Tuesday, November 8th, 2016

Marilyn Monroe and Art

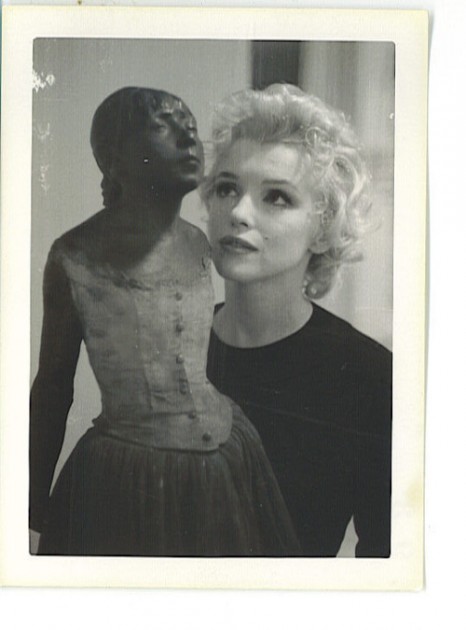

Marilyn Monroe looking at a statue of Edgar Degas’ “Little Dancer of Fourteen Years.” Photo taken at William Goetz’s house, 1956

For those who follow my blog, you may have noticed that I have been researching stars and celebrities of the mid-20th century over the past several months. Out of all of the people that I have studied thus far, Marilyn Monroe stands out as one of the people who is most interested in the Western artistic tradition. I was surprised to make this connection, because it never occurred to me that Marilyn would be interested in visual art.

As an art historian and educator, I especially enjoyed reading about Marilyn’s experience in taking an art appreciation class (one biographer writes that Marilyn’s class was at UCLA, but her autobiography says that the course was at the University of Southern California). In her autobiography, Marilyn shared her opinion of her art appreciation teacher and the course:

She was one of the most exciting human beings I had ever met. She talked about the Renaissance and made it sound ten times more important than the Studio’s biggest epic. I drank in everything she said. I met Michelangelo and Raphael and Tintoretto. There was a new genius to hear about every day.

At night I lay in bed at night wishing I could have lived in the Renaissance. Of course I would be dead now. But it seemed almost worth it.1

I was so touched to learn about the great impact that this teacher had on Marilyn Monroe. I can only hope to be as inspiring of an art instructor! After the course, Marilyn continued to learn about art, and I was especially amused at an anecdote about how she read a disappointing book about Goya (which, fortunately, didn’t hinder her enthusiasm for Goya’s art).

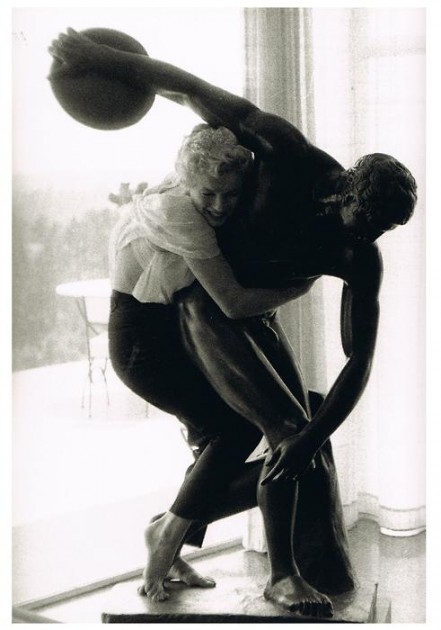

Marilyn Monroe posing with hairdresser Sidney Guilaroff’s statue of the Discobolus (“Discus Thrower”). Photo by Milton Greene, 1956

To further her knowledge and experiences with art, Marilyn attended art exhibitions. She particularly liked the sculptor Rodin, and attended the 1955 exhibition of Rodin’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was recorded that she was particularly drawn to Pygmalion and Galatea and The Hand of God.2

In fact, Marilyn liked The Hand of God so much that she bought a bronze sculpture of in 1962 (similar to the one shown above), for more than one thousand dollars. This was the last year of Marilyn’s life, and her emotional well-being was already unraveling. She promptly brought the statue to her psychiatrist and engaged in a bizarre and troubling conversation in which she kept asking the doctor to tell her what he thought the work of art meant.3 (Marilyn was particularly confused by how the multiple bodies were interacting with each other; it is easier to see them online by looking at a 3-D model of the sculpture.) I think it’s very interesting that Marilyn felt an affinity with this particular sculpture near the end of her difficult life: the Rodin Museum says that this hand was used as a study for Rodin’s “The Burghers of Calais,” in which the hand gestures express farewell and despair.

Marilyn collected other art, too. I’m particularly intrigued that in July 1955, she purchased a bust of Queen Nefertiti for her Waldorf-Astoria apartment in New York (although I can’t find information as to whether this was an authentic bust or a copy of the famous bust located in the Neues Museum in Berlin). As a well-established symbol of feminine beauty, it is intriguing to me that she would be drawn to an idealized image of Egyptian beauty.

Does anyone know what became of Marilyn’s art collection? Was it dispersed along with other parts of her estate?

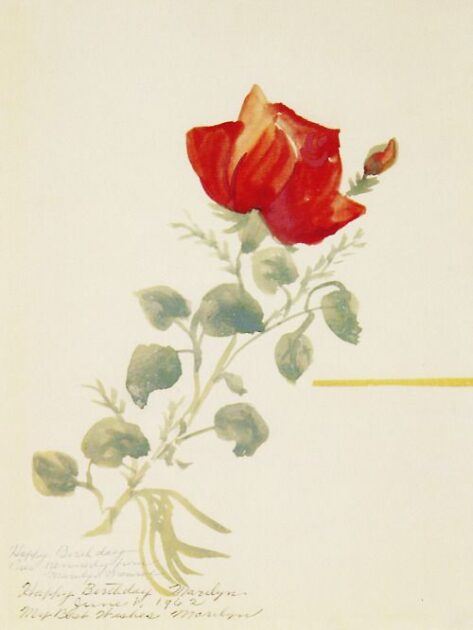

UPDATE 4/24/22: Someone on Twitter posted this picture of a rose that was painted by Marilyn Monroe in 1962. It is fun to know that she was interested in making art on her own:

1 Marilyn Monroe and Ben Hecht, My Story (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield) p. 139-140. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=VbOIqnTRumIC&lpg=PP1&dq=marilyn%20monroe%20my%20story&pg=PA139#v=onepage&q&f=false

2 Anthony Summers, Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe, 389. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=g8gJZltbC2MC&lpg=PP1&dq=goddess%20marilyn%20monroe&pg=PT242#v=onepage&q&f=false

3 Ibid. 200-01.