.

Thanks for the comments, Kelsey, Peter and Karen. I wasn’t familiar with the work of Laylah Ali before, Kelsey. Thanks for introducing me to her! I saw that she was highlighted on ART21. I look forward to watching the video and learning more about her. (I have to admit, though, that when I read your comment about the time-intensive process, I immediately thought of Jan van Eyck and the slow layering of oil paint. There’s that oil paint bias again!)

Peter, you have raised some good points about the problems inherent to oils. Perhaps we’ll see a shift in the future toward watercolor – as long as there are enough watercolorists around to start the trend (and beget more interest!).

Karen, I also think that the lack of watercolors in museums is a compelling argument. I wonder if watercolors were displayed more frequently, then we could foster or “beget the belief” (like Peter mentioned above) that watercolor is a noble and important artistic medium.

Zsuzi: Thanks for your comment! It went into a comment “spam” folder for some reason, and I just saw it now. I’m so glad to know that the Tate Britain recently had a show on watercolor! It looks like it was really great.

Thanks for all of the information that you added on this topic. That’s interesting to know that watercolor was used in war paintings, because of its portability. War paintings seem to weighty in terms of their subject matter; it’s interesting to think about how a fragile (yet portable) medium was used to compose these types of subjects. As you have mentioned, it seems like the fragility and portability of this medium seem to work in opposite directions.

Thanks for the tweet update – it was good to revisit this post and see the comments.

The National Galleries in Edinburgh and Dublin both have wonderful collections of Turner watercolours. These are the Vaughan bequests, left to each gallery, over a century ago, by the collector Henry Vaughan, with the proviso that they can only be displayed during the month of January to protect the works. The galleries have honoured these requests and Turner in January has become a tradition in both cities, always popular, with many people returning each year. Vaughan’s collection was comprehensive and he divided it so that each gallery has a coherent collection, representative of Turner’s output.

The watercolours are shafts of light and colour in the depths of winter, as if the sun has come out. The experience of viewing them is intense and quite emotional, and hugely pleasureable. There is something about the annual January show which adds to the sense of occasion, of sharing a special pilgrimage, before their light goes out for another year.

love this post, M. i myself truly love watercolor, since my own grandfather was a watercolor artist, and (in my mind) mastered it quite well. it is an unforgiving medium in which you need precision and speed (and LOTS of practice). i just think alot of people don’t realize that! i agree that their fragility lends a “lesser” feel to them, compared to oils or acrylics, but i’ve never felt that way. (also nowadays, watercolors are just considered “children’s” paint – their first introduction to art and what they start painting with as toddlers. well, obviously, because what mother in her right mind wants to clean up oil paints?? 🙂 )