Tuesday, March 17th, 2009

Juxtaposition of Images

Mieke Bal’s book Looking In: The Art Of Viewing has forever changed the way that I look at exhibitions in art museums and galleries. In her chapter “On Grouping,” Bal discusses how the juxtaposition of different images on a museum wall can create meanings and connotations which never would have existed otherwise. She discusses a grouping of three paintings in a Berlin museum: Amor Vincit Omnia (Caravaggio), Doubting Thomas (Caravaggio, shown above) and also Heavenly Amor Defeats Earthly Love (Baglione). Specifically, she argues that the placement of Doubting Thomas between these two images of nudes creates a new dynamic within the first painting. For Bal, she feels like “Jesus’ barely visible leg at the lower left becomes slightly coquettish” when placed alongside Caravaggio’s nude Amor (whose sprawled legs cover a good portion of its canvas).1 If you’re interested, you can read parts of Bal’s argument and see a grouping of the three images online.

Mieke Bal’s book Looking In: The Art Of Viewing has forever changed the way that I look at exhibitions in art museums and galleries. In her chapter “On Grouping,” Bal discusses how the juxtaposition of different images on a museum wall can create meanings and connotations which never would have existed otherwise. She discusses a grouping of three paintings in a Berlin museum: Amor Vincit Omnia (Caravaggio), Doubting Thomas (Caravaggio, shown above) and also Heavenly Amor Defeats Earthly Love (Baglione). Specifically, she argues that the placement of Doubting Thomas between these two images of nudes creates a new dynamic within the first painting. For Bal, she feels like “Jesus’ barely visible leg at the lower left becomes slightly coquettish” when placed alongside Caravaggio’s nude Amor (whose sprawled legs cover a good portion of its canvas).1 If you’re interested, you can read parts of Bal’s argument and see a grouping of the three images online.

Since reading this article a few years ago, I am constantly looking for new meanings and connotations which come about because of the juxtaposition of images in a museum. A few years ago I helped hang an exhibition which featured work by the artist Sean Diediker. Due to the size of the paintings and the space of the museum, it ended up that a large painting of a female nude was placed to the left of a painting of Joseph Smith (the Mormon prophet) receiving a vision. Joseph Smith was kneeling down in semi-profile, looking at a vision that was placed to the left of the picture frame. If the picture frames between the nude and Smith were invisible, then the boy prophet would have been looking right at the nude woman. All of the sudden, the look of surprise and awe on Joseph Smith’s face began to look a little more embarrassed, as if he wasn’t supposed to be staring at a nude female!

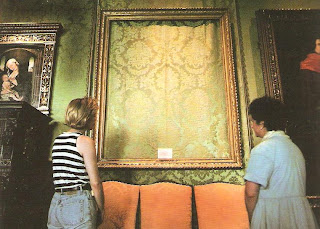

As Bal points out in her book, every viewer brings their own personal experiences (“cultural baggage”) and past to a work of art. Therefore, we all have our own personal reaction to what kind of dialogue and connotations are created by a work of art. The writer of this article reacted to a past installation at the Whitney Museum (shown below), saying that “the juxtaposition of Urs Fischer’s Intelligence of Flowers (holes in the wall) and Untitled (hanging shapes) with Rudolf Stingel’s black & white photorealistic self-portrait creates an impression of crushing despondency in the face of a wrecked world.”

I agree that such a reaction to this exhibition of art is possible. Personally though, having just seen a recent episodes of LOST that involve swinging pendulums and abandoned Dharma Initiative stations, I can’t help but think of anything else when I look at these hanging shapes, circles, and gaping holes.

Have you ever found interesting connotations or dialogue that was created by the juxtaposition of artwork? What kind of personal “cultural baggage” has affected your reaction to a work of art?

1 Mieke Bal, Looking In: The Art Of Viewing (New York: Routledge, 2000), 184.