Wednesday, January 7th, 2009

Before Christmas, I worked on a project which involved scanning and transcribing the letters of a WWII soldier (Grandpa B) to his wife (Grandma B). It was a really fun project and gave me a nice break from unpacking and remodeling. J helped me transcribe some letters, including one that discussed Grandpa B’s reaction to Roosevelt’s sudden death. Both J and I knew that Roosevelt had died suddenly, but neither of us knew the details.

Before Christmas, I worked on a project which involved scanning and transcribing the letters of a WWII soldier (Grandpa B) to his wife (Grandma B). It was a really fun project and gave me a nice break from unpacking and remodeling. J helped me transcribe some letters, including one that discussed Grandpa B’s reaction to Roosevelt’s sudden death. Both J and I knew that Roosevelt had died suddenly, but neither of us knew the details.

After looking it up, we discovered that Roosevelt collapsed on April 12, 1945 while he was sitting for a portrait with the painter Elizabeth Shoumatoff. He died that same day from a cerebral hemorrhage. I don’t think there are any other important historical figures who have collapsed (and subsequently died) while sitting for a portrait. (Can anyone prove me wrong?)

This is a reproduction of Shoumatoff’s unfinished portrait of the president. The original portrait hangs in “The Little White House” museum in Georgia.

As has been commented elsewhere, I think that that this unfinished portrait is a visual representation of FDR’s unfinished presidential term. Roosevelt never got to see the defeat of Nazi Germany (V-E Day), and although he ordered the construction of the atomic bomb, he never was faced with the decision of dropping it on Japan. Truman had to pick up and finish Roosevelt’s incomplete work. Legal scholar Cass Sunstein argues that Roosevelt’s political work is still left unfinished; in 2004 Sunstein published The Second Bill of Rights: FDR’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More than Ever.

In 1991 Shoumatoff published a memoir regarding her experience of painting “The Unfinished Portrait.” I plan on reading it soon.

I also found online a transcript of Robert G. Nixon’s oral history. He also has some interesting recollections of the day FDR died.

Wednesday, December 31st, 2008

J and I obviously didn’t plan on celebrating our anniversary apart from each other. I teased J that he was lucky to get out of planning an anniversary date. Instead, we sent each other e-cards that were decorated with art:

Jan Steen,

Love Sickness, c. 1660

Marc Chagall, Birthday, 1915

Marc Chagall, Birthday, 1915

Can you guess which person picked which painting?

During the 1660s, Steen painted several scenes of doctors paying house calls to visit female patients. As in this painting, Steen’s doctors usually do not recognize the cause of the female’s ailing health – love sickness. In some of Steen’s paintings that follow this theme, he also includes the phrase, “Here a physician is of no avail, since it is love sickness.” 1 I picked this card for J (yep, it was me!) because I literally got sick to my stomach when J returned home after a study abroad. We were close to getting engaged at that point; my doctor said I experienced too much “positive estress” with J’s return, which led to an excess of acid in my stomach. Now we joke that J gives me ulcers.

In this painting, it appears that this woman is estranged from her lover, as indicated by the letter in her hand. It wasn’t until after I sent J this painting that I realized it is especially appropriate for us today.

Chagall’s painting has a rather melancholy tone, since the woman is dressed in black clothes (perhaps funeral attire). It is thought by some that the woman is celebrating the birthday of a deceased lover; he floats above the woman and contorts his body so that he can give her a kiss. Although I suppose this seems like a morbid painting to send as an anniversary card, it is fitting in the sense that J and I are apart on our special day. Actually, the sentiment that J included with this card (did you guess that he’d pick a 20th century artist?!?) was quite fitting and lovely.

J also pointed out that Chagall’s floating figure is similar (in its awkward positioning and floating-ness) to some paintings by Brian Kershisnik. I don’t know why I didn’t notice that before: Kershisnik’s work is a little Chagallian, don’t you think?

1 Lyckle de Vries. “Steen, Jan.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, found online at http://www.oxfordartonline.com.erl.lib.byu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T081140, accessed December 31, 2008.

Wednesday, December 3rd, 2008

J just got an email from the Josef Albers Foundation. Apparently, the foundation is busy making a catalogue raisonne of all of the paintings by Albers. It looks like our Homage to the Square project won’t come to fruition, since the foundation is unlikely to sponsor or help with an additional project of a similar nature.

