Wednesday, November 17th, 2010

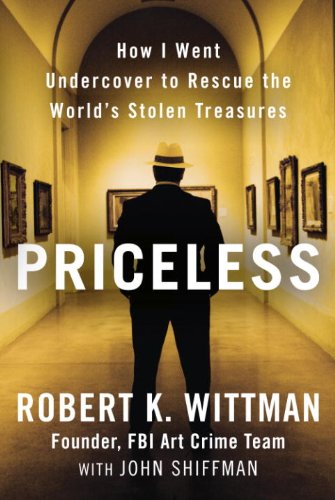

"Priceless" by Robert K. Wittman

I recently finished reading Robert K. Wittman’s book Priceless: How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World’s Stolen Treasures. I had waited several weeks (months?) to get my hands on a library copy of this book, and became even more anxious after reading this great review of the book on Truth, Beauty, Freedom and Books.

The wait paid off, though. Not only is this book entertaining and informative, but it also gives a really interesting perspective on art. As an undercover FBI agent, Wittman has to be informed about the historical significance of the art in his cases, but it is also clear that he views art as objects and historical artifacts. There definitely is nothing wrong with this perspective, and it is a logical perspective for Wittman (since he’s interested in recovering a physical object that has been stolen).

Anyhow, it was interesting to think about Wittman’s apparent “art as object” perspective, since art historians sometimes forget that a work of art is, in its essence, an object: art is paint on a canvas, a block of marble, or metal. I think art historians often “mysticize” or elevate works of art to the point that the objects are exempt from their actual physical properties. Gombrich, for example, tried to humanize art by comparing it to the complexity of “real human beings” (see here). In some ways, I don’t have issue with this perspective either, but it’s interesting to think about how art historians sometimes divorce themselves from the physicality of the art they discuss. But I digress. The point is: it was interesting to see Wittman approach art from a different (more practical?) perspective than I usually encounter among art historians and critics.

Although I would have enjoyed reading more about the historical background for some of the art pieces, Wittman provided a decent amount of information. (Also on a side note, Wittman also works to recover historical artifacts, such as an original copy of the Bill of Rights. These cases are also interesting, but I assumed beforehand that I would only be reading about stolen fine art.)

I especially was interested in reading about the theft of Norman Rockwell’s Spirit of ’76 (1976, shown right).1 This painting was stolen from a gallery in 1978 and was never recovered. The FBI closed the case a few years after the theft, but the case resurfaced in the mid-to-late 1990s, when it became known that the painting had was in the possession of an art dealer in Rio de Janeiro. Wittman was deeply involved in this case by the time of 9/11. Unsurprisingly, the interest in Rockwell and Americana surged after 9/11, due to the rise of patriotism in the American people. Therefore, a whole new dimension and meaning was added to this case, given the 9/11 happenings and interest in Rockwell. And, even more interestingly, Rockwell’s Spirit of ’76 includes an image of the “Twin Towers” (shown in the bottom right corner of the painting). In fact, the inclusion of the “Twin Towers” helped give impetus to finishing this case and recover the artwork from Brazil: officials realized it would be a great public relations move.2

I’d recommend this book to anyone who likes art crime. I think Americans will find the cases especially interesting and meaningful, since Wittman recovered many objects that are significant to American history. However, there are several European pieces that Wittman also recovers/mentions. Really, though, I think that this book would appeal to most people who are interested in art and art crime.

1 I can’t help but add that Rockwell’s composition was inspired by Archibald Willard’s classic Spirit of ’76 (“Yankee Doodle,” the linked version dates c. 1875)

2 Robert K. Wittman, Priceless: How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World’s Stolen Treasures (New York: Crown Publishers, 2010), 174.

Thanks for the mention, M! I'm trying to convince the art school they need to book Wittman as a guest speaker. Don't think it will happen, but it doesn't hurt to ask.

I think art historians do tend not to think of paintings and other fine arts as art objects, partially because we don't usually interact with the pieces themselves. We see pictures of them and read about them in books, and see slides of them, but in essence these art pieces are just ideas in our heads garnered from books and photographs until we actually see them in person. For Wittman, who is pursuing the objects themselves and not the ideas behind them, it is much more about the object. Personally, I kind of liked the mixture of fine art and historical objects in the book, even though like you I was expecting more fine art pieces.

Very interesting M! Art crime is a fascinating area.

I must admit, I also view art as objects too – but in a different sense than Heidenkind has described.

I hate the physical and spatial limitations of having a work stuck in one place, and institutions spending ridiculous amounts of money on them – which quite frankly would be better spent on education and infrastructure.

As evidenced by the poor remainder of art from antiquity, paint is not a durable medium. Eventually, even Renaissance works are going to be so thoroughly restored that there won't be anything left of the original.

Hence, I'm all for technologies that remove the burden of time and geography on art, and instead focus on the skill, beauty and message.

H

Sorry for the late reply to these comments! I thought I had replied earlier, but I was mistaken.

heidenkind: I agree – art historians have a different perception of art since we don't interact with the objects themselves. For us, I think art is more about ideas. And even when we discuss the physical properties of a work of art, we still think about those properties in a non-material way (i.e. words and ideas).

H Niyazi: You've brought up some interesting ideas about technology, skill, message, etc. I can see what you're saying. I think I vacillate between wanting to preserve the message and preserve the physical object. As a writer about art, I want to preserve the ideas and message of the art. But the historian in me also wants to have some tangible object that still exists in the world – not because I'm interested in a tangible or tactile experience with the object, per se, but so that contemporary society will have some connection to the past via the object.