Thursday, December 10th, 2009

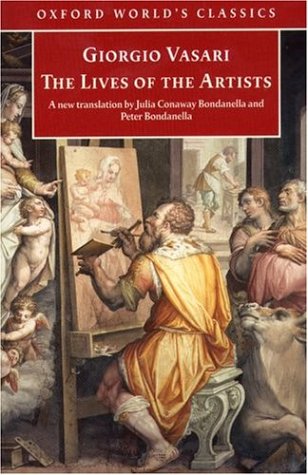

Book Review: Vasari’s "The Lives of the Artists"

Well faithful readers, I’m sure that you’re tired of hearing about Vasari in my posts. I don’t blame you. I’ve been writing Vasari-inspired posts for the past several weeks, as I’ve slowly worked my way through the Lives of the Artists text. The funny thing is, I never intended on reading the whole book this fall. I checked out Lives so that I could verify a couple of quotes, but then I just kept reading. And reading. And reading. And now, 500+ pages later, I’ve finally finished! So, this review will probably be my last Vasari-centric post, at least for a while. Here are my final thoughts on Vasari’s Lives:

Well faithful readers, I’m sure that you’re tired of hearing about Vasari in my posts. I don’t blame you. I’ve been writing Vasari-inspired posts for the past several weeks, as I’ve slowly worked my way through the Lives of the Artists text. The funny thing is, I never intended on reading the whole book this fall. I checked out Lives so that I could verify a couple of quotes, but then I just kept reading. And reading. And reading. And now, 500+ pages later, I’ve finally finished! So, this review will probably be my last Vasari-centric post, at least for a while. Here are my final thoughts on Vasari’s Lives:

– This book is simultaneously boring and fascinating. It’s difficult to read Vasari’s lengthy passages which describe works of art, especially since there were no reproductions available in my text. (This website, however, promises to display illustrations with each biography, although I don’t know if all extant reproductions will be provided for every description in the text.) However, many of Vasari’s anecdotes and short stories are really fascinating. I especailly found the story of Brunelleschi and Ghiberti’s rivalry to be quite riveting.

– Vasari’s hyperbolic writing style is a little silly. He is over-the-top in his praise for the majority of artists in the book. Likewise, much of art in the book is described as the most beautiful thing in the world – those descriptions become old after a few paragraphs. Vasari also opens many chapters with generalized, broad statements about life, happiness, or art (a type of “Happy is the man who…” statement), and that also gets a little annoying.

– I can see why Vasari is sometimes called “The Father of Art History.” His methodology of verifying multiple sources for information helped set a precedent for the discipline. He also offers critiques for works of art, and it’s easy to see how he helped to set the standard for art criticism. Even though his writing is prolix and dull at times, it’s quite interesting to see his methodology and ideological influences.

– I would recommend this book to a serious art historian. I think anyone with a mild interest in art would get bored quite easily: the interesting anecdotes and stories are embedded deep within Vasari’s text. If you want to know more interesting stories without reading the book, just let me know. I took notes!

* I am counting this book as part of Heidenkind’s Art History Challenge.