J just got an email from the Josef Albers Foundation. Apparently, the foundation is busy making a catalogue raisonne of all of the paintings by Albers. It looks like our Homage to the Square project won’t come to fruition, since the foundation is unlikely to sponsor or help with an additional project of a similar nature.

Sniff. Sniff.

I told J to look on the bright side – at least he was able to convince me to buy two rare, out-of-print books on Homage to the Square that I wouldn’t have been willing to purchase otherwise. And hey, at least a catalogue is being made…

Tuesday, October 28th, 2008

Last night after I turned out the light, J and I lay in bed and talked about art while we stared at the the ceiling. J recently came up with the fabulous idea to publish a book on the Homage to the Square series, and he asked me if I wanted to help. J’s going to do the design and I’m going to edit/write (although I’m sure J will have a lot of input for the essays too). At first, we thought that we would make a compilation of essays that have already been written on the series, but a preliminary search showed that there isn’t much written specifically on Homage to the Square. It looks like more people are interested in Albers’s life and work in the Bauhaus school. J and I wonder if this means that a) there aren’t enough interesting things to say about these squared exercises in color juxtapositions or b) the task of compiling and discussing these works is extremely daunting, given that Albers purportedly made a “seemingly endless number” of these squares over twenty-five years.1 We hope that people would have an interest in learning more about this series, and we’re willing to take the risk that the work might be daunting. It’s probably impossible to gather all of the series in one publication, but I would hope we could find a good collection.

Last night after I turned out the light, J and I lay in bed and talked about art while we stared at the the ceiling. J recently came up with the fabulous idea to publish a book on the Homage to the Square series, and he asked me if I wanted to help. J’s going to do the design and I’m going to edit/write (although I’m sure J will have a lot of input for the essays too). At first, we thought that we would make a compilation of essays that have already been written on the series, but a preliminary search showed that there isn’t much written specifically on Homage to the Square. It looks like more people are interested in Albers’s life and work in the Bauhaus school. J and I wonder if this means that a) there aren’t enough interesting things to say about these squared exercises in color juxtapositions or b) the task of compiling and discussing these works is extremely daunting, given that Albers purportedly made a “seemingly endless number” of these squares over twenty-five years.1 We hope that people would have an interest in learning more about this series, and we’re willing to take the risk that the work might be daunting. It’s probably impossible to gather all of the series in one publication, but I would hope we could find a good collection.

So, last night we stared at the ceiling and brainstormed some ideas of fun things to discuss in the book – perhaps the symbolism of the square or what the significance the square shape might have in regards to the Modernist movement. I’m also interested in examining how Albers’s observations in harmonious color arrangements tie into different color theories.

If there aren’t enough already-written essays to compile for a publication, we also brainstormed different people who we would “allow” to contribute to our book (Ha! As if we are at a point where we could pick and choose scholars, and do them a favor by accepting their submission). That being said, we’re definitely willing to look at any submissions or ideas that people have regarding the Homage to the Square series. Any thoughts?

Now we just need to find funding and a publisher for our great idea. Hmm.

1 H. H. Arnason, History of Modern Art, 1st ed., (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., 2004), 349.

Thursday, September 25th, 2008

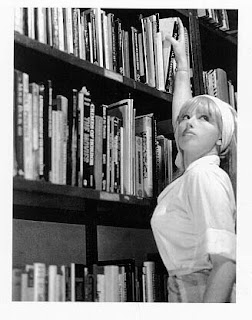

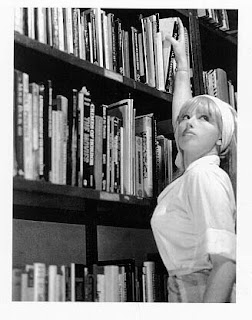

Quatorze asked me to do a post on Cindy Sherman, a photographer whose work I find very interesting. Beginning in the late 1970s, Sherman created a series of photographs which are reminiscent of Hollywood stills – however the “stills” are generic enough in setting and composition that they resist attribution to any specific film.

Quatorze asked me to do a post on Cindy Sherman, a photographer whose work I find very interesting. Beginning in the late 1970s, Sherman created a series of photographs which are reminiscent of Hollywood stills – however the “stills” are generic enough in setting and composition that they resist attribution to any specific film.

