Monday, July 29th, 2019

Queen Victoria’s Taste in Art

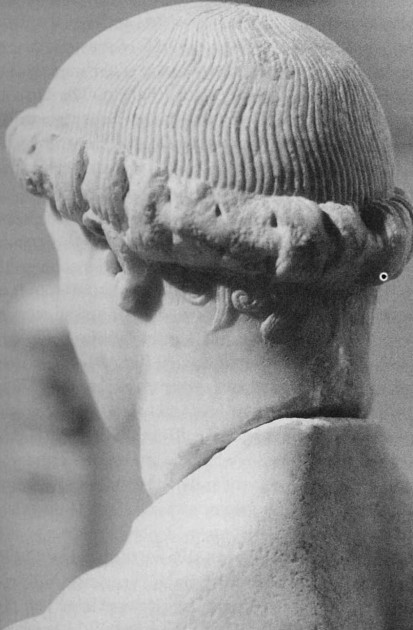

Franz Xaver Winterhalter, “Queen Victoria and Victoire, the Duchess of Nemours” (1852). Oil on canvas, 26.2″ x 20″, Royal Collection.

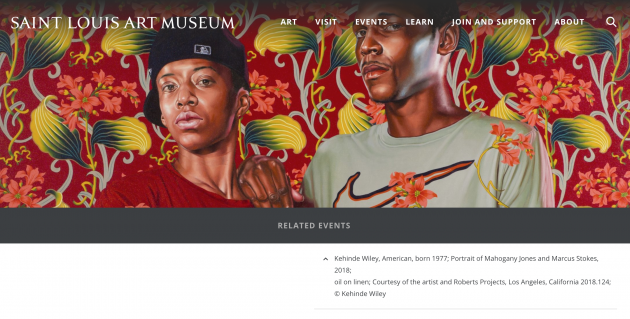

These past few months I have been delving into the art of the Pre-Raphaelites and William Morris, largely due to the Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts & Crafts Movement traveling exhibition that is in Seattle. I recently was asked what Queen Victoria, a supporter of the arts and an artist herself, would have thought of the Pre-Raphaelites. She definitely had an awareness of the movement (which I will discuss later), but her aesthetic preference seemed to veer more toward a more academic style, not only for public commissions but even private ones. Here are some of the contemporary painters whom she commissioned for portraits or purchased art from:

- Sir George Hayter was appointed principal painter to Queen Victoria and also drawing teacher for the princesses. Hayter painted Victoria in a portrait that was made between c. 1838-1840. He was knighted in 1842, and he also didn’t receive any royal commissions after this year as Victoria turned her interest to Winterhalter and Landseer’s paintings.

- Franz Xaver Winterhalter was one of Queen Victoria’s favorite painters. He made several official portraits for Queen Victoria, but he also made a private portrait (described as Albert’s favorite painting of his wife), and other portraits that included family members like her cousin, such as Queen Victoria and Victoire, the Duchess of Nemours (1852, shown above)

- Edwin Landseer also was commissioned to paint pictures of Victoria, her family members, and also her family pets. One such painting, Queen Victoria at Osborne, was commissioned to express and display her grief after Albert’s death. Landseer was so favored by Victoria that she even gave him a knighthood in 1850.

- Alfred Edward Chalon was commissioned to make a portrait of Queen Victoria, and she appointed him to be a watercolorist for the royal house. One of his images became used for stamps of the queen.

- Charles Robert Leslie painted an image of Queen Victoria in her coronation robes, and the queen said that she “like[d] the painting so much” that she bought it.

If you look at these art by these painters, particularly Winterhalter and Landseer (who both painted often for Victoria), it’s clear that she favored a traditional style of painting that included smoother brushstrokes and the color palette of the Academy (often, but not always, primary colors, which appropriately also fit with the red and blue colors of the Union Jack flag) .

