Thursday, February 25th, 2016

Audrey Hepburn and Art

Over the past few weeks I have been involved in a research project involving the actress Audrey Hepburn. In the process, I have been able to catch a glimpse of her artistic preferences and artistic talent, which has been fun. Before this project, my only connection with Audrey Hepburn and art was her role as an art forger’s daughter in How to Steal a Million. Audrey Hepburn was quite private about her personal life, but I have been able to extrapolate a few things that suggest her own preference for art.

Audrey surrounded herself with art and beautiful things like flower gardens, but she also created art. As a child, she also would sketch and draw. These works of art, which were created in the 1940s, seem to serve as a type of escape from the horrors that she experienced while living in Holland during WWII. Some of my favorite scenes include one with a Dutchman and Dutchwoman in clogs who are walking toward the sun, while holding hand with a lion who is wearing a crown (see here) or a compilation of drawings that are inspired by fantasy scenes or nurse rhymes.

As an adult, it seems apparent that Audrey Hepburn and/or her husband Mel Ferrer (married 1954-1968) liked the art of Picasso. (Others have also noted that Audrey Hepburn and Picasso had a similar sense of fashion, since they both wore sailor stripes.) Hepburn attended Picasso: 75th Anniversary Exhibition in 1957, which includes a lovely photograph of her standing next to Picasso’s Self-Portrait with Palette (1906). In addition, the news reported that a drawing by Picasso was stolen from her home in 1962. I couldn’t find any reports as to whether this drawing was ever returned – where did it end up, I wonder? Do any readers know what this drawing looks like?

Audrey also created her own art, too, and I think that some of her personal artistic style might have been indebted to a little to Picasso, but especially Van Gogh. At present, I am only aware of one work of art which has been shown to the public, which is Flower Basket at La Paisible (scroll through images on linked site to see painting).1 This painting was created at her home in Tolochenaz, Switzerland in 1969, when Hepburn was pregnant with her son Luca. The style reminds me a little bit of that of Van Gogh, particularly in the outlines and strokes that are used to create the texture of the wicker basket handle (for comparison, see Van Gogh’s Still Life with Basket and Six Oranges). Hepburn’s buildup of impasto, particularly within the petals of the flowers, also reminds me of Van Gogh. And the green and yellow strokes in the upper corners of Hepburn’s painting remind me of Van Gogh’s paintings of fields, such as Wheat Field at Auvers with White House (1890).

I think it’s likely that she also created the painting behind her in this photograph of Hepburn in her home (although the reduction of the vases and flowers to shapes and colors, as well as the gradients in color saturation actually remind me a little more of Matisse than Van Gogh – see Matisse’s Anemones and Chinese Vase).

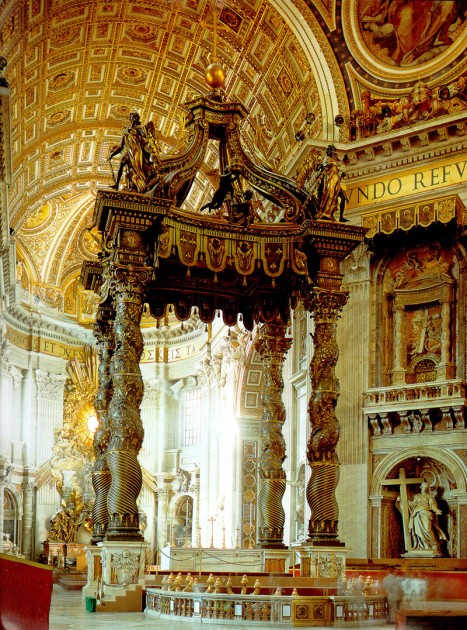

I also think that Audrey may have preferred some older art as well, based on where she lived. When she was married to Andrea Dotti, they lived in the center of Rome in a penthouse that used to be a cardinal’s palace. The space was decorated with soaring ceilings and painted frescoes.1 I haven’t been able to find more specific information on this penthouse (or the frescoes depicted therein), but if anyone knows information on this topic, please share!

Audrey especially loved gardens and the “living art” provided by flowers. Her personal interest in gardens even helped influence her decision to host a documentary series, Gardens of the World (see trailer above). PBS didn’t have the money to pay for Hepburn to have a stylist, but Hepburn insisted that she could do her own wardrobe, hair and makeup for the project. Gardens of the World aired in 1993, shortly after Hepburn’s death.

Hopefully we will continue to learn more about Hepburn’s interest in art (either collecting, creating or viewing art) in the years to come. In 2014, Hepburn’s son, Sean Ferrer, mentioned that several works of art were left behind in Hepburn’s personal effects. It could be that, in the years to come, we will see these works of art put on auction to help raise money for the Audrey Hepburn’s Children Fund.

1 A good reproduction of this painting is available on p. 229 of Sean Ferrer’s book, Audrey Hepburn: An Elegant Spirit. I am hoping to secure permission to post an reproduction of the painting on this site.

2 Donald Spoto, Enchantment: The Life of Audrey Hepburn (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006), p. 271.