Thursday, September 12th, 2013

Ottonian “Baroque” Elements

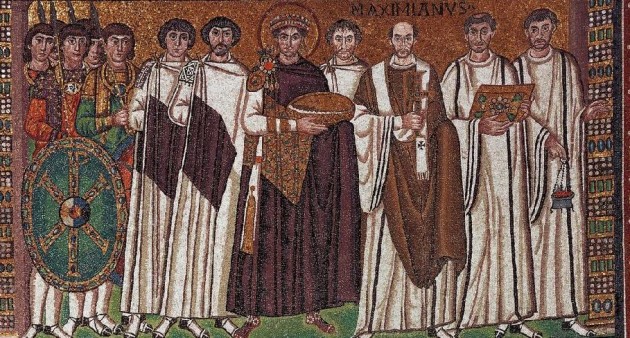

"Christ and Apostles on the Sea of Galilee" from the Hitda Codex, c. 1025-50 CE. Ms. 1640, folio 117

Over the past week I have been transcribing my handwritten art history notes from my undergraduate years into digital format. I’ve been working on the notes from my class on medieval art, and I’ve been struck that my past professor casually referred to some Ottonian works of art as “baroque” in style. Although the Ottonian period is often referred to as a “renaissance” in terms of a rebirth of artistic production (with classical influence feeding into the Ottonian style from both the Carolingians and Rome itself), I can see what my professor is saying about a few instances in which baroque elements can be found in Ottonian art.

For example, the bow and stern of the ship in “Christ and the Apostles on the Seat of Galilee” from the Hitda Codex (shown above) seem to strain against the border of the manuscript itself, as if pushing forward into the actual space of the viewer.1 The sweeping curves of the ship remind me of the undulating, Borrominesque curves found in 17th century architecture. And the dramatically-windblown sail reminds me of the grandiose “cloth of honor” that is found in many Baroque paintings, such as the Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin from 1606.

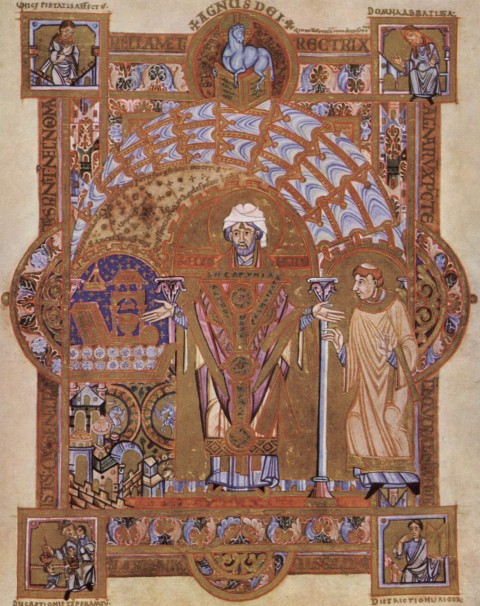

My professor also felt like the Ottonian School of Regensburg was the “baroque phase” of Ottonian illumination, largely because the works of art are so visually complex. The Uta Codex is from Regensburg and includes several masterpiece manuscripts, such as “St. Erhard Celebrating the Mass.”2 Visual complexity is typified in the dynamic, decorative canopy which sweeps over the head of St. Erhard. The manuscript is also filled with excessive decoration and detail. Semi-circles seem to bulge out of the sides of the rectangular border of the frame, which adds a dynamic element that arguably could be called baroque.

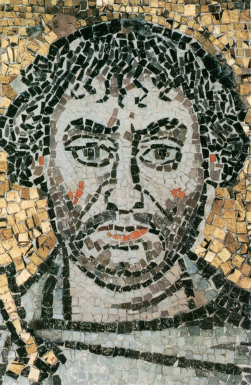

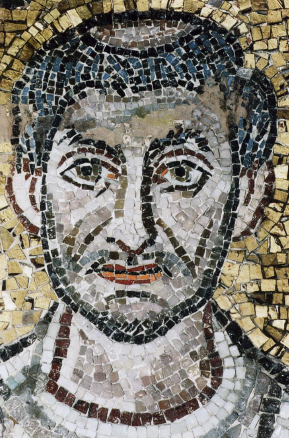

Detail of Creator introducing Adam and Eve, from the Hildesheim Doors, 1015. Photo via petrus.agricola via Flickr

While thinking about such baroque elements in Ottonian art, I also was reminded of an article by Harvey Stahl, “Eve’s Reach: A Note on the Dramatic Elements in the Hildesheim Doors” (.PDF available online). Stahl discusses how there are dramatic elements and moments of tension in the doors, which help to encourage the viewer to follow the narrative. I think that this element of drama has some parallels with the aesthetic and subject matter of the Baroque period. One such dramatic element found in the panel in which Adam and Eve are introduced. Here, Adam and Eve reach for each other, but are depicted as almost touching. Stahl explores this idea of drama and tension, finding that the doors were influenced by the plays written by Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim about a half-century before Bishop Bernward commissioned these doors.3

Although I do not claim that these Ottonian elements had a direct impact on Baroque artists, I do like to think that this might be another slight example of the cyclical nature of art. Perhaps, in some ways, the classical style of the Carolingians led into a few Ottonian dramatic elements and visual distortions that could be seen as departures from the “classical calm,” similar to how the Renaissance style of the 15th and 16th centuries led into the Baroque style of the 17th century.

1 For more images from the Hitda Codex, scroll to the bottom of this website: http://www.oberlin.edu/images/Art310/Art310f.html

2 For more information on this manuscript, see http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth212/liturgical_objects/liturgical_objects2.html and http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/catholic_historical_review/v088/88.4mayr-harting.html. I especially like that Abbess Uta, the original owner of the manuscript, is depicted in the upper-right corner.

3 Harvey Stahl, “A Note on the Dramatic Elements in the HIldesheim Doors” from Reading Medieval Images by Elizabeth Sears and Thelma K. Thomas, eds. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2002), p. 163, 168, 169.