“…have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” – William Morris

Today is somewhat of an exciting day at my house. We moved into our place a few years ago, and over the past several months we have been accruing reproductions of our favorite pieces of art to display around the house. Today, the final framed print arrived! Although I’m sure that we will buy some more pieces over time (and hopefully actual works of art one day, not just reproductions), I think we are set in our arrangement for the time being.

I wanted to jot down some things about the pieces that we decided to purchase for our home over the past few years, so I can remember a little bit about each work. (I also remember enjoying when my friend Hasan wrote a similar post last fall, which ended up being one of the last posts on his site.) Keep in mind that my husband and I have a collective aesthetic that is very narrow. I love older historical pieces, while my husband prefers modern and contemporary art. We usually are able to find a middle ground in art from the nineteenth century as a compromise.

Roy Lichtenstein, Rouen Cathedral promo set, January-July 1969

We have a small set of prints that were made to promote Lichtenstein’s “Rouen Cathedral” series. Of course, Lichtenstein’s printed series was made in homage to Monet’s famous paintings. The painted series by Lichtenstein is made out of ben-day dots, and the paintings are blown up to a large scale so that the dots are extremely visible.

I’m not sure if the complete series by Lichtenstein was finished. When we bought this set, we also received a flyer (printed in April 1969) which mentioned that the actual projected series had fourteen paintings by Lichtenstein, although it remained unfinished at the time the flyer was written. (If anyone knows more information on this series, please share!) At present, I am aware of two sets from this series: Rouen Cathedral, Set V (1969) and Rouen Cathedral (Seen at Five Different Times of Day), Set III (1968-69).

Odilon Redon, “A Vase of Blue Flowers,” c. 1905-1908. Pastel on paper, private collection.

My husband gave this Redon print to me for Christmas a few years ago, as the first work of art to hang in our new place. Unlike the bizarre and fantastic imagery which Redon created during much of his career, Redon created a lot of pastels of flowers during the last fifteen years of his life. I like a lot of his floral still lifes, but this one works especially well within our living space.

Gustave Caillebotte, “On the Pont de l’Europe,” 1876. Oil on canvas. Kimbell Art Museum.

We got a print of On the Pont de l’Europe (1876-1877) by Caillebotte after seeing the original during a trip to the Kimbell Art Museum in December 2011. I really like the bluish-grey color palette and asymmetrical composition of this piece. In fact, I think I like this painting better than Caillebotte’s other treatment of the same bridge (see Le Pont de l’Europe from 1876). One of the things that I think is interesting about my print is that the scene overlooks the Saint-Lazare train station, a place which served as subject matter for many of Monet’s paintings. More information about this painting can be found HERE.

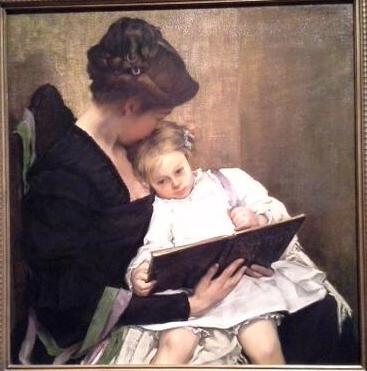

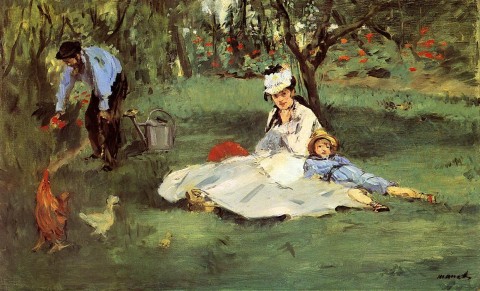

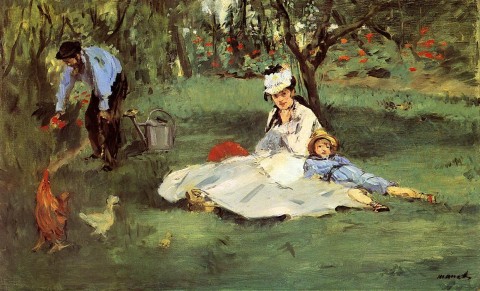

Manet, “The Monet Family at Argenteuil,” 1874

I got a print of “The Monet Family at Argenteuil” around the time that I wrote a post which included this painting. In that post, I mentioned that Manet and Renoir worked side by side in 1874 to paint the Monet family members. I think Manet’s painting is so much better; Renoir’s Madame Monet and Her Son (also called Camille Monet and Her Son Jean in the Garden at Argenteuil) is simply atrocious in comparison to Manet’s strong composition and use of color.

