Monday, June 24th, 2013

Student Research on Bernini and Caravaggio

One of my favorite courses that I taught this past academic year was an upper-level class on the art of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. My students were required to write research papers with original arguments on topics of their choice. I was pleased to see that two of my students, Peg Anderson and Chloe Froom, were undaunted by the mounds of already-existing research for two popular Baroque artists, Bernini and Caravaggio. They have given me permission to share a little of their research and arguments here. I’m pleased that I got to play a small role in helping these students approach these topics, but the original arguments and ideas were entirely their own.

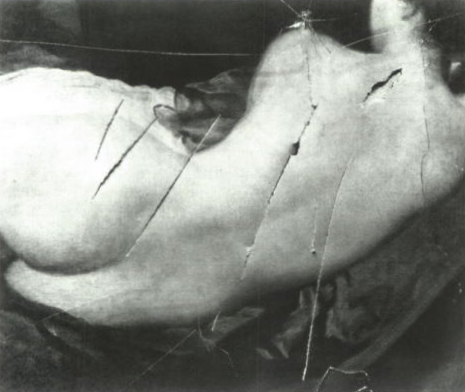

Left: Caravaggio's "Saint Matthew and the Angel," 1602 (destroyed 1945). Right: Bernini, "Habbakuk and the Angel," 1655-61 (Chigi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome)

My student Chloe Froom argued that Bernini was deliberately influenced by Caravaggio when Bernini created Habakkuk and the Angel for the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo. The composition and subject matter of Habbakuk and the Angel is very similar to Caravaggio’s painting, Saint Matthew and the Angel (also known as the first version of The Inspiration of Saint Matthew). As can be seen through a direct comparison (see above), Bernini seems to deliberately mimic the extended leg of Caravaggio’s figure of Saint Matthew; this leg projects forward into the space of the viewer. Additionally, both works of art include an angel who lightly and lyrically extends an arm to engage in the the slightest bit of physical contact with the seated figure. Froom writes, “In both works, the angels are covered in delicate drapery [that is] revealing of their forms. There is a deep slit beginning at the top of the hip that continues to reveal the entire leg. Their abdomens are also exposed, Caravaggio’s caused by the sheerness of the fabric and Bernini’s by the parting of drapery.”1

At the time of Bernini’s commission for the Chigi Chapel, paintings by Caravaggio already were in place in another chapel within Santa Maria del Popolo, the Cerasi Chapel (namely, The Conversion of Saint Paul on the Road to Damascus and The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, which both date 1600-1601). Perhaps Bernini sought to create aesthetic continuity within these two Santa Maria del Popolo chapels by honoring Caravaggio’s style. It is almost certain that Bernini would have been familiar with Caravaggio’s painting Saint Matthew and the Angel. After this painting was rejected in 1602 for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, it immediately entered the collection of the wealthy collector Vicenzo Giustiniani. Froom explains, “In 1590 the Giustiniani family bought the palazzo opposite S. Luigi dei Francesi and created the Palazzo Giustiniani. The family also had a villa outside the Porta del Popolo, where Bernini created his sculpture Habakkuk and the Angel. The Palazzo Giustiniani, along with their other villas, were filled with the family’s vast art collection and became a popular destination for many artists until the late 18th century. It is therefore, a definite possibility Bernini went into the Guistiniani Palazzo and villas…because he worked in close proximity to them.”2

Peg Anderson argued in her research that Bernini’s personal relationship with some of his patrons affected the way in which the figures were represented. For example, Anderson finds that the portrait of Cardinal Scipione Borghese depicts the figure in a very positive light, despite Borghese’s overweight frame. Such positive features include the relaxed, slightly-cocked head, and the soft, yet penetrating gaze of the sitter. Anderson also explored how Borghese was Bernini’s first major patron of the arts; this supportive and close relationship accounts for why Bernini cast his sitter in a positive light. In fact, Anderson even argues that the slightly-undone button in the cardinal’s clothing, is really a playful gesture (perhaps a sign of endearment, I think one could argue) on Bernini’s part.

Anderson writes, “He creates an accurate depiction of the sitter, however he portrays Scipione with the persona he would have wanted [contemporary] Romans to believe he possessed. In the Bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, Scipione the model appears to be spirited, approachable, and perhaps celebrated. Yet some accounts of Scipione differ from this depiction. The man was described by author Franco Mormando as ‘ruthless as any sociopath in his mad pursuit of money, power, and pleasure.'”3

For contrast, Anderson explored how Bernini had a negative relationship with Innocent X, which stemmed from Bernini’s ill-fated towers for Saint Peters. The towers were completed in 1644, although they were unstable and a crack had begun to appear before the towers were even completed. Two years later, in 1646, the Pope Innocent X ordered the towers to be torn down. A year later, Bernini completed his bust portrait of the pope, which is less flattering than the one he created of Scipione Borghese.

Anderson argues the following abut the Pope Innocent X portrait: “The sparkle that held the viewer’s gaze in Bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese does not exist, there is not even a glimmer of hope in [this] old man. The eyes are empty, arguably hollow and absent. The furrowed brow only further contributes to the unpleasant facial expression. Bernini is not generous when he reflects the wrinkles he saw on Innocent X’s forehead, and deep creases in between the nose and mouth…the bust is portrayed standoffish, uninterested, inaccessible, and unable to please.”4

I’m proud of Chloe and Peg and the work that they did on this assignment. Their arguments are much more extensive than I have included here, but this post captures their gist of their research. Really, I had several fantastic research papers submitted from students who took my Counter-Reformation course. I wanted to highlight these two papers, though, because I worked quite a bit with these students during their research process and because I love Bernini’s art!

On a side note, people may be interested to see this online compilation of some of Bernini’s portraits. Additionally, if you would like to help ensure that Bernini’s bust of Francesco d’Este is able to go on public view again, you can donate to this fundraiser (there are only a few days left!).

1 Chloe Froom, “Bernini’s ‘Habbakuk and the Angel’ and Caravaggio’s ‘The Inspiration of Saint Matthew,” unpublished, 2013.

2 Ibid.

3 Peg Anderson, “Bernini’s Portraits: Creating a Likeness,” unpublished, 2013. See also Franco Mormando, Bernini: His Life and His Rome (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 46.

4 Anderson, 2013. Anderson finishes her paper by discussing Bernini’s caricature of another pope, Pope Innocent XI. Pope Innocent XI had issues with the figures of “Truth” (and “Charity”) that Bernini created for the tomb of Alexander in St. Peter’s; the pope found the figure’s exposed breasts to be indecent. The sculptures were accordingly modified, but left Bernini upset. As a result, Bernini may have created this caricature of the shriveled, skeletal and weak pope as a personal means to express his frustration.