Saturday, September 1st, 2012

Gothic Cathedral as Body and Mountain

This past week I read a really interesting article by Peter Fingesten: “Topographical and Anatomical Aspects of the Gothic Cathedral.”1 Fingesten feels like the form and design of Gothic cathedrals have allegorical and symbolic meaning. He compares the interior of cathedrals to the anatomy of the human body (in essence, as symbols of Christ and/or the Virgin Mary). He also compares the exterior of cathedrals to mountains, finding a link between Gothic cathedrals, the Heavenly Jerusalem, and the “sacred mountain imagery” that existed in ancient cultures. This imagery, according to Fingesten, is largely inspired by the John the Revelator’s visions of the Heavenly Jerusalem (Chapter 21 of the Book of Revelation). I thought I’d briefly mention a few of the main points here.

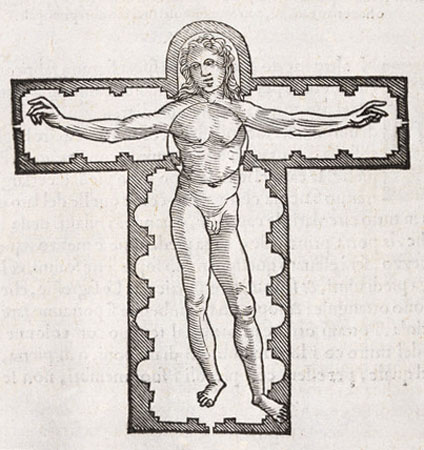

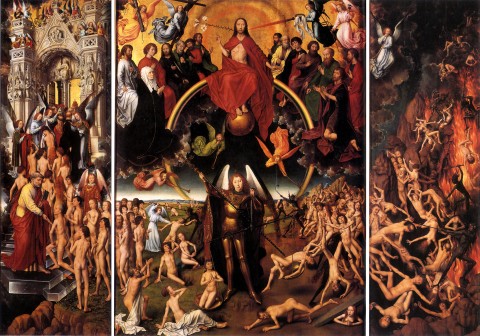

Before reading this article, I already was familiar with how the floor plan of a basilica can mimic the form of the cross, or even the body of Christ. The allegorist William Durandus (also sometimes written Guillaume Durandi or William Durand) said as much in the 13th century. Fingesten asserts this point, and even references Vitruvius and the Renaissance artist Pietro Cataneo’s “Vitruvian Figure”(1554, see above), which is depicted within the basilica floor plan. But Fingesten takes things further: he discusses how the ribbed vaults of cathedrals mimic the spinal cord and ribs of a human figure. He believes that the Lincoln Cathedral interior (shown at the beginning of this post) is the best expression of this anatomical imagery. Fingesten also believes that the stained glass windows represent the translucent skin of the human body.

Using biblical references, Fingesten argues that the cathedral interior was originally intended to symbolize the body of Christ (who is recorded in the New Testament to have compared his own body to a temple). With the increase of devotion to the Virgin Mary in the twelfth century and afterward, the cathedral also came to symbolize her body. Mary’s body (and womb) traditionally have been compared to a “temple of God,” so I think that this later reinterpretation of the cathedral (really, a merger of male and female allegories) makes sense. I was especially intrigued by Fingesten’s descriptions about how “the pointed ribbed vault system suggests the rib-cage of a gigantic mother bending over her son” and how “cathedrals increased in size until they bulged like a woman high with child.”2

Salisbury Cathedral, England. Church building 1220-1258; west façade finished 1265; spire c. 1320-1330; cloister and chapter house 1263-1284

Fingesten also analyzes the exterior of cathedrals, finding that they symbolize the Heavenly Jerusalem, which is set upon Mount Zion. Fingesten thinks that this sacred mountain imagery is evoked in several ways. He finds that mountain peaks are referenced in the crossing tower and facade towers, while the spires allude to the summit.3 Nature is evoked in the exterior decoration through details and niches, recalling the weather-beaten appearance of a mountain.4 Even the flying buttresses are used to extend this symbolism, Fingesten argues, and describes how they “hang precariously like snow bridges and drifts from the cliffs of the nave elevation.”5

It’s a really interesting and unique argument, I think. Fingesten delves into some textual references (beyond the Book of Revelation) to back up his argument. I’m not going to delve into those here, but you are welcome to read the argument on your own. My main concern is that Fingesten doesn’t convincingly have his own argument align well with what Durandus wrote in the 13th century. (For example, Durandus compared stained glass windows to the scriptures, not to translucent skin.) That being said, though, I think Fingesten’s interpretation of the cathedral is very impressionable. I know that I’ll think about rib-cages and mountains the next time I visit a Gothic cathedral.

1 Peter Fingesten, “Topographical and Anatomical Aspects of the Gothic Cathedral,” Journal of Aesthetics and Criticism 20, no. 1 (1963): 3-23.

2 Ibid., 18.

3 Ibid., 8.

4 Ibid., 10.

5 Ibid., 9.