My family and I just got back from a vacation to England. About three-and-a-half of those days were spent in London, and we were able to cram eight museum visits into those few days! We visited Sir John Soane’s Museum, the Tate Modern, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Wallace Collection, the Design Museum, the National Gallery, the Tate Britain, and the British Museum. I especially loved the elegance of the Wallace Collection, the quirkiness of the Soane Museum, and the grandeur of the British Collection.

I got to see a lot of beloved works of art on this trip, including relief carvings of Ashurbanipal’s lion hunt, the Parthenon Marbles, the hunting scene from the Tomb of Nebamun, and Holbein’s The Ambassadors. I also was really glad that I saw the “Vermeer and Music” show at the National Gallery (even though it meant that I had to sacrifice seeing The Arnolfini Portrait in another section of the museum, due to time constraints!). I also became familiar with new artists and/or works of art during this trip, and I thought I would share them here.

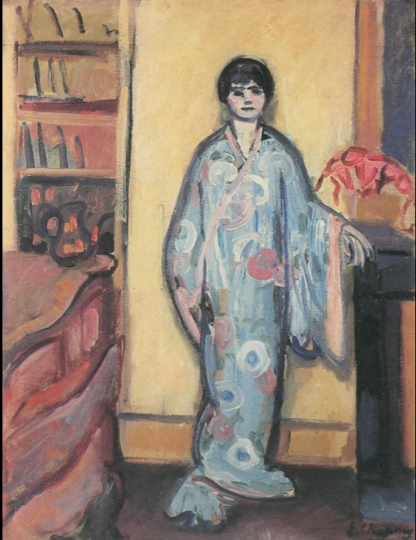

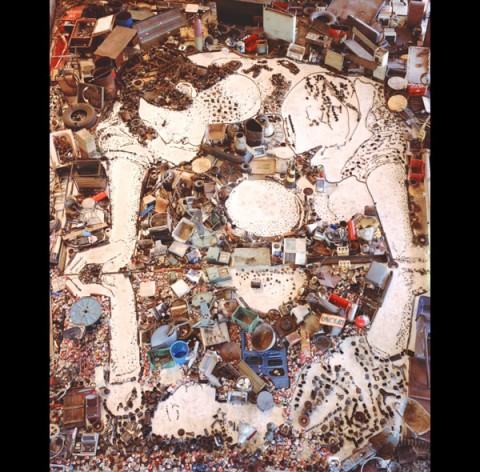

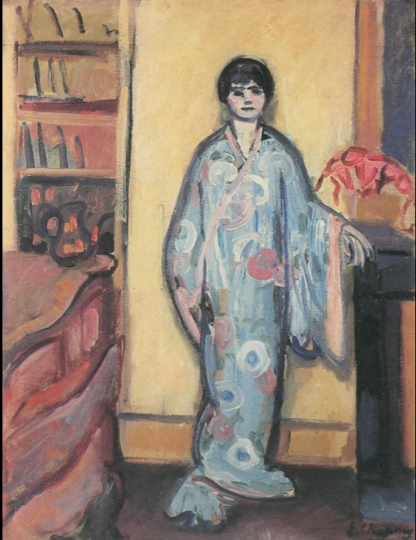

Emilie Charmy, Woman in a Japanese Dressing Gown, 1907. Oil on canvas, 81 x 68 cm. Image from StudyBlue

This isn’t a work of art that I saw in London, but I was introduced to the work of Emilie Charmy on the plane ride to England. Several of her paintings (including Woman in a Japanese Dressing Gown, shown above) are included in Gender and Art, a book that I read while on my trip. In 1921, the critic Roland Dorgelés wrote that that Charmy “sees like a woman and paints like a man.”1 An online gallery of Charmy’s work can be found HERE.

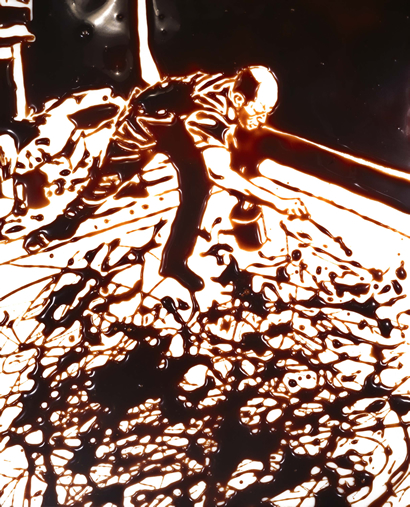

Lee Ufan, "From Line," 1978. Oil paint and glue on canvas. Tate Modern.

Ufan’s From Line is one of the works of art that I saw in the Tate Modern. I love this painting for several reasons, partly because the aesthetic perfectly matches the things that my husband loves about Abstract Expressionism. Ufan wrote this about his method: “Load the brush and draw a line. At the beginning it will appear dark and thick, then it will get gradually thinner and finally disappear . . . A line must have a beginning and an end. Space appears within the passage of time, and when the process of creating space comes to an end, time also vanishes.”2

Fred Wilson, "Grey Area (Black Version)," 1993. Five painted plaster busts, five painted plaster wooden shelves.