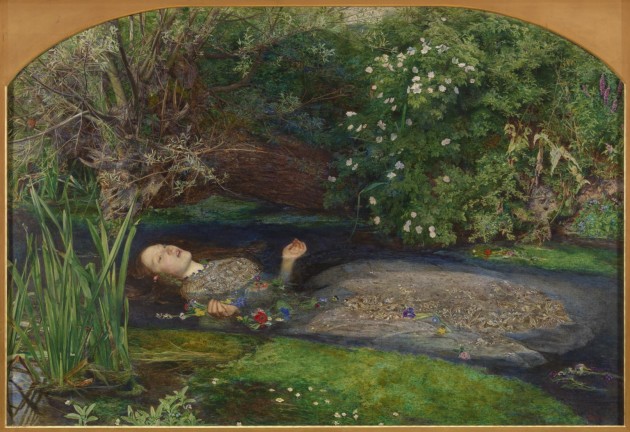

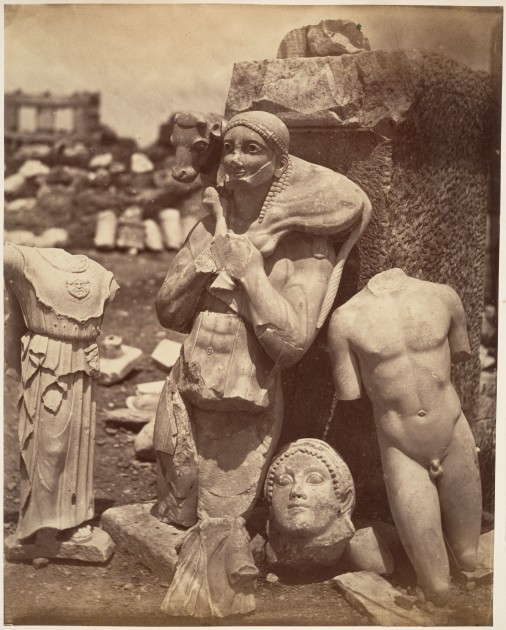

John Everett Millais, “Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter’s Shop),” 1849-50. Oil on Canvas, approx. 2.8′ x 4.5′. Tate Museum

She was aware of the artistic scene in England outside of her own royal artists, though, including news about the Pre-Raphaelites. When John Everett Millais’ painting “Christ in the House of His Parents” was exhibited in the Royal Academy show of 1850 and viciously attacked in the press, the Queen was so curious that she asked to have the painting brought from Trafalgar Square to the palace so she could see it herself.1 The news of the queen’s request was conveyed to Millais, and he in turn wrote to his friend William Holman Hunt, in perhaps a mix of both jest and sincerity, “I hope it will not have any bad effects on her mind.” I have read one account that the Queen applauded Millais for his efforts with this painting, but I haven’t found it substantiated by a primary source (does anyone know of one?).

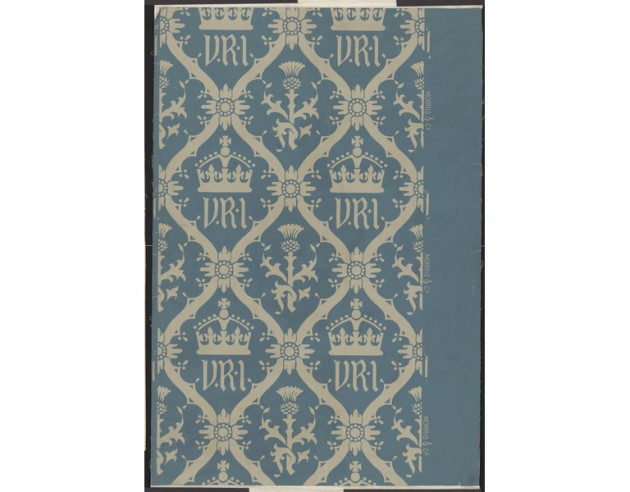

It is certain, however, that Queen Victoria did like the work of William Morris. In 1880, Morris created lavishly complex wallpaper for the Grand Staircase at Saint James’ Palace. Then in 1887, he was commissioned to create a unique wallpaper for Balmoral Castle which contained the cipher “VRI” (see example above). These projects helped to secure William Morris’ reputation and career.

Does anyone know of other instances in which Queen Victoria saw or commented on works of art by the Pre-Raphaelites (or William Morris, for that matter)? I know that the Queen prohibited Millais’ wife Effie from coming to court, due to her previous divorce from John Ruskin. Even when Millais received a baronetcy, Effie was banned from court. She was only received at an official function when Millais requested as much from the queen while on his deathbed.2 Interestingly, at some point her photograph also entered the Royal Collection, so now she keeps a continual presence with the royal family.

1 Charles Dickens was one of the critics who was appalled by this painting and its “loathsome minuteness” of style. He described the Christ child as ‘a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed gown’ and said that his mother Mary looked “so hideous in her ugliness that … she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest gin-shop in England” (Household Words, 15 June 1850).

2 The anecdote of Millais deathbed request (“Yes, let her receive my wife”) is recorded by Suzanne Fagence Cooper in “Effie: The Passionate Lives of Effie Gray, John Ruskin, and John Everett Millais,” p. 235-236. Found online here: https://books.google.com/books?id=vhlkCf-pbREC&lpg=PA236&ots=9deNRxw92x&dq=%22yes%20let%20her%20receive%20my%20wife%22&pg=PA235#v=onepage&q&f=false