Tuesday, October 5th, 2010

"Masculine" vs. "Feminine" vs. "Androgynous"

This quarter I have been peppering my lectures with some discussion about women in the visual arts, following some of the ideas that Christine Havice presented in Women’s Studies Quarterly. 1 Although art historical practice and publications have changed since Havice published her article in 1987, I think that many of her suggestions are still appropriate in the classroom today.

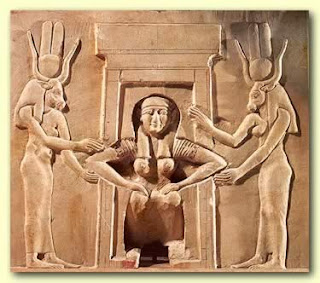

Recently I’ve been talking with my students about Akhenaten and the Amarna period in Egyptian art (on the left is the colossal figure of Akhenaten, c. 1353-1336 BC). This topic easily segued into a discussion (prompted by Havice) about the problematic nature of the labeling an artistic style or work of art as “masculine” and “feminine.” We discussed how our 21st century idea (i.e. construct) of “masculine” and “feminine” differs greatly (or likely didn’t even exist) in prehistoric and ancient times, and by using those labels we are superimposing our cultural ideology on a work of art. All in all, using such adjectives in art historical discussions implies that a similar “masculine” or “feminine” construct existed at the time the art was created.

Sigh. And such is the challenge for art historians. I think it is often difficult to find correct (i.e. objective) adjectives and phrases to describe works of art, because we always interpret works of our through our own cultural lenses. I’d like to think that Michael Ann Holly would agree with me on this subject, since she has much lamented the melancholic separation between historians and the objects of their scholarly discussion.

So, what do we do? Search for different adjectives? Continue to describe works of art in the best way that we know how, yet recognizing the surrounding culture from whence our biases spring? We obviously can’t ditch adjectives altogether; the discipline of art history revolves around the limited translation of images to words.

I don’t know the answers to solve such conundrums regarding adjectives, but I have formed one opinion about adjectives for the Amarna style. I think it is just as problematic to try and neutralize ground between the “masculine” and “feminine” terms by saying that Akenaten’s colossal statue “suggest[s] androgyny” (sorry, Marilyn Stokstad).2 Do we know if Akhenaten was trying to appear androgynous in his art? No! Even without using the “masculine” or “feminine” label, Stokstad is trying to define this statue on sexual grounds, in this case suggesting the lack or combination of sexual characteristics as a definition. (Besides, do we even know if the concept of androgyny existed in ancient Egypt?) I think it would have been more appropriate for Stokstad to say that the sculpture may suggest androgyny to the modern viewer.

1 Christine Havice, “Teaching about Women in the Visual Arts: The Art History Survey Transfigured,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 15, no. 1/2 (Spring-Summer 1987): 17-20.

2 Marilyn Stokstad and Michael W. Cothren, Art History, 4th edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2011), 71.