Arthur Melville, “The Blue Night – Venice,” 1897. Watercolor and gouache on board, Tate Museum.

After visiting London last summer, we got a copy of Melville’s The Blue Night – Venice (1897). I saw this painting while visiting the Tate with my cousin; my husband was visiting Cambridge that morning and missed going to the Tate with us. I took this photograph to show my husband, and we both liked the painting so much that we wanted to buy a print as a momento.

This painting captures some key places in Venice: the Campanile, the Doge’s Palace, and Saint Mark’s Cathedral. One of the reasons that I am drawn to this painting is due to the striking color and hazy definition of forms. I think that the striking properties of this painting are due to the fact that Melville championed a new watercolor technique. The TATE website explains: “He saturated the paper with Chinese white paint and used sponges to create a velvet-like texture. Before applying the paint, he tried out ideas on pieces of glass held over the painting. Colour, such as the blue used here, drew attention not just to the subject of the work, but to the medium itself.”

Gustave Klimt, “Attersee,” 1901. Oil on canvas, approx. 2.5′ x 2.5′ (80.2 cm x 80.2 cm). Leopold Museum, Vienna

We have a very small print of Klimt’s “Attersee” (1901), which my husband got after a trip to Vienna last fall. This painting is of a Lake Attersee, which Klimt visited repeatedly as a summer retreat. Klimt would travel to Attersee to spend summers with his lifelong companion, Emilie Flöge, and her family. He also painted other works of art during this same retreat in 1901, including Tannenwald I and Tannenwald II. More information about this painting is found HERE.

