Saturday, September 3rd, 2011

Feathers and Colonialism

Over the past few days I’ve been thinking a lot about Amerindian featherwork and colonialism. Probably the best-known examples of featherwork are the “feather paintings” produced by Nahua featherworkers (who were called amanteca). The Aztecs, a branch of the Nahua people, used featherwork for a wide range of prestigious items, including tapestries for their palaces, capes, and head crests.

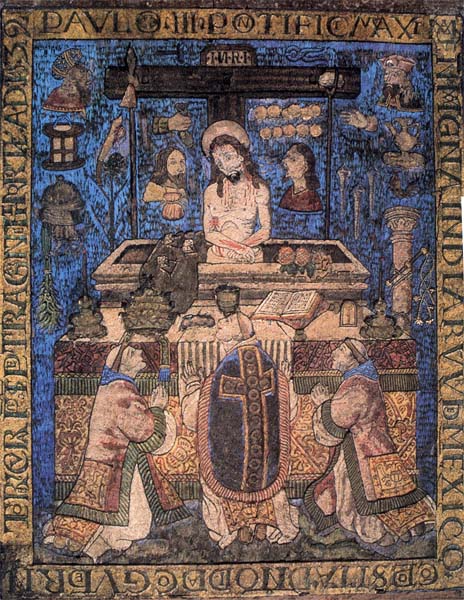

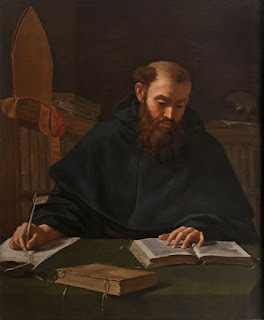

I’m particularly interested in what happened to featherwork after the Europeans came to the Americas. For one thing, Aztec artisans were commissioned to create “feather paintings” in the European style. A Nahua ruler, Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin, commissioned The Mass of Saint Gregory (shown above) as a gift for Pope Paul III.1 From a postcolonial standpoint, it’s interesting to see how the use of European style can be interpreted as an expression of European control. Gauvin Alexander Bailey points out that European “friars wanted to harness this native tradition in the service of Christian propaganda and benefit from the prestige enjoyed by such featherwork in the pre-Hispanic era.”2

Along these lines, Europeans also were fascinated with feather paintings, not only for their technical skill, but apparently for their delicacy.3 I think that this idea of delicacy and fragility is very interesting, given the context of colonialism. With the European mindset of conquering the Amerindians (in terms of politics, culture, and religion), it doesn’t seem surprising that the Europeans would be drawn to imagery that reinforces the delicacy and fragility (in other words, the weakness) of the Amerindians. And I think it is especially interesting that the this idea of fragility is not necessarily embodied in the subject matter for the imagery, but in the artistic medium itself.

Undoubtedly, the feather medium also was a source of exoticism to European viewers. The feathered cloaks of the Tupinambá people (an indigenous group of Brazil) “were collected as objects of curiosity and wonderment by Europeans.”4 No doubt that this sense of wonderment was brought about by the “difference” and “Other-ness” of these objects. Even today, these cloaks continue to instill a sense of awe in European viewers by virtue of their rarity – today only seven such objects remain in European museums. (An image and discussion of the cloak in the Royal Museum of Art and History (Brussels) is found here.)

In fact, the act of collecting featherwork also can be connected to the conquering mindset of Europeans and colonists. One can argue that Europeans were able to “own” or “control” Amerindians through the collection and ownership of feather art. Works of art can be transported, manipulated, bought, contained (think of the Cabinet of Curiosities in the 16th and 17th centuries), and sold – similar to how the Amerindians were treated by various European groups.

1 This feather work copies the composition and details of a 15th century German engraving, Mass of Saint Gregory by Israhel van Meckenem.

2 Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Art of Colonial Latin America (London: Phaidon, 2005), 104.

3 Ibid., 105.

4 Edward J. Sullivan, “Indigenous Cultures,” in Brazil: Body and Soul (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2001), 78.

Image credit: Public domain image via Wikipedia.