Sherman appears in her own photographs, often dressed in a wig and costume. She takes the photographs herself, using either a timer or a shutter release cable that she holds in her hand.

These photographs can be seen as a commentary on typical feminine post-war stereotypes of the 50s and 60s. Shown in opposition to the stereotypes that were encouraged by the (male) film industry during these decades, Sherman takes control of her image by chosing and creating her identity within the photograph. Therefore, although her image is still the object of the viewer’s gaze, Sherman is in control of her image and identity and not the viewer.

These photographs are (postmodernly) ambivalent, which has led to many different interpretations by feminists. While many find Sherman’s work to be in resistance to the male gaze and masculine order, others think that she is still working under the masculine construct of society.

These photographs are (postmodernly) ambivalent, which has led to many different interpretations by feminists. While many find Sherman’s work to be in resistance to the male gaze and masculine order, others think that she is still working under the masculine construct of society.

I can see valid reasoning for both arguments; my personal opinion of Sherman’s work relating to both male and female paradigms was reaffirmed when I learned that Sherman’s complete set of Untitled Film Stills was exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art (1997) under the sponsorship of Madonna. Yep, that’s right, the self-made sex symbol of the music industry sponsored the whole exhibition of a photographer who has been interpreted as resisting the male gaze! Given Madonna’s interest in Sherman’s work, it is obvious to see that her photographs are subject to multiple interpretations.

I find it completely fascinating that Madonna likes Cindy Sherman’s work. This image of Madonna and Cindy Sherman appeared in the Rolling Stone in 1997 (sorry for the poor reproduction – it’s a scan of a microfilm printout!). An interesting interpretation of the photograph appeared in this article in Afterimage, saying Sherman has experienced a role-reversal – instead of playing a starring role in the photograph (as she does in all of her own photographs), she is given second billing to the superstar Madonna. The article then continues to give an fascinating comparison and contrast of Madonna and Sherman, while also discussing the role that Sherman’s work plays in relation to media culture. One thing I found especially interesting was that Madonna is indebted to Sherman in some aspects – apparently many of Madonna’s photographs in Sex: Madonna look similar to Sherman’s film stills.

I find it completely fascinating that Madonna likes Cindy Sherman’s work. This image of Madonna and Cindy Sherman appeared in the Rolling Stone in 1997 (sorry for the poor reproduction – it’s a scan of a microfilm printout!). An interesting interpretation of the photograph appeared in this article in Afterimage, saying Sherman has experienced a role-reversal – instead of playing a starring role in the photograph (as she does in all of her own photographs), she is given second billing to the superstar Madonna. The article then continues to give an fascinating comparison and contrast of Madonna and Sherman, while also discussing the role that Sherman’s work plays in relation to media culture. One thing I found especially interesting was that Madonna is indebted to Sherman in some aspects – apparently many of Madonna’s photographs in Sex: Madonna look similar to Sherman’s film stills.

What do people think about this connection between Madonna and Cindy Sherman? For me, this reasserts that Sherman’s work really can be interpreted beyond a mere resistance of the male gaze. Plus, given Sherman’s interest in fashion (particularly outside of her film stills series), I can understand how she is interpreted as working within a masculine dominated society. But again, I can see her work being interpreted both ways. Just like the Untitled Film Series images resist attribution to a specific film, I guess that Sherman herself resists attribution to a single art interpretation.

Before Christmas, I worked on a project which involved scanning and transcribing the letters of a WWII soldier (Grandpa B) to his wife (Grandma B). It was a really fun project and gave me a nice break from unpacking and remodeling. J helped me transcribe some letters, including one that discussed Grandpa B’s reaction to Roosevelt’s sudden death. Both J and I knew that Roosevelt had died suddenly, but neither of us knew the details.

Before Christmas, I worked on a project which involved scanning and transcribing the letters of a WWII soldier (Grandpa B) to his wife (Grandma B). It was a really fun project and gave me a nice break from unpacking and remodeling. J helped me transcribe some letters, including one that discussed Grandpa B’s reaction to Roosevelt’s sudden death. Both J and I knew that Roosevelt had died suddenly, but neither of us knew the details.