Thursday, October 21st, 2010

Call for Entries: The November Issue of the Art History Carnival

Hello everyone! I am happy to announce that I will be hosting the November issue of the Art History Carnival (a carnival which originated on The Earthly Paradise blog). The November issue of the Art History Carnival will be posted on November 1, 2010. You can submit articles to be included in the carnival until 48 hours before the issue comes out. Therefore, please submit your entries to me by Saturday, October 30, 2010.

What is an art history carnival?

A carnival is a type of blog event that is dedicated to a particular topic – in this case, art history. Carnivals appear in the form of a blog post, and they include links to the posts dedicated to that particular topic. Carnivals are like magazines: they are published on a regular schedule. This art history carnival is published on a monthly basis.

This blog carnival is a great way for art historians (and those interested in art) to interact. This carnival also helps us to become familiar with the latest research/thoughts of others. Plus, it’s a great way for bloggers to share their information (and blog!) with other people!

What kind of blog articles are included in the carnival?

Posts covering all artistic periods and mediums are welcome, including posts regarding art criticism, architecture, design, theory and aesthetics. These posts should have been written since the last art history carnival (which was published October 1, 2010), to help ensure that our carnival contains current research/information/thoughts. I promise to carefully review each submission.

Who can submit?

Anyone can submit, providing that they have a blog and an art-related post to share! If you don’t have a blog, you are welcome to submit the post of a friend.

Can I host a carnival?

Yes! Please contact Margaret at The Earthly Paradise for more information.

How to submit articles for this edition:

Please email your submissions to me directly (albertis.window@gmail.com). Your submissions should include the link(s) to the post(s) you are submitting – it is not necessary to include the text of the post(s) in the body of your email.

UPDATE: You may also use the Blog Carnival Submission Form. Margaret updated the form so that the links will be sent to me this month.

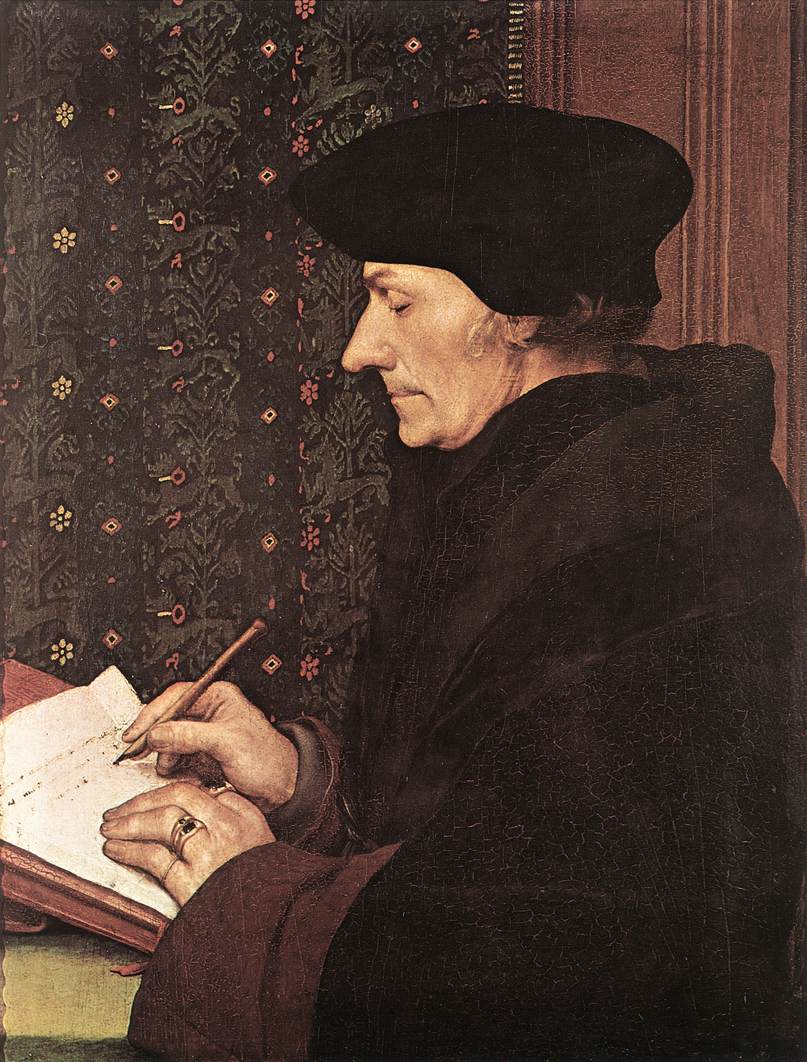

I’m excited to read the submissions! Thanks for letting me host the carnival this month, Margaret. Please share the information about this carnival to anyone who might be interested in reading or contributing to it! And if you haven’t written anything interesting for the carnival, don’t despair: you still have about a week before submissions are due. Sit down (like our friend Erasmus, who was depicted by Hans Holbein in 1523 (see above)) and start writing!