Saturday, July 23rd, 2011

The "Collection Museum"

I have been doing some research on Isabella Stewart Gardner over the past few weeks, in hopes to present something at a conference this fall.

In doing this research, I’ve started to make a compilation of “collection museums” that were created by private collectors in the late 19th and early-to-mid 20th century. I love going to “collection museums,” especially when such buildings also functioned as the residence for the collector. Two of my favorite museum experiences are when I visited the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC (shown right) and visited the Frick Collection (shown below on left).

First of all, I love seeing what types of art appeal to one individual, as a collector. It is also interesting to visit these museums and see how a collector would have potentially “decorated” their residence space. (The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is most interesting in this respect, since she specified in her will that the arrangement and presentation of her collection could not be altered after her death, or the whole collection would be given to Harvard University.)

I think that a museum visitor can make a lot of interesting associations with works of art when they are in such a personal, domestic setting. Although great works of art can undoubtedly stand (or hang!) on their own, I love seeing works of art in an interesting context and display. “Collector museums” are fun to have in a postmodern society, don’t you think? It’s much more interesting to me than the white cube gallery space, that’s for sure.

Here are the “collection museums” that I have compiled so far (in chronological order of when the museums were built/founded):

UPDATE: A more comprehensive list (going outside the time frame from this post) was created in a separate post on this blog.

- The Wallace Collection (London). The collection was mainly amassed by Richard Seymoure-Conway, who bequeathed the collection to his illigetimate son, Sir Richard Wallace. Collection is displayed in the Hertford House, the main London townhouse of Sir Richard Wallace. The collection was bequeathed to the British nation in 1897 by Lady Wallace (Julie-Amélie-Charlotte Castelnau), wife of Sir Richard Wallace.

- Musée Condé in the Château de Chantilly (near Paris). Bequeathed by the Duc d’Aumale to the Institut of France in 1897. (Note: From what I can tell, this museum is not the collection of one private collector, but a collection that was amassed over time by the Montmorency and Condé families. Museum also has a collection once owned by Caroline Murat, the sister of Napoleon.)

- The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston, Massachusetts). Collection of Isabella Stewart Gardner. The museum (“Fenway Court”) also served as Isabella’s residence. Construction begun in 1899, opened to the public on Near Year’s Day, 1903.

- Jacquemart-André Museum (Paris). Collection of André and Nélie Jacquemart. Nélie Jacquemart was a well known society painter. In accordance with her husband’s wishes, Nélie bequeathed the mansion and collection to the Institut de France. Museum opened in 1913.

- The Hallwyl Museum (Stockholm). Primarily the collection of Countess Wilhelmina von Hallwyl. Museum is located in the Hallwyl House, which served as the private residence for Count and Countess van Hallwyl. Collection was donated to the state in 1920.

- The Phillips Collection (Washington, DC). Collection of Duncan Phillips. Museum building was once Phillip’s residence. Founded 1921.

- Sinebrychoff Art Museum (Helsinki, Finland). Collection of Paul Sinebrychoff. Collection donated to the state in 1921. The Sinebrychoff private residence (the current location of the museum) was bequeathed to the state in 1975.

- The Barnes Foundation (originally located in Merion, Pennsylvania). Collection of Albert C. Barnes. Founded in 1922. I’m especially distraught over this museum, since the collection is currently being moved to a new location in Philadelphia. If you want to learn more about the situation involving the displacement of the Barnes Foundation, I’d recommend that you see the documentary The Art of the Steal.

- Freer Gallery of Art (Washington, DC). Collection of Charles Lang Freer. Construction begun in 1916, but gallery completion was delayed because of WWI. Gallery opened in 1926.

- Benaki Museum (Athens). Collections of Antonis Benakis. Founded in 1926.

- The Huntington Art Gallery (Pasadena, CA). Collection of Henry E. Huntington. Museum building was once Huntington’s residence. Opened in 1928.

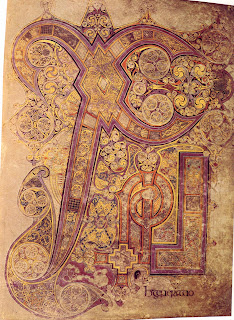

- Musée Marmottan Monet (Paris). Originally the collection of Paul Marmottan (which was partially inherited from his father, Christophe Edmond Kellermann, Duke of Valmy). Museum was bequeathed to the Académie des Beaux Arts. The museum location originally served as the hunting lodge for Christophe Edmond Kellermann and later the home of Paul Marmottan. The Academy opened the museum in 1935. Museum collection was expanded with a gift in 1957 (Impressionist collection once owned by Doctor Georges de Bellio) and in 1966 (the personal collection of Claude Monet, bequeathed by Monet’s son Michel Monet). Museum also houses a collection of illuminated manuscripts once owned by Daniel Wildenstein (who died in 2001).

- The Frick Collection (New York City). Collection of Henry Clay Frick. Museum is housed in the former home of Henry Clay Frick. Museum opened to the public in 1935.

- The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art (Sarasota, Florida). Collection of John and Mable Ringling. Museum functioned as the Ringling family’s private residence. Art collection, mansion, and estate were bequeathed to the state of Florida in 1936, at the death of John Ringling. This museum boasts an eclectic Baroque collection, among other things.

- Maryhill Museum of Art (Goldendale, Washington). Collection of Sam Hill and Loïe Fuller. Construction of mansion (current location of museum) was begun in 1914 by owner Sam Hill. However, construction stopped in 1917. Work resumed in 1920s and 1930s, with the intent of turning the mansion into a museum. Museum opened to the public in 1940. This museum owns more than 80 works by Rodin.

- Dumbarton Oaks (Washington DC). Collection of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss. Museum also functioned as residence for the Bliss family. Institution dedicated and transferred to Harvard University in 1940.

Know any more to add to this list? Have you been to visit any of these places? What was your experience? I learned about several of these lesser-known museums from a book review of A Museum of One’s Own by Anne Higonnet. I hope to read Higgonet’s book this week and add more museums to my list.

I think it’s really interesting that several women were among the first to convert their private residence into a museum space, including Lady Wallace (Wallace Collection) and Isabella Stewart Gardner. Many other women were key in forming collections, such as the Countess Wilhelmina van Hallwyl (Hallwyl Museum) and Loïe Fuller (Maryhill Museum of Art). Perhaps there was something about displaying art in a domestic space that was especially appealing to female collectors? I think that I might explore this idea further in my research!

Images from Wikipedia. Frick Collection image by Wikipedia user “Gryffindor.”