Tuesday, July 29th, 2008

Apropos

One of the things I love about art history is that art is a visual manifestation of the historical context of its day. I think that a historian can always pinpoint some type of motivation/historical context for the production of a work of art.

Often, it is when I am looking at the historical framework that I experience my “a-ha!” moments of art historical enlightenment. I always get excited when I come up with historical connections on my own. Even if sometimes I see later that another historian already made the connection, I still like to pat myself on the back for at least finding the same correlation.

I thought I would share one connection I made last year that was an “a-ha!” moment, although I’m sure other Baroque historians would scoff at my elementary observation. It has to do with the many depictions of Saint Jerome during the Baroque era. However, I should briefly give a synopsis of the Baroque period so this connection will make sense:

I thought I would share one connection I made last year that was an “a-ha!” moment, although I’m sure other Baroque historians would scoff at my elementary observation. It has to do with the many depictions of Saint Jerome during the Baroque era. However, I should briefly give a synopsis of the Baroque period so this connection will make sense:

The Baroque period of the 17th century was essentially shaped and defined by the Counter-Reformation of the Catholic church, an event which began in the 16th century. Martin Luther’s reformation (begun 1517) and the rise of Protestantism was a threat to the Catholic church; the Counter-Reformation was the Catholic movement to counteract the Reformation. Essentially, the Counter-Reformation was an attempt to bring back the “lost sheep” of Catholic congregations that had fallen-in with the Protestants. Luther and the Protestants found that there were many problems in the Catholic church, such as the sale of indulgences and the veneration of saints. Canons and decrees were issued by the Catholic church to rebuttal claims made by the Protestants.

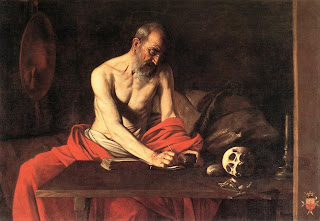

One way that the art of the Baroque period is influenced by the Counter-Reformation is through its dramatic style and composition – plunging diagonals, dramatic lighting and shallow picture planes are supposed to involve the viewer, or make the viewer feel as if he or she is part of the work of art. The art serves as a type of propaganda to help the viewer experience the majesty of the Catholic church first-hand, an experience that would be an aid for conversion.

In addition to style, Baroque art is also influenced by subject matter. The Council of Trent asserts the importance of the veneration of saints, which subsequently led to many depictions of saints in Catholic art at this time. This brings me back to Saint Jerome. I always considered depictions of Saint Jerome to fit into the generalized propaganda for saints and their veneration, but I realized that there really is much more. You see, Saint Jerome is the saint who is responsible for translating the Vulgate from Hebrew and Greek into Latin. The Catholics wanted to justify the use of the canonized Latin text, which was in opposition to the Protestants who felt that the Bible should be translated into the local vernacular. Therefore, not only do depictions of Saint Jerome assert the validity and importance of saints, but these works of art are also a plug for the use of the Latin text within the church!

In addition to style, Baroque art is also influenced by subject matter. The Council of Trent asserts the importance of the veneration of saints, which subsequently led to many depictions of saints in Catholic art at this time. This brings me back to Saint Jerome. I always considered depictions of Saint Jerome to fit into the generalized propaganda for saints and their veneration, but I realized that there really is much more. You see, Saint Jerome is the saint who is responsible for translating the Vulgate from Hebrew and Greek into Latin. The Catholics wanted to justify the use of the canonized Latin text, which was in opposition to the Protestants who felt that the Bible should be translated into the local vernacular. Therefore, not only do depictions of Saint Jerome assert the validity and importance of saints, but these works of art are also a plug for the use of the Latin text within the church!

There are many depictions of Saint Jerome from this period, and now I can see why. It’s dual propagandistic in purpose – the Catholics could get two propagandistic statements out of one artistic commission. Isn’t it absolutely fascinating how perfectly these depictions reveal the historical context and sentiment of their day? *Sigh* – it’s so great. I wish that museum labels could be long enough to explain all of these historical intricacies – they make works of art infinitely more interesting.

So, keep your eyes out for Baroque depictions of Saint Jerome. You can’t miss him – he’s often working on his Vulgate translation and is typically identified by a skull (man is born to die but the Word is eternal). The paintings included in this post are both by Caravaggio. The first one is from about 1607-08, and the second one was made slightly earlier, about 1605.