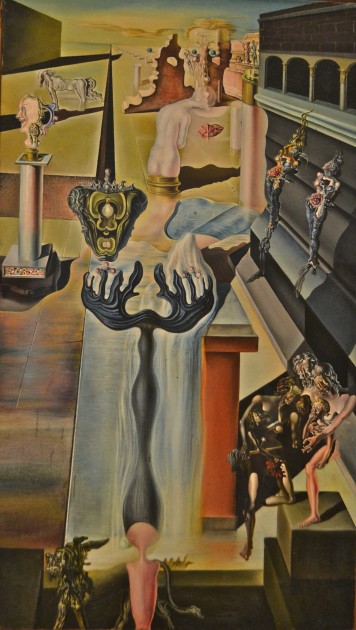

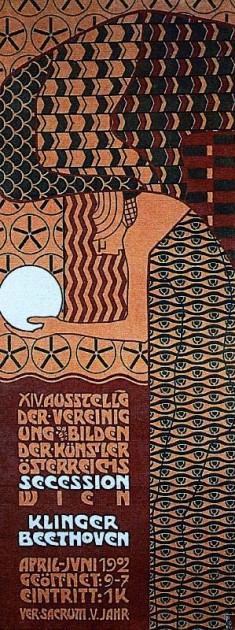

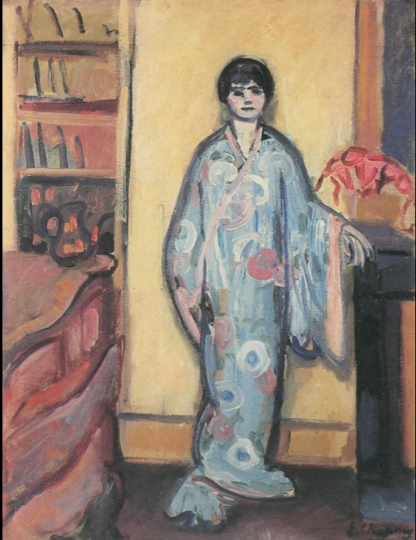

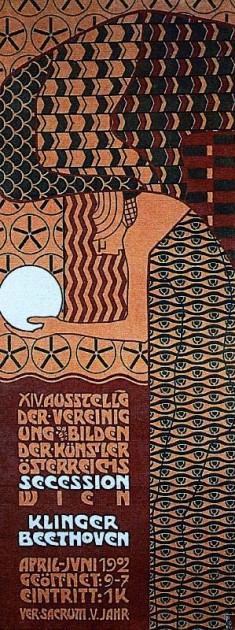

Alfred Roller, Poster For the 14th Exhibition of Vienna Secession, c.1902

We also got this poster print after my husband returned from his trip to Austria. Some view this poster as an anticipation of Cubism and Art Deco.1 I am still trying to find more information about this poster and its imagery, but I did find out that this poster was included in an exhibition at Harvard, which highlighted a “subversive triumvirate” of the feminine, the decorative, and the abstract.

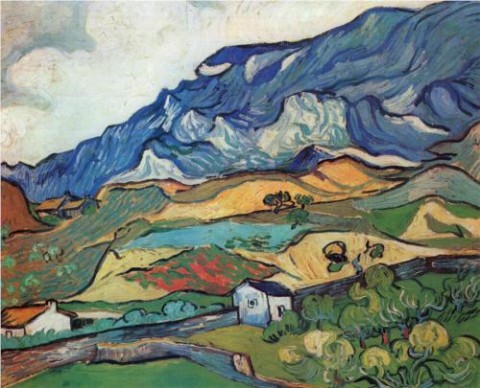

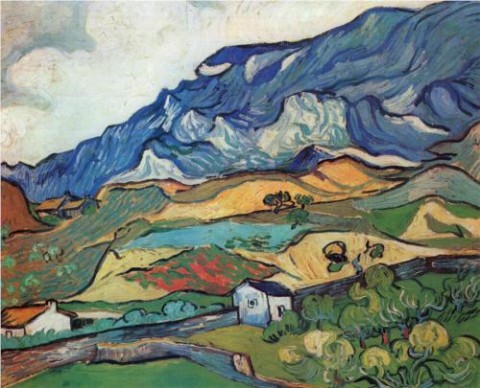

Van Gogh, “Les Alpilles Mountain Landscape Near Saint-Rémy,” 1889. Oil on canvas, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, Netherlands

I have wanted to have a some type of Van Gogh print in my home for some time. I really love his Almond Blossom (1890) painting, but I don’t have the right wall colors in my home to complement the blue background. My husband and I liked this print not only for its colors, but also because we weren’t familiar with this painting before stumbling upon it online. This particular painting was done during the period when Van Gogh lived in Saint-Rémy (from May 1889 until May 1890); Van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself into the Saint-Paul asylum located in this area.

Willem van Aelst, “Floral Still Life with a Pocketwatch” (“Still Life with Poppies and Roses”), 1663. Oil on canvas, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The print that we received today is a copy of this painting by Willem van Aelst. I’m afraid that my print does not look nearly as luminous as the actual painting itself, but I’m still happy. I’ve liked the idea of having a Dutch still life in my home for some time, but my husband and I could not find a print that we both liked. However, my husband saw this painting in the Rijksmuseum during a recent trip to Amsterdam, and I readily agreed that it would look nice in our home. I love all of the little details in this painting, from the butterflies and bugs to the small key that is connected to the ribbon.

Willem van Aelst is perhaps somewhat a lesser known still life painter today, although he achieved a lot of fame and prestige during his lifetime. Today, I think that his pupil, Rachel Ruysch, is perhaps a little better known. According to a biography on van Aelst, he was one of the first painters to create asymmetrical still life compositions during his day. (It’s no wonder that my husband, with his modern eye, would be drawn to this composition!)

Bowen family, “Fake Albers,” 2012

And, just for fun, I’ll end this post with some fake “Homage to the Square” prints that my family created a few years ago. My husband really loves the work of Josef Albers, but we couldn’t find prints in his square series which fit with the colors we wanted to highlight in our home. So, we designed our own! My son and I each picked out one of the color schemes, and my husband chose the final two. He designed the prints based off of actual Albers prints.