Tuesday, June 4th, 2013

“She’s Got the Look!”: Portraits of Prospective Royal Brides

Hans Holbein, Portrait of Anne of Cleves c. 1539. Parchment mounted on canvas, 65 x 48 cm Musée du Louvre, Paris

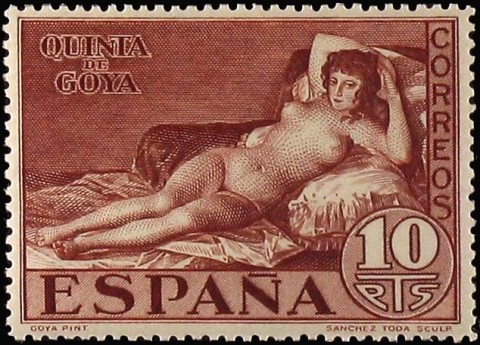

I’ve chucked a few times today about the post “Anne of Cleves Gables,” which is especially if amusing if you are familiar with both the Anne of Green Gables series and the story behind the portrait by Holbein (above). I guess if Henry VIII hypothetically could have known the popular song “She’s Got the Look!” by the group Roxette, he might have sung the lyrics when looking at Holbein’s portrait of Anne, but probably would not have thought of that music when he actually met Anne in person.

Holbein was sent to Düren in 1539 to create a portrait of the widow Anne of Cleves for Henry VIII; the king wanted to see whether he would like to take Anne as a bride. There is no doubt that Holbein must have felt a lot of pressure. Henry VIII was in his late forties and already had been married three times before this point. Henry VIII was very displeased upon seeing Anne in person (finding her to be a “fat Flanders mare”), which seems to suggest to me that Holbein created Anne to be more flattering than her actual appearance. There are no records of Henry VIII’s actual reaction to Holbein’s portrait, however. Interestingly, we know that Henry VIII was quite smitten with a portrait that Holbein previously created of Christina of Denmark, who also was considered by Henry VIII as a prospective bride (see below).

Hans Holbein the Younger, "Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan," 1538, oil on oak, 179.1 x 82.6 cm. National Gallery of Art, London

It is recorded that Henry VIII had musicians play all day long when he saw this portrait of Christina, so he could feast all day on music (the food of love). However, Christina wasn’t selected as a bride. All in all, these portraits may have been helpful for Henry, but not the ultimate decision-making tool for marriage. Historian David Starkey claims that influential courtiers convinced Henry VIII to marry Anne instead of Christina.

Several other Renaissance and Baroque artists were commissioned to paint portraits of prospective brides or husbands for rulers. This idea of painting the likeness of a prospective spouse really seems to be a new phenomenon for the Renaissance, which makes sense due to the rise of both portraiture and naturalism in Renaissance art. I thought it would be fun to create a list with information about prospective bride and/or betrothal portraits, so I started a list here:

- Charles VI of France (c. 1380-1422) is recorded to have sent his painter to three different royal courts to create portraits of prospective brides.

- Jan Van Eyck, Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, 1428 (now lost, although a copy is thought to exist). This was painted as a betrothal portrait after the marriage agreement had already taken place (to function as a visual assertion of Isabella’s identity for when she arrived in Burgandy).

- Catherine de’Medici expressed disapproval in the portrait of Elizabeth I that was created for her son Charles IX. Luckily, Catherine blamed the portrait on the portraitist, not on Elizabeth herself. Consequently, on 3 July 1571, Catherine wrote to Monsieur de la Mothe-Fénelon, ambassador in London, requested a new portrait be created: “I pray you do me the pleasure that I may soon have a painting of the queen of England of small volume, in great [de la grandeur], and that it be well portrayed and done in the same fashion as the one sent be by the earl of Leicester, and ask, as I already have one in full face, it would be better to have her turning to the right.”

- Nicholas Hilliard (also spelled “Nicholas Belliart”) was sent by Catherine de’Medici to Sweden and Denmark in 1574 to paint portraits of prospective wives for Catherine’s son, Henry III.

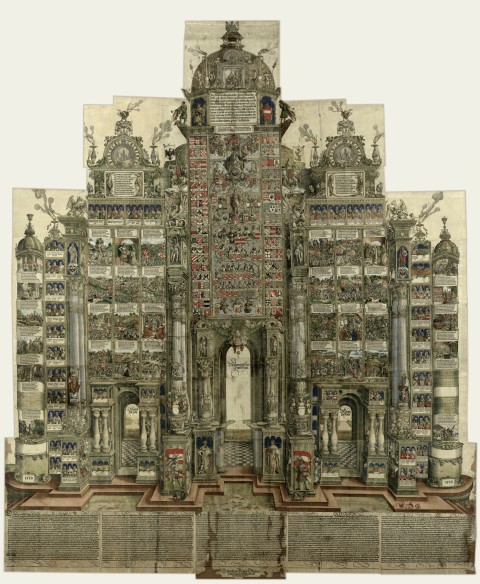

Rubens, Henry IV Receiving the Portrait of Marie de'Medici, 1621-1625. Oil on canvas, approx. 13' x 9'8" (3.94 x 2.95m), Louvre

- Marie de’Medici was so proud of her “prospective bride portrait” that was sent to Henry IV that later, after she and Henry were married, she commissioned Rubens to depict Henry falling in love upon seeing her portrait for the first time!

Anything else we could add to this list? I couldn’t pinpoint images for several of the portraits mentioned above, so please comment and leave a link if you know of their existence online. Also, please feel free to share further examples and thoughts on this topic in the comments below.

And I go: la la la la la / She’s got the look!