Monday, February 13th, 2012

The Sting of Love

Happy Valentine’s Day! I thought that this year I would highlight slightly different theme: the sting of love. The material for this post formed over several weeks, partially due to some conversations on Twitter with H Niyazi (of Three Pipe Problem) and Agnes Crawford (of Understanding Rome). Our conversation was sparked by some discussion in one of my earlier posts, which examined whether Fragonard depicted a dolphin or a beehive in his painting The Swing (1767).

In some tweets, Agnes Crawford pointed out that cupid has been depicted with a beehive in many instances. As far as I have found, Dürer’s Cupid the Honey Thief (1514, see above) is the earliest known example of this subject matter in a Northern European context. This association between Cupid and the bee goes back to a fable which is found in the Idylls (which historically has been attributed to the Greek poet Theocritus, but such attribution is unsubstantiated). In this little story, Venus compares her son to a bee and laughs, “Are you not just like the bee – so little yet able to inflict such painful wounds?” Here’s a translation of Idyll XIX:

When wanton Love designed to thieve,

And steal the Honey from the Hive,

An impious Bee his Finger stung,

And thus reveng’d the proffered Wrong.

He blew his Fingers, vex’d with Pain,

He stamp’d and star’d, but all in vain;

At last, unable to endure,

To Venus runs, and begs a Cure,

Complaining that so slight a Touch,

And little Thing, should wound so much.

She smil’d, and said, how like to thee,

My Son, is that unlucky bee?

Thy self art small, and yet thy Dart

Wounds deep, ah! very deep the Heart.

You can see an older English translation of the poem here. A similar poem by Anacreon (which is more witty, in my opinion) is found here.

