Monday, March 9th, 2009

Intro to Survey Posts & Paleolithic Art

About two weeks ago, I had a friend mention to me that she loves reading my posts but she knows nothing about art. “Where do I start?” she asked. I couldn’t really pinpoint a good place to start on my blog; I write about works of art or articles that interest me, but I don’t include a lot of introductory or survey information. I’ve been looking for some websites that I could recommend to art neophytes, but I haven’t found anything yet that impresses me. So, I have decided to occasionally write some introductory posts. I will try to write in chronological order so that one can get a scope of historical progression by looking at posts under the “introductory/survey” label. I also plan on making an art history timeline that can be viewed/downloaded from this site. Hopefully these posts will be helpful and less-intimidating to newcomers to art history. I hope that the comments for these posts can not only include dialogue and feedback (any art historians are welcome to chime in!), but also be a question and answer forum. I think it will also be good for me, because I can continually review and refine my lecture notes. However, I should also mention that these posts will not be any substitute for an art history survey or art appreciation course. I plan on only writing about works of art and historical information that I find especially interesting!

Some of the earliest examples of art date about 30,000 BC. The Paleolithic (“paleo” = old, “lithic” = stone) people were the first to create representations of humans and animals. One of my favorite Paleolithic sculptures is the “Venus of Willendorf” (ca. 28,000 – 25,000 BC). This little  statuette is only about four inches tall, and her navel is actually a natural indentation of the rock (it was not carved). The purpose and meaning of this statue is not clear (we obviously don’t have a lot of information about paleolithic people), but many think that the exaggerated anatomical features suggest that this statuette is a fertility figurine. There is particular emphasis on the breasts, belly, and pubic area. This preoccupation with fertility makes sense, since the survival of prehistoric peoples would have depended on the fertility and child-bearing capabilities of women. Furthermore, it seems that this statue was not supposed to represent a specific individual, since there are no facial features included.

statuette is only about four inches tall, and her navel is actually a natural indentation of the rock (it was not carved). The purpose and meaning of this statue is not clear (we obviously don’t have a lot of information about paleolithic people), but many think that the exaggerated anatomical features suggest that this statuette is a fertility figurine. There is particular emphasis on the breasts, belly, and pubic area. This preoccupation with fertility makes sense, since the survival of prehistoric peoples would have depended on the fertility and child-bearing capabilities of women. Furthermore, it seems that this statue was not supposed to represent a specific individual, since there are no facial features included.

The thing I love about this statue are the itty-bitty, tiny arms that rest on top of the Venus’ breasts. They are so dainty and petite in comparison to the rest of the body!

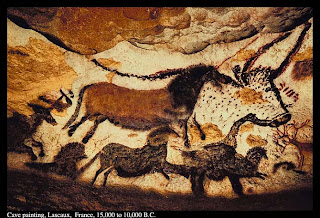

There are many cave paintings which date from the Paleolithic period. Some of the most popular cave paintings of bison are found in Lascaux, France (ca. 15,000 – 13,000 BC).  Some of these bull paintings are quite large – the largest bull is over eleven feet long! These caves were discovered in the 1940 by some teenagers who were outside playing with a dog. For a while, the caves were open to the public, but the amount of visitors (and body heat) raised the temperature within the cave and fungus began to grow inside. In 1963 the cave was closed in order to preserve the paintings. Today, an exact replica of the caves is open to the public, located very near the original site.

Some of these bull paintings are quite large – the largest bull is over eleven feet long! These caves were discovered in the 1940 by some teenagers who were outside playing with a dog. For a while, the caves were open to the public, but the amount of visitors (and body heat) raised the temperature within the cave and fungus began to grow inside. In 1963 the cave was closed in order to preserve the paintings. Today, an exact replica of the caves is open to the public, located very near the original site.

Just as with the “Venus of Willendorf”, we don’t know the exact reasons why these paintings were created. Some think that bulls held some type of religious significance for ancient peoples. It could be that these paintings are located deep inside a cave because they are connected with some type of religious ritual. Horned animals also were associated with fertility in the ancient world, and these paintings be associated with a fertility ritual. You can read more about the caves official website about the caves is found here.

My favorite prehistoric cave drawings, however, are found at Pech-Merle, France (ca. 22,000 BC). These drawings depict a spotted horse, and it is possible that the spots (which are both inside and outside the horses’ outlines) were created by the artist throwing painted rocks  at the cave wall. The thing I love most about this cave, however, are the human hand prints. These hand prints are depicted with “negative” space, meaning that the artist placed his hand against the wall and probably blew pigment around it with a hollow reed or bone. The pigment created a “positive” space, and the original “negative” space of the cave wall depicts the hand. Even though animals are the main theme of these paintings instead of humans, I love the inclusion of the artist’s (or artists’) hands.

at the cave wall. The thing I love most about this cave, however, are the human hand prints. These hand prints are depicted with “negative” space, meaning that the artist placed his hand against the wall and probably blew pigment around it with a hollow reed or bone. The pigment created a “positive” space, and the original “negative” space of the cave wall depicts the hand. Even though animals are the main theme of these paintings instead of humans, I love the inclusion of the artist’s (or artists’) hands.

If you are interested in reading more about Paleolithic art, there is a New Yorker article which discusses cave paintings and gives some information about Chauvet cave. Although the date of the Chauvet paintings is debated, this cave possibly houses the oldest cave paintings known today.

I also really like the the hands. I wonder why the artist(s) chose to include them.

I LOVE this post. Thanks for the intro! I agree with you: it’s very cool that the artist has his hand prints in his work … kind of personalizes it, doesn’t it?

Great idea to post some introductory art history Monica – I honestly hadn’t noticed the small arms on the fertility statue! Don’t know how I missed that! I must say that the one book that I learned my art history basics from was The Annotated Mona Lisa by Strickland. After a TERRIBLE AP Art History class my senior year, I basically taught myself by reading/memorizing this book – and managed to get a 4 on the exam! This book is so fabulous, breaking all the “-isms” down into charts, prominent artists and technological or cultural advancements of the time. I think a new edition just came out. That’s where I’d suggest an art history “newbie” start.

Thanks for the recommendation, Joolee! I’ve never read The Annotated Mona Lisa, but this sounds exactly like the kind of thing I need to recommend to art history newcomers. I’ll have to check it out!