Friday, August 5th, 2011

Underneath the Colosseum

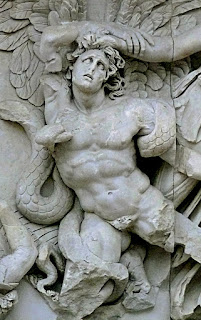

I’ve always really liked the Colosseum (70-80 CE, shown on left) and its history: Vespasian! Nero the Loser! Gladiators! The bastardization of Greek architectural orders! But even apart from art history, I personally have a soft spot for the Colosseum because of my own experience in Rome: several years ago I got to see Paul McCartney play a (free) concert outside the arena. It was awesome to see the Colosseum “rocking out” in florescent lights, serving as a backdrop to Beatles music.

Since I am featuring a giveaway for two subscriptions to Smithsonian magazine this week, I thought it would be fitting to write a post inspired by a Smithsonian article. I immediately turned to an article about the Colosseum in a Smithsonian issue from earlier this year (“Secrets of the Colosseum” by Tom Mueller, January 2011). This article contains some interesting, lesser-known facts about the Colosseum. For example, did you know that during the Renaissance Pope Sixtus V tried to turn the Colosseum ruins into a wool factory? Luckily, that project was abandoned after Sixtus V died in 1590. Phew!

The bulk of the Smithsonian article focuses on the hypogeum, the area beneath the arena floor of the Colosseum (see below). This area provided a network of service rooms and tunnels for performers, athletes, animals, and equipment. Currently, there has been a lot of hype created about the hypogeum (ha ha!). This area and the third floor of the Colosseum were just recently opened to the public last fall, following a $1.4 million restoration project. From what I understand, the hypogeum will probably be open through October of this year.

I’ve always thought that the hypogeum was particularly interesting, especially since I once heard that the hypogeum has its own unique ecological niche. For centuries, plants have rooted among these underground ruins. These plants are located quite far beneath the regular ground level and probably experience a unique range of external temperatures, sunlight, and rainfall. With such unusual conditions, one can suspect why botanists have been interested in these plants for such a long time. “As early as 1643, naturalists began compiling detailed catalogs of the flora, listing 337 different species.”1 Multiple surveys have taken place since then; in 2003 it was recorded that the combined lists contain 683 species.

I especially liked how the Smithsonian article discussed how the hypogeum allowed Colosseum spectacles to maintain an element of surprise and suspense. For example, animals that were held in the hypogeum would enter the arena on a wooden ramp at the top of a lift. “Eyewitnesses describe how animals appeared suddenly from below, as if by magic, sometimes apparently launched high into the air.”2 The hunter in the arena would never be sure of where the next animal(s) would appear.

I can’t help but think of Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games books after reading more about the surprise tactics used in Colosseum events. Although I had made connections between the Hunger Games and the Colosseum before (in both instances contestants are supposed to fight to the death), I hadn’t considered more parallels. The arenas for the Hunger Games were designed to continually introduce new surprises to the contestants. I even recall at least one instance (I think it was in Catching Fire) in which Katniss is lifted into the arena in a glass cylinder, suggesting that she was held in an underground space similar to the hypogeum.

Anyhow, I wonder how much Collins researched the Colosseum while writing her books. Has anyone else read The Hunger Games series? Can you think of more parallels between the Colosseum and the Hunger Games? What are your favorite things about the Colosseum?