I am mostly familiar with Fred Wilson’s interesting exhibition work in Mining the Museum, so I found his piece Grey Area (Black Version) to be a welcome surprise. Plus, I love the Egyptian bust of Nefertiti. Wilson’s piece draws attention to “the claims for Nefertiti, and ancient Egypt generally, as positive examplars of blackness within African American culture, but also on the debates around Nefertiti’s actual racial identity and obscured histories of African peoples, alluded to in the title ‘Grey Area.'”3

Carolingian Ceremonial Comb with Astrological Symbols, c. 875. Victoria and Albert Museum

I was excited to see this liturgical comb in the V&A, largely because my friend Shelley had piqued my interest in liturgical combs with her post earlier this summer. The museum text panel for this Carolingian comb explained, “Combs like this were used to part the hair of the priest before celebrating Mass, and in other ceremonies. This combing symbolically ordered the mind, as well as reducing the risk of falling hair contaminating the wine.”4 The museum website also explains (in a blurb about a 12th century comb) that liturgical combs symbolized “a concentration of thoughts toward the liturgy.”

Cast of the Hildesheim doors (center) in the Cast Courts at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Plaster casts of Trajan's Column, from the Cast Courts at the Victoria & Albert Museum

I was really looking forward to seeing the casts in the Cast Courts at the Victoria & Albert Museum. To my great disappointment, I found that the Cast Courts were closed, and only one of the courts could be seen by looking from a second-story balcony. I was most looking forward to seeing minute details in the casts of the Hildesheim Doors, but I had to try and be content with seeing those doors from a distance. I did feel like I had a new perspective though, on the sheer size of Trajan’s column after seeing the cast placed in an indoor space. Both my husband and I exclaimed in surprise when we stumbled upon the balcony which afforded a view of the column (so large that it is displayed in two pieces!). More information on the plaster casts of Trajan’s Column can be found HERE.

Fragonard's "The Swing" (second from right) and Boucher's "Cupid á Captive" (right) in the Wallace Collection

One of the Dutch Rooms in the Wallace Collection

I wanted to include two images of the Wallace Collection interior, since I felt like the setting for this museum was a work of art in-and-of-itself. If I had to choose, I think that this museum was my very favorite one that we visited on this trip. I wanted to visit this museum and the Soane Museum ever since I began to compile my Collection Museum list, and the Wallace Collection did not disappoint! It was also really fun to see Fragonard’s The Swing, since the first art history paper I ever wrote in college was on that painting. It was a lot smaller than I expected! I also thought it was neat that The Swing and Cupid á Captive hang side by side, since those are two popular works of art that often feature in art history survey courses.

Caspar Netscher, The Lace-Maker, 1664

One of the paintings that was a very nice discovery in the Wallace Collection was Netscher’s The Lace Maker. I feel like this has a really strong composition, but also exhibits some interesting interest in texture (for example, with the intricate cap, the plastered wall, and the paper on the wall). This morning I have been thinking about how the turned body and red clothes of the figure remind me a little bit of the centrally-placed woman in Courbet’s The Wheat Sifters (1854) from the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes collection. In some ways, it’s interesting to compare these paintings and see how Courbet was heir of the Dutch genre painting tradition.

Detail from Peter de Hooch, "Woman Peeling Apples," c. 1663.

Another great painting in the Wallace Collection that is hung near The Lace Maker is Peter de Hooch’s Woman Peeling Apples (c. 1663). I use this painting when I lecture on 17th century Dutch art, but I never had seen this painting before in person. The light streaming through the windows is quite lovely, and I like a lot of things about the color and details of this whole painting.

Colossal scarab, perhaps 305-30 BC (possibly earlier)

A colossal scarab! Who knew that such a thing existed?!? This scarab was brought by Lord Elgin (of “Parthenon Marbles” fame) to Britain in the 19th century. I like this scarab for a couple of reasons, including that the scarab was found in Istanbul, although it probably decorated an Egyptian temple. I wonder why the scarab ended up in Istanbul. Scarabs are also interesting to me because of their symbolic associations with rebirth and the sun. Egyptians thought that the scarab was seemingly miraculously hatch out of the dung. In addition, the scarab pushes dung into small balls, much like the god Khepri pushes the sun through the sky.

I took lots of other photos of museums and works of art on this trip, but I think that these are the main “new” (for me, at least) works of art and spaces which will stick out to me the most. Even though we got to visit eight museums, there are still many more things that I wish I could have seen. I already feel the pull go to back, especially since it seems like Millais’s Ophelia is not currently on view at the Tate Britain! I couldn’t find it anywhere. Could that painting have been taken down (or sent off for travel) with the recent rehanging of the Tate’s permanent collection?

What are your favorite works of art and museums in London? Why?