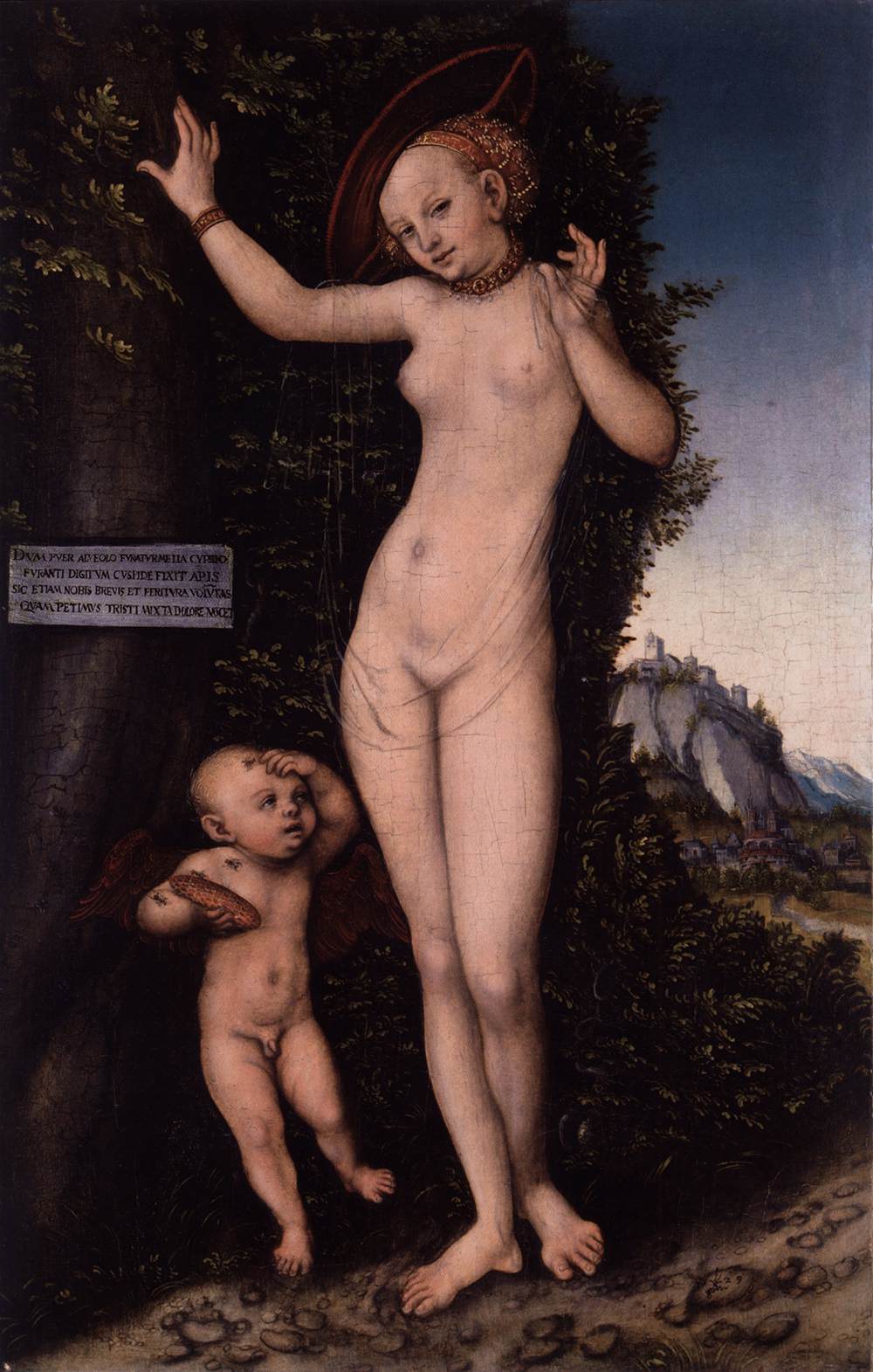

It seems that this story was especially popular in Germany during the Renaissance. Two Latin translations of “Idyll XIX” were published in 1522 and 1528.1 One such translation copy was made by the humanist Johann Hess, who included the manuscript note “Tabella Luce” (“Picture by Lucas”). It is possible that Hess was referring to a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Cranach made his first version of Cupid and the Bee story in 1526-27. Some estimate that Cranach made at least twenty-five versions of this subject matter. Here are a few of my favorite Cranach variations on this theme:

Want to see another version by Cranach? Here’s Venus and Cupid (1531) from the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels. (And if you know of another version, please share in the comments!) It seems like this type of painting was so popular during Cranach’s day because of the moralizing message (which fit with Protestant sensibilities): there is no pleasure without pain.

That being said, I hope that your Valentine’s Day (with your own honey!) is more pleasurable than painful. But if this doesn’t end up being the Valentine’s Day of your dreams, never fear. Cupid can commiserate with you about the sting of love.

1 You may have noticed that the Latin translations I mentioned actually post-date Dürer’s 1514 watercolor by almost a decade! Dürer undoubtedly became familiar with this poem through his friend Willibald Pirckheimer, and even provided illustrations of a text (thought to be by Theocritus) for his humanist friend.

Super post M! I was wondering if you were going to follow this up after our ongoing tweeted exchanges 🙂

For all things Cranach, you must remember we have a superlative resource now: http://cranacharchive.org/

I’m wondering about a possible Southern variation of this – none other than Botticelli’s “Venus and Mars” – which you will of course recall has links to Poliziano’s “La Giostra” – but also contains some bees! Some argue it is a symbolic device to denote the Vespucci family, but it equally fits the “sting of love” theme alluded to here – not to mention the spent looking Mars, possibly also intoxicated by that mysterious fruit(?the squirting cucumber) the putto is holding.

Kind Regards

H Niyazi

3pipeproblem

Is that why we give each other sweets on Valentine’s Day? *she said, stuffing her face with chocolate*

Great post! Idyll 19 on the honey thief is probably classical but its ascription to Theocritus is almost certainly false. Its author is best regarded as anonymous.

Best,

Bob

Thanks for the Cranach resource, H! What a great site!

Your comment about bees and the “sting of love” in Italy makes me wonder if there are other classical documents which might allude to this theme (apart from the “Idylls”). I haven’t found any in my research, but I wouldn’t be surprised if more exist.

heidenkind: I like to think that there might be a connection between sweet honey and the sweets that we eat on Valentine’s Day. I’m not sure if there is a connection, but that’s a fun thought!

Bob: Thanks for pointing that out. I’ve tweaked my post to mention Theocritus, but to separate the poem from a fixed attribution.

In the list prepared for my fourth Topical Catalogue ‘The German-Swiss and Central European Venus’ I have 28 paintings of Lucas Cranach the Elder (including works attributed to him, his workshop or his circle) with this title. Those interested can contact me for details and images of 22 of these paintings.

It is indeed remarkable that the theme was almost exclusively popular in Germany during the 16th century. Few later artists (Kauffmann, Tischbein, Rehberg)were inspired by the theme. Among the 364 works depicting ‘Venus and Cupid’ by identified artists of the Low Countries (see my third Topical Catalogue which can be downloaded for free on my website), I compiled only one work: a drawing by Dirck De Quade van Ravesteyn of 1604-08, after the drawing by Dürer (above). This drawing is in Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv.314 (reference R9703.1252 in my catalogue).

Among the French artists (my second Topical Catalogue) I found two paintings, both exhibited at the Salon Saint-Luc in Paris, one in 1756 by Cornu and one in 1762 by Clermont. But there are no images of these works and thus we do not know if they imitated Dürer or Cranach.

K. Bender: Thank you for your comment! It sounds like your topical catalogues would be a great resource for further information on this topic. It’s interesting to observe (based on your comment) that this theme extended beyond the Renaissance and influenced artists in the 17th and 18th century.

Your site looks very interesting!

I want to say that you have a wonderful blog here.

I’m so glad I came across it!

I am trying to research the fable of Cupid and the bees. Several people online extend the story from Idylls adding that Cupid then shot arrows into the roses (to hit the bee) and those which hit the stems caused the first thorns to grow.

Has anyone any idea whether this is an actual part of the story’s evolution through history, or just a recent addition?