Monday, November 14th, 2011

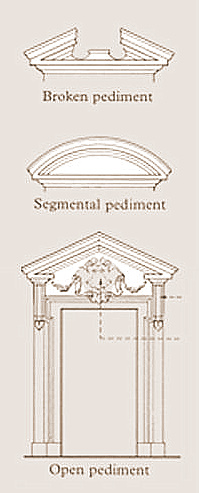

Ancient Greeks and Romans Broke their Pediments

Like other Baroque art historians, I love the broken pediment as an architectural feature. A broken pediment is “broken” at the apex of a triangular pediment. I usually don’t differentiate between the “open” and “broken” pediment when I teach by students about these features, but I know that many architectural historians choose to differentiate between the two. An “open” pediment refers to when the base of the pediment has been removed (or “opened,”). One of my favorite broken pediments from the Baroque period (which actually has been broken, opened, and also shifted backward) is found in the Cornaro Chapel, designed by the artist Bernini (1645-1652).

Both open and broken pediments were popular in Baroque art. Baroque scholars love these kinds of pediments; they serve as good examples of how 17th century architects added a little bit more dynamism and movement into their architectural features (in contrast to the harmony and symmetry that characterized much of the architecture of the Renaissance).1

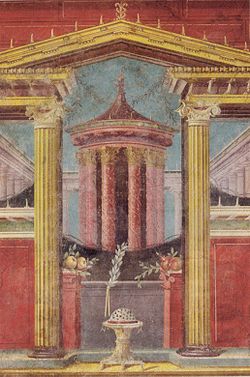

But I think that it’s hard for Baroque scholars to remember sometimes that the idea of segmenting pediments was not developed during the Baroque period. In fact, the broken and/or open pediment existed in ancient Rome and Hellenistic architecture from Alexandria.2 Unfortunately, not many extant examples of architecture survive from Alexandria, so scholars need to look to Roman and/or Nabatean art that copied Alexandrian architecture, such as the Market Gate of Miletus, Treasury at Petra, and Pompeiian wall paintings (all shown below).

I often teach my students about how the Greek Classical period is similar to the art of the Renaissance, and how the Hellenistic period is similar to the art of the Baroque period. The broken pediment in Hellenistic architecture is a further manifestation of this fact. It’s also interesting to see that the Romans picked up on this architectural feature that would probably have been conceived as “distorted” by Greeks who lived during what has been termed the “High Classical” period. In this light, the broken pediment is another manifestation of how Roman architecture was interested in the re-invention of Classical Greek architecture. No wonder they latched onto the Hellenistic invention of the broken pediment.

Here are some examples of broken pediments that appear in ancient Roman art:

Market Gate of Miletus, 2nd century CE. Currently located in the Pergamon Museum (Berlin). Image courtesy of Thorsten Hartmann via Wikipedia.

Facade Al-Khazneh (The Treasury), Petra, Jordan, 2nd century BC -2nd century CE. Image courtesy of Bernard Gagnon on Wikipedia.

Detail of second style wall paintin from cubiculum M of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, Italy, ca. 50-40 BCE

Arch of Tiberius, ca. 26 C.E. (rebuilt around core of earlier monument, ca. 30 B.C.E.), Orange, France

Broken pediment from Temple of Artemis, Jerash, Jordan, c. 150 CE. Image courtesy of Jerzy Strzelecki via Wikipedia.

What are your favorite examples of the broken (or open) pediment in architecture?

1 That being said, there are examples of the broken pediment that exist in Late Renaissance architecture. For example, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger employed broken pediments on the top story of the façade of the Palazzo Farnese (ca. 1530-1546).

2 See Judith McKenzie, “The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, 300 BC to AD 700, Volume 63” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 105. Source available online here. See also Judith McKenzie, “Alexandra and the Origins of Baroque Architecture,” available online here. The latter citation also includes a discussion of how the earliest surviving examples of the segmental pediment (a rounded, semi-circular pediment) are found in Alexandrian architecture.