Tuesday, April 3rd, 2012

Excavation Sites for Prehistoric and Ancient Female Figurines

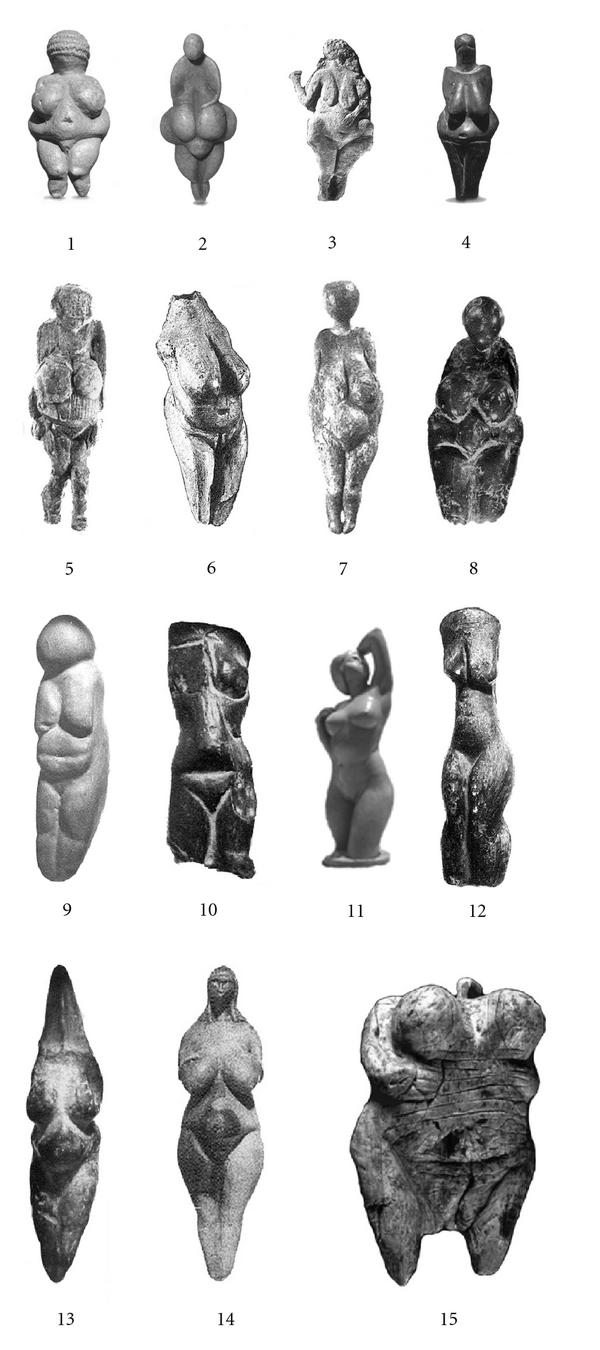

Various (mostly) prehistoric “Venus” figurines. (1) Willendorf’s Venus (Rhine/Danube), (2) Lespugue Venus (Pyrenees/Aquitaine), (3) Laussel Venus (Pyrenees/Aquitaine), (4) Dolní Věstonice Venus (Rhine/Danube), (5) Gagarino no. 4 Venus (Russia), (6) Moravany Venus (Rhine/Danube), (7) Kostenki 1. Statuette no. 3 (Russia), (8) Grimaldi nVenus (Italy), (9) Chiozza di Scandiano Venus (Italy), (10) Petrkovice Venus (Rhine/Danube), (11) Modern sculpture (N. America), (12) Eleesivitchi Venus (Russia); (13) Savignano Venus (Italy), (14) The so-called “Brassempouy Venus” (Pyrenees/Aquitaine), (15) Hohle Fels Venus (SW Germany). Image from article, “Venus Figurines of the European Paleolithic: Symbols of Fertility or Attractiveness?” by Alan F. Dixson and Barnaby J. Dixson (2011).

