Excuse me, Marilyn Stokstad, but I found an error in your art history textbook. Granted, I own a dated version (1999) of Art History (Revised Edition, Volume Two), and I’m hoping that subsequent editions have corrected this error. My copy states the following on p. 647:

“In 1402, a competition was held to determine who would provide bronze relief panels for a new set of doors for the north side of the Florence Baptistery of San Giovanni.” (my emphasis)

This is incorrect. Although the doors resulting from this competition have now ended up on the north side of the baptistery, at the time of the competition these doors were intended for the eastern side of the building.1

The competition to create a set of doors for the baptistery helped revive a project that had been put-aside for several years. When Andrea Pisano had created a set of doors about seventy years before (dated 1330), it was intended at the time that doors would be completed in a similar fashion for the remaining two portals.

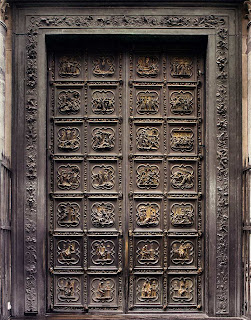

Ghiberti won the competition and a set of doors were completed between 1403-1424 (see above left). At the time of completion, Pisano’s doors were moved from their original location on the east side, in order to accommodate Ghiberti’s new doors.2

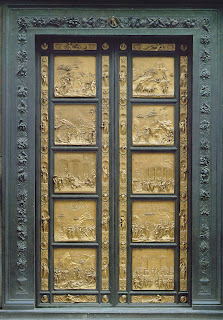

Although Ghiberti’s doors were installed on the eastern side, later they were moved to their current location: the north side of the building. The same year that Ghiberti completed these now-northern doors, he was given a second commission to complete the last set of doors for the baptistery. This second commission resulted in the famous doors which are known as “The Gates of Paradise” (1425-52, see below right), and are currently located on the east side of the building.3

I feel like there’s a lot of confusion regarding Ghiberti’s doors. So much emphasis is placed on “The Gates of Paradise” (and for good reason), that no doubt many people think that these are the doors which immediately resulted from the competition in 1401-02. If you think about it, though, that assumption doesn’t make a lot of sense. Ghiberti’s submission piece for the competition, The Sacrifice of Isaac (1401) was designed within a quatrefoil shape. Likewise, Brunelleschi (Ghiberti’s rival) completed his submission (also called The Sacrifice of Isaac (1401)) for the competition in a quatrefoil. It’s easy to see Ghiberti and Brunelleschi’s logic for using the quatrefoil; they wanted their doors to match the already-existing door by Pisano. After winning the competition, Ghiberti’s used the quatrefoil shape for all the panels in his now-northern doors. Ghiberti only abandoned the quatrefoil shape when he created the doors for his later commission, “The Gates of Paradise.”

It’s easy to look at the competition submissions and see that the north doors resulted from that historic competition. But you need to be able to see the north doors in order to make that association. Many art history textbooks include images of Ghiberti’s and Brunelleschi’s competition panels (see this example in the most recent version of Gardner’s Art Through the Ages), but then don’t include pictures of the north doors. Instead, “The Gates of Paradise” is shown. It’s too confusing to discuss the 1401 competition and then display doors that weren’t directly associated with the competition! If textbook writers could include just an image of the north doors (even a small one), it could help students keep their facts (and doors!) straight.

*7/25: I made a couple of revisions to this post, having found more information about the original location of Andrea Pisano’s doors and the nature of the 1401-02 competition.

1 See Laurie Schneider Adams, Italian Renaissance Art, (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2001), 60. In truth, at this time the Florence baptistery needed two portals to be decorated. The aim of the 1401-02 competition was to begin work on this project. For a little bit more information regarding the nature of the competition, see Manfred Wundram and Gustina Scaglia, “Ghiberti.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T031929pg1 (accessed 26 July 2010).

2 Ibid. Today Pisano’s doors are located on the south side of the baptistery. Manfred Wundram and Gustina Scaglia write that Pisano’s doors were originally moved to the west portal, in order to create room for the doors from Ghiberti’s first commission.

3 The now-northern doors were moved from the east side in 1452, soon after “The Gates of Paradise” were finished.