Yesterday I had a student ask about the excavation sites for so-called “Venus” figurines from the Paleolithic period. This student wondered if the physical location of the site (or the other objects excavated at the sites) could give us more understanding about how the “Venus” figurines originally functioned. I thought this was a great question. Although I knew that some figurines were found in caves or domestic sites, I thought that I would find more information about the specifics regarding the excavation sites and findings.

I didn’t find nearly as much information as I had hoped (there may be more information hidden away in technical archaeology journals), but I did pull together a few interesting finds. It is interesting to see how several figurines are associated with domestic sites or found alongside animal bones. Would these bones have been food for these people or sacrifices for religious rituals? Perhaps both? Other female figurines are found in caves, sometimes with other objects and animal bones, too.

I know that the following list isn’t comprehensive by any means. (I also threw a Neolithic and a Minoan female figurine in the list, just to make things fun.) I plan on adding to this list as I come across new information and findings. If you want to add a another figurine to the list, or more details regarding the excavation of these figurines, feel free to leave a comment!

Photograph of the Hohle Fels Cave. Red arrow indicates where the “Venus” of Hohle Fels was discovered in September 2008.

- Venus of Hohle Fels (at least 35,000 BCE) : Excavated in September 2008 in the Hohle Fels cave in Germany (see image above). The figurine, which was carved from a mammoth’s tusk, was discovered in six fragments. A flute was also discovered at this site, which currently is the oldest known instrument in the world.

- Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000 − 25,000 BCE): Discovered in 1925 in a layer of ash. The figurine was broken into two pieces. Figures of animals, as well as 2,000 balls of burnt clay, have been found at the Dolni Vestonice site. The majority of these finds were located at the dugout of central fire pit at the site.

- Venus of Laussel (20,000 − 18,000 BCE): Discovered in 1911 by physician J. G. Lalanne. The figure is found in a rock shelter, carved onto a piece of fallen limestone.

- Venus of Willendorf (28,000 − 25,000 BCE): Excavated in 1908 by Josef Szombathy in a loess deposit (fine-grained material that has been transported by the wind). More technical information about the excavation and layer deposit is found here.

- “Venus II” from Willendorf (see suggested reconstruction here): Discovered in 1926 by Joseph Bayer. This figurine was found in a pit, lying on top of the jaw of a mammoth. This figurine is probably older than the “Venus of Willendorf.” The deep pit where “Venus II” was found went from level nine to level five. The original “Venus” of Willendorf was excavated at level nine.

- Venus of Brassempouy (c. 23,000 BCE): Discovered in 1894 in Pope’s Cave (Brassempouy). The figure was discovered with at least eight other human figures. There has been some confusion with the chronology of the site findings, since the site was pillaged and disturbed beyond recognition by a group of amateurs on a field trip in 1892.

- Venus of Lespugue (24,000 − 22, 000 BCE): Discovered in the cave of Lespugue in 1922.

- Gagarino Venus (c. 20,000 − 1,700 BCE): Excavated between 1926-1929. These figures were found in a house pit. The walls of the pit were lined with rhinocerous and mammoth bones.

- Kostenki Venus (23,000-21,000 BCE): This term is actually a misnomer (beyond the already-problematic nickname of “Venus”) since there was a group of “Venuses” discovered at this site. The most famous one, however, is an mammoth-bone statuette discovered in 1957 by Zoya A. Abramova. Kostenki refers to 20 Paleolithic sites along the Don River in Ukraine.

- Seated Mother Goddess of Catal Huyuk (7th century BCE): Excavated from the upper levels of the site by James Melaart in 1961. Figurine was found in a grain bin.

- Minoan “Snake Goddess” (c. 1600 BCE): Discovered in 1903 by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. One of the “snake goddess” figurines was located at the “palace” of Knossos in a cist (repository) on the floor of a small room (near the “Throne Room” and “Room of the Charior Tables”). Sir Arthur Evans believed that this snake goddess (and the other objects found in the cist) formed part of a cult shrine. Evans identified the figurine traditionally identified as a “Snake Goddess” in art history textbooks as a votary of